The Architectural History of Egleston Square

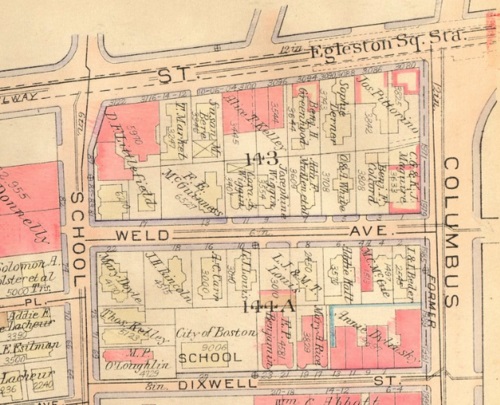

On November 16, 1848, a land surveyor acting on behalf of the Roxbury Latin School produced a plan of house lots and a new street on a sloping, 18-acre tract of land bounded by School Street, Washington Street, and Walnut Avenue (Norfolk County Deeds, Book 231, p. 19; Plan Book, 250, p. 77).

This was part of the largest bequest ever received by the school, founded in 1645, the oldest grammar school in Roxbury (including Jamaica Plain) and one of the oldest in British North America. At his death in 1672, the merchant Thomas Bell gave all his landed estate in Roxbury, where he had lived from 1635 until his return to England in late 1647, to the Roxbury Latin School. Bell’s home was on a hill overlooking Stony Brook near Amory and Boylston streets, where 179 Amory Street is today. Part of his land stretched from about Lamartine Street to Walnut Avenue. The town of Roxbury laid out School Street through his estate in January 1662, unnamed until 1825, when it was called School Street after the owner of the land.

For annual school operating income, the land was rented out to local farmers. Writing in 1847, Charles Ellis described the land as a “smooth open field on the brow of the hill with great apple orchards.” In 1848 the school looked to sell this parcel to increase its endowment. On December 3, 1848, the Boston merchant and real-estate broker Thomas Lord bought the 18-acre hillside tract. Lord lived on Pinckney Street at Beacon Hill but apparently moved to Roxbury in 1850, because in that year he joined Roxbury First Church and was a pew owner. This was about the time he completed his new home on the highest part of the property facing Walnut Avenue, and a three-acre parcel at the corner of School Street.

When Lord confirmed his deed and subdivision on September 15, 1853, presumably to pay off the mortgage, the document stated that it included a house and stable on Walnut Avenue and Seaver Street “or Egliston [sic] Square.” The property extended over to the “land of Aaron Davis Williams called Walnut Park.”

This is the earliest documented evidence of the name Egleston (or Egliston) Square, and it was apparently laid out at the expense of Thomas Lord, a very common practice by property owners who planned the subdivision of their land into house lots. Grenada Park (originally Byron Street) was built in 1848, probably by Lord.

On March 6, 1866 the Board of Selectmen of the town of West Roxbury voted to approve the petition of W.B.S. Gray and others to have "Eggleston [sic] square so called laid out and accepted as a town way,” indicating that this square had already been built. The selectmen went on to state, “The street has been found to be the requisite width and in good condition for public use…we have therefore laid out the street.” It was 48 feet wide and 900 feet long, and the cost was $2000. Walnut Park, probably built by A. D. Williams, was not accepted as a Roxbury town road until 1863.

Thomas Lord lived in his Walnut Avenue house first as a citizen of Roxbury, and after West Roxbury broke away in 1851, as a citizen of that town until his death in 1860. If there is a founder of Egleston Square, it is Thomas Lord. As late as 1874 his estate owned a small parcel on Washington Street next to the horsecar barn. The 1853 deed shows the property divided into house lots. The earliest houses built were numbers 38, 44, and 46 School Street, completed in 1851; all are still standing. Built by housewrights, number 38 is the most unusal. It is an L-shaped, gambrel-roof cottage built by Nathaniel Dorsey, a rare style for the time period. Three fine large mansions had been built in Egleston Square by 1873, one year before West Roxbury was annexed to the City of Boston. Lord’s house was bought about 1872 by Edward Rice, a dye stuff factory owner who remodeled it in the French style with a mansard roof in 1876. It was acquired by the Home for Aged Couples on May 1, 1887.

II. TRANSPORTATION

Lord’s estate fronted on Walnut Avenue, the oldest east-west road in Roxbury, connecting the town center with the farmlands and woodlands of the interior. It was originally called "the way to the great lotts and great meadows.” On May 2, 1638 the General Court granted 4000 acres to the town of Roxbury in order to establish the western boundary of Roxbury (founded in 1630) with Dedham (1636). The General Court stated that the lines of Roxbury would be eight miles from the meetinghouse (John Eliot Square). Until 1638 the border of Roxbury was located approximately at Walnut Avenue and Forest Hills Street (called Back Street because it was the back of the town). The 1638 ruling nearly doubled the size of Roxbury and brought within its precincts what is today Franklin Park and Forest Hills. More than likely a Native American trail, Walnut Avenue was surveyed and measured in 1663 as a town road maintained by adjacent property owners.

In early 1806, the Norfolk & Bristol Turnpike opened for business – a 35-mile-long toll road from Bartlett Street in Roxbury to Providence, Rhode Island. Government of that time did not pay for public works; only a privately incorporated turnpike corporation could support that type of highway, and it was authorized by the General Court in 1803. Three of the incorporators were William Heath, Thomas Williams and John Williams. The Williamses owned great tracts of land, parts of which are today Franklin Park. The Williams family also owned land from Boylston Street to School Street, and back to Amory Street.

The corporation was capitalized at $192,000 and construction barely came in on budget; the total cost for the 24-foot-wide gravel road was $191,168. The first tollhouse outside Roxbury was at the crossroads of South Street and Walnut Avenue, and the neighborhood quickly took the name Tollgate, which later changed to Forest Hills. On July 11, 1835 the Boston & Providence Railroad began service from Park Square to Providence, Rhode Island, a distance of 44 miles; some of it paralleled the toll road. The turnpike could not compete, and the Roxbury-to-Dedham section of the road became a free public road in 1857. In June of 1874 the turnpike from Roxbury through Dedham and Norwood was named Washington Street.

The end of the Norfolk & Bristol Turnpike made it possible for another mode of transportation to use the well-made highway, built of gravel six inches thick, with drainage ditches on each side. This was the horse railway.

The development of fixed rails as a means for smoother and faster transportation was a merger of the railroad and the omnibus, the urban stagecoach pulled by horses that began operating through Boston in 1829. By putting the popular omnibus on steel wheels, rolling on smooth level rails along a public street, it allowed two horses to pull 24 passengers comfortably.

On May 21, 1853, the Metropolitan Street Railroad Company (MRCo) was chartered to run horsecars from Boston to Roxbury. Service began in 1856, starting at the Boylston Market on Washington and Essex streets and running over the Neck to Norfolk House in John Eliot Square. The line was extended to Egleston Square along the Norfolk & Bristol Turnpike right-of-way in 1858, and to Forest Hills in 1864. The fare was ten cents, and the route to Egleston Square was called the Roxbury Hourly for the time it took to travel. Cars left the Boylston Market every two minutes. Sleighs were used when the company was unable to plow the snow off the tracks.

In its issue of April 25, 1857 Ballou’s Pictorial predicted the future of the growth of the city and Egleston Square: “The horsecars are still a novelty in our streets and attract great attention as they pass and repass. They are indicators of the change that is constantly taking place in our midst.”

Change took place at Egleston Square on August 6, 1867, when the MRCo bought a 20,500 square-foot, corner lot at School Street and Washington Street for $3000, and built two wood-frame streetcar barns. A brick addition was added later for horses (streetcar yards were notorious firetraps with flammable hay and feed). The average car barn was 125 feet long and capable of holding 28 cars. The second story of the brick building had accommodations for all repair shops. From its earliest years, MRCo did as much of its own work as possible. In its 1857 annual report it stated that “all repairs to cars, horse shoeing, harness making, paint shops, blacksmith and foundry are done by the company.” There was even a generator for grinding grain.

The total number of horses owned by the company in 1857 was 590, with 63 cars, or nine horses for each car. Thirty years later the company had 3,502 horses and 721 streetcars. The French Percheron horse – first imported to the United States in 1851 – was the animal preferred by streetcar operators because of its strength and size. Boston had many of them on the car lines. During the Civil War, when horses were in short supply, mules were used to pull city streetcars, although this cannot be documented for Boston.

On February 5, 1884, a Boston Globe reporter sat down with Mr. Charles Cook, who was in charge of the Grove Hall stable. His description of the draft horses used on street railways could be comparable to those used at the Egleston car house:

“Most of our horses come from the north and west. It takes about a year to harden them up, become acclimated and get used to the work ... Five years is considered a fair average a horse can be used for service ... The average amount of travel time by each horse daily is about 14 miles. When they have been in service for some years and are no longer suited for our purpose we sell them to farmers and peddlers for slow work. ... At present I have 400 horses under my charge. I have 25 hostlers, 5 blacksmiths, 4 feeders and 2 harness makers.”

MRCo, like other horsecar lines, departed at frequent intervals to lessen overcrowding, which could injure or even kill a horse. Stops were also spread out at specific street corners to avoid too many stops and starts that could harm horses’ legs.

III. INSTITUTIONS

West Roxbury overwhelmingly voted to be annexed to the City of Boston on October 7, 1877. By that time a tidy village had grown up of 58 two-story, wood-frame, hipped-roof houses from Weld Avenue to Arcadia Street. Some were duplex houses, and most are still standing today. The community was large enough to support its first church; on June 13, 1872 the Methodist Episcopal Church was dedicated at the corner of Beethoven and Washington streets. It was a wood-frame, Ruskinian Gothic style with steep slate roof. After the elevated trestle was built in 1909, the church moved to a house at the quieter corner of Walnut Street and Walnut Avenue. In 1911 it was sold to the Swedish Methodist Episcopal Church, which worshipped for about 40 years. The site was a vacant lot by 1962. During the Washington Park Urban Renewal, the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) designed a small playground on the site in 1964. The Walnut Avenue playground was completely redesigned by Wallace Floyd Associates, and rebuilt in 1992.

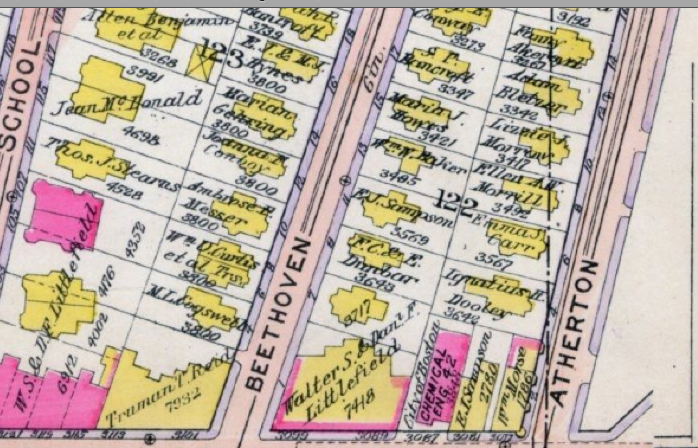

Two years after the MRCo opened its horsecar barns, George Cox bought two acres of land between School Street, the newly-built Egleston Square, and Washington Street, part of the Lord estate, on September 8, 1869, for $13,639. Predicting the increase in population due to improved fixed-rail transportation, Cox had the land subdivided into thirty house lots. Twenty-one houses were sold in the first year, and Cox built Weld Avenue at his own expense in 1871 to connect the new homes. (Numbers 1-3, 6, 9 and 11 Weld Avenue still stand.) By the end of 1872, Cox had sold 58 homes on Weld Avenue, School and Washington streets, Beethoven and Atherton streets. The latter two streets were built by Cox in 1869. Beethoven Street is today an intact street of homes built on Cox land between 1870 and 1872. Cox built Atherton Street as far as Arcadia. All streets were accepted as City streets in 1874 after annexation.

Until the first decade of the 20th century, the hillsides of School Street and Walnut Park would be dotted with large estates and big houses. Two of the largest were built by Frederick Howard and Charles Clapp.

After annexation the city began to expand its school system. In 1881, the three-story, robust panel-brick building named the George Putnam School opened in Egleston Square (Columbus Avenue). Built and probably designed by Griffin & O’Sullivan contractors, it was located on the estate of Thomas Littlefield, which faced the square. Named after George Putnam, the pastor of Roxbury First Church who died in 1878, the school was razed by 1962. The original stone wall of the estate is still in place.

Other city services followed in the new community. Egleston Square Firehouse, Engine 5 was built about 1880 next to the Methodist Episcopal Church. A new firehouse designed by Robert Cutler on Columbus Avenue and Bragdon Street, below Dimock Health Center, was dedicated on December 19, 1952. The old fire station was razed for the municipal parking lot that still serves the business district.

Also established in Egleston Square were two institutions built by and for women: the New England Hospital for Women and Children, incorporated on March 12, 1863, and the sixteen-acre Sisters of Notre Dame Academy, which opened on May 1, 1859. The Archdiocese of Boston bought sixteen acres on a hillside overlooking Washington Street in June 1853, for the purpose of establishing a boarding school for girls who would be educated by the Notre Dame Order to be teachers for the parochial schools of the diocese. The large, four-story, panel-brick building with central cupola was designed by Patrick C. Keely. Sister Helen Ingraham from Framingham, a1905 graduate, became the first president of Emmanuel College, established in the Fenway by the Sisters of Notre Dame in 1919, as the first Catholic women's college in New England. The Sisters of Notre Dame Academy moved to Hingham in 1961, and the BRA bought the campus on May 16, 1963 to build the Academy Homes housing project.

The New England Hospital for Women and Children, today known as the Dimock Community Health Center, is named for Dr. Susan Dimock (1847-1875), America’s first female resident surgeon. Denied access to male-dominated medical schools, two women (Dr. Marie Zakrzewska and Ellen Dow Cheney) founded their own teaching hospital in 1863. It was first located on Pleasant Street outside Park Square, and moved to the spacious ten-acre campus outside Egleston Square in 1872. The first two buildings, both designed by Cummings & Sears, were Cary Cottage in 1872 and the Marie Zakrzewska Medical Building in 1873. The Medical Building was an imposing, red-brick Gothic building with three-story stick-style verandas and tall turrets visible from Columbus Avenue. It won an award at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition. Over 58 years four other buildings – a third by Cummings & Sears (the Cheney Surgical Building in 1899) – would be added, giving the campus an air of grandeur.

In 1992 the Ruth Batson Youth and Family Center opened at 1800 Columbus Avenue, behind the fire station. Designed by August Associates, it was named for one of the co-founders of METCO that long had its headquarters at Dimock. Codman Avenue, a privately-built road through the estate of Henry Codman, connected the hospital with Washington Street; it was rebuilt by the city of Boston in 1884 and renamed Dimock Street.

The third institution established in Egleston Square was the Home for Aged Couples at 419 Walnut Avenue. It was incorporated on May 20, 1884 at 431 Shawmut Avenue, as the New England Aid Society for the Aged and Friendless. On May 1, 1887 it bought the three-acre Rice estate at Walnut Avenue and School Street, changed its name, and added five buildings to the property. The first was built in 1893 at the School Street corner, and was designed by John A. Fox (who also designed two buildings at Dimock). In 1910 the Lord/Rice house was razed and the present Badger Building built, also designed by Fox.

In 1929, Shepley Rutan & Coolidge designed the distinctive resident home with Flemish end- walls at 2061-2055 Columbus Avenue. Two other housing wings, with a total of 83 apartments, were added in 2007 and 2017: Spencer House and Franklin Park Place, designed by Chia Ming Sze. The former Home for Aged Couples today is owned and managed by Rogerson Communities as housing for low- and moderate-income seniors and supportive services.

IV. THE FIRST BUSINESS DISTRICT

The village of Egleston Square also had a small business district with an urban style of housing over commercial stores. Number 3118-3122 Washington Street – a wood-frame, two-story building built by George Cox – had probably the earliest retail store in the Square. Of course the earliest business was collecting horse manure from the streets and selling it to local house gardens and farms. This was done by children and adults with a tip cart or wagon. The MRCo had a volume monopoly on this because stablemen cleaned out the stalls and sold the manure to farms.

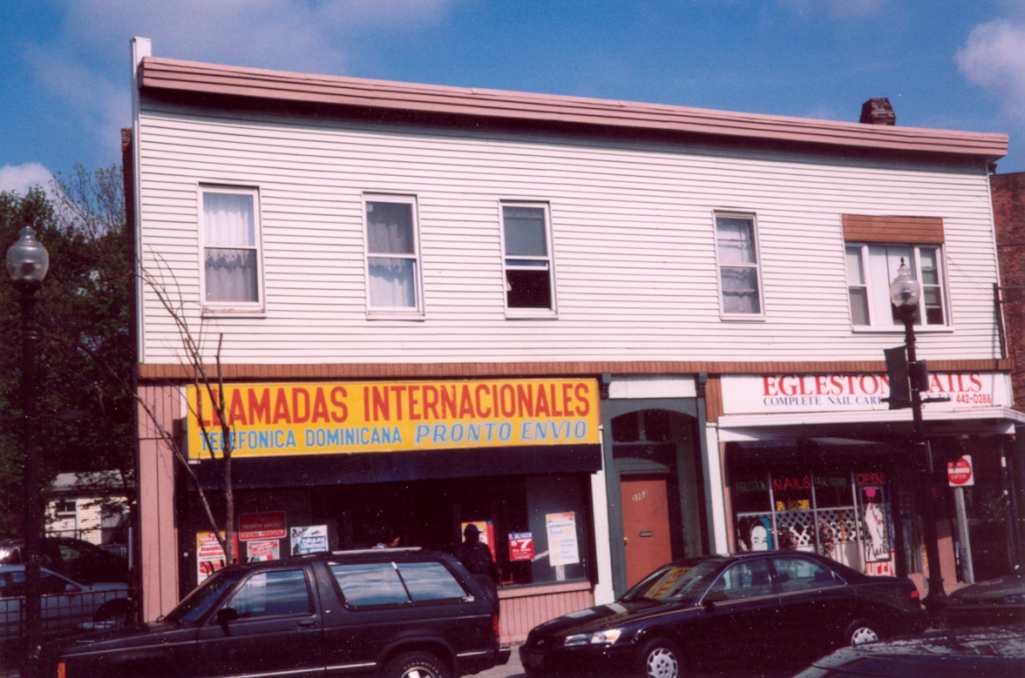

The earliest documented housing over retail is the Kittredge Block at 3103-3113 Washington Street, developed by Francis W. Kittredge (who had a home in Egleston Square). Kittredge was a Justice of the Peace, and on May 5, 1870 bought two parcels from George Cox. In 1882 Kittredge hired Waite & Cutler to design and build a long, two-story, wood-frame building with two ground-floor stores and apartments above. It was permitted on May 19, 1882, and was open for business in a year. For many years Egleston Hardware was in one storefront, but that half was removed about 1988 and is now a city parking lot. One of the stores certainly included a post office counter for money orders and mail pickup-and-delivery.

Until cut off by the extension of Columbus Avenue in 1895, the largest business in the Square was the Herman Grundel Nursery at Atherton and Washington streets. Built by 1874, Grundel grew vegetables for the local Egleston market, and was no doubt a customer for the manure from the MRCo stable. He lived in a house adjacent to his greenhouses.

V. FRANKLIN PARK

The eastern end of Egleston Square at Walnut Avenue became one of the boundaries of Franklin Park when landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted proposed that a tract of land, 500 acres across, be set aside for Boston’s central park. Land takings began in 1880; thirty-nine acres were acquired along Walnut Avenue in 1884 that included the steep, jagged Roxbury conglomerate cliffs above Seaver Street. That was the first section of the park completed, a thirty-acre space Olmsted called the Playstead, designed for active recreation. Olmsted was well aware of the growing popularity of sports in American life, and with the Playstead he provided the first urban park with a planned recreation area. The topography was ideal, flat but very rocky. Those boulders were used to make an 800-foot long viewing platform, called the Overlook, on the shady western edge of the grounds. Olmsted also noticed that a thickly-settled residential center was growing up right along the Walnut Avenue boundary of the park with reliable mass transit.

Construction began in the summer of 1885 and the Playstead was opened for schoolboy sports on June 13, 1889. All Boston school children – many no doubt from the Putnam School – were given the day off, and free streetcar service provided to the opening-day ceremonies with a flag raising. The Boston Evening Transcript was enthusiastic about the opening in its June 5, 1889 issue: “The playground of our new and magnificent park may exercise a lost important function in our history ... when it is all completed we shall have when in Franklin Park a pleasure ground unrivalled in the whole world in beauty.”

The Walnut Avenue entrance opposite School Street was planned as the carriage gateway to the park from Egleston Square; the Sigourney Street entrance was a gate to the Playstead. At this point Walnut Avenue historically turned and followed a route through fields out to South Street and later Morton Street, but it was discontinued 1000 feet from School Street. Old Walnut Avenue – with little change other than building curbs and regrading – became part of Circuit Drive, the main roadway around Franklin Park. Capitalizing on the planned new park, George Bond laid out Sigourney Street through his property – on which he was building large homes – in 1884. Numbers 26 and 32 Sigourney Street were built at this time.

The Walnut Avenue entrance was designed in October 1888. The long rocky ridge above Seaver Street was known since the 17th century as the Long Crouch, and Olmsted – as was his custom in recalling old place names in Franklin Park – named it Long Crouch Woods. A walking path with lights was built in 1894 through the center of the woods, and in 1906 steps were built into the wall along Walnut Avenue as the Egleston Square foot entrance to the park. The bear dens, designed by Arthur Shurcliff as part of his master plan for the Franklin Park Zoo, were completed in 1912 at the center of Long Crouch Woods, tucked into its highest ridge. These were closed and abandoned in 1970, although there are still the architectural remnants of the enclosures there.

In February 1947 Park Commissioner William Long, then living on Tower Street in Forest Hills, received petitions from community groups for a sports stadium. The petitions worked; on September 7, 1947 Desmond & Lord architects were engaged to design a stadium in the Playstead that would line up with the Walnut Avenue entrance and the Egleston Square elevated station. The $1.250 million White Stadium opened with appropriate ceremonies on September 28, 1949, named after George Robert White, who on his death in 1922 gave $5 million to Boston for public benefit. Egleston Square and other neighborhood youngsters resented the stadium because it took away their baseball fields; the stadium took up over half the Playstead. Today it has two baseball diamonds, a cricket pitch and basketball nets in the unused parking lot.

VI. ELECTRIFIED STREECARS

In 1886 Henry M. Whitney had a problem. He had organized the West End Street Railway to bring transportation to his new housing developments on Beacon Street near Brookline. The problem was that horses could not pull the cars up the hill to Coolidge Corner. In 1887, Whitney’s West End Street Railway gained control of the Metropolitan railway and four other street railways to become the first company to provide uniform public transit. Whitney began looking at an alternative to horsepower, and after seeing electric cars in Pittsburgh and Washington DC, he converted his line to electric power on January 1, 1889.

He purchased land on Albany Street and Harrison Avenue convenient to the coal docks on Fort Point Channel and built a central power station equal to 2000 horses in engines and boilers. The conversion to electric service required building catenary wire poles, setting heavier rails, and the conversion and enlargement of the old horsecars until new ones could be purchased. The electric cars were very colorful for the first twenty years: two-tone red-on-dark-blue or green-on-brown with silver letters. In 1909, all surface cars were painted green with white trim.

The first electric cars ran on the Egleston Square line on September 1, 1890. As reported in the Boston Globe of August 28, 1890: "[Electrics] will run between Tremont House, Egleston Square and Forest Hills with stops at Dudley Street ... There will be half hour electric service from Tremont House to Dudley Street." There were 160 trips daily to Egleston Square, and a new schedule was put into effect of 270 trips a day. Cars would leave every five minutes from Egleston Square.

VII. THE FIRST APARTMENT HOUSES

On July 26, 1894 the Boston Globe reported about a new housing phenomenon: “There seems to be a good demand for tenements in Roxbury… many large plots are being opened up for builders of apartment houses.” It marked an era of change, as the Globe reported on October 14, 1894: “These new style houses are successful from both a financial and practical standpoint." Population was growing and street transit becoming modernized.

The first two apartment buildings in Egleston Square – still today the most dominant architectural features of the square – were developed by property owners Daniel and Walter Littlefield who lived on Egleston Square near Weld Avenue (they sold half their land to the City of Boston about 1879 for the Putnam School). Both apartment houses were four-story brick buildings with ground-floor stores on opposite corners of School and Washington streets, creating an entrance to the square. One was built on vacant land and the other replaced a Cox-built building.

The building at 3125 Washington Street was the first apartment building in Egleston Square – and one of the earliest in Jamaica Plain and Roxbury – built in 1893. It was designed and probably built by J. F. and J. S. Smith, originally with six apartments and two stores next to the 1882 Kittredge Block. In 1900 the stores were connected together for a market and the building changed to twelve apartments.

Behind this building the Littlefields built a wood-frame duplex at 101 School Street by 1890. It has a hip roof with distinctive scroll bracket porch. In 1905 they hired Frank Sawyer to design a six-family, brick duplex apartment building next door at number 107, called the Georgian, completed in April 1905. By then the Littlefields – who were in the fruit-and-produce business – lived at 35 Hutchings Street. The Littlefields hired the notable architect Cornelius Russell to design the handsome, corner apartment house at 3118-3122 Washington Street, replacing a Cox building which had one of the first ground-floor stores. The Russell building was completed in December 1897 for $40,000. It also had a doorway at 87 School Street. It was built for thirteen families and two stores. The stores were later connected for a First National grocery store that occupied the corner well into the 1950s. Stop & Shop opened in 1953 at 315 Centre Street next to the Plant Shoe Factory, with an ample parking lot, an amenity Egleston Square businesses lacked. It proved tough competition for First National as well as the nearby A & P store, and both closed in the early 1960s.

In 1896 Nathan Fitts bought the Ezra Farnsworth House and stable at 48-54 School Street (ca. 1873) and erected the third apartment building in the square. Designed by William Holmes, it consists of four attached, three-family buildings built in yellow brick with pressed-metal bays and distinctive Venetian windows. Completed in 1897, it included a corner store.

On the outskirts of Egleston Square, George Allen created a different style of housing at 2991-3003 at the corner of Bragdon Street. Capitalizing no doubt on the presence of the New England Hospital for Women and its work force, Allen subdivided a parcel of land along Washington Street and laid out 43 house lots on two new streets, Notre Dame and Bragdon, in April 1871. He built a few wood-frame houses on Notre Dame Street (some of which still stand).

On the Bragdon/Washington Street corner on a 16,000 square-foot lot, he built something new: a series of four, three-story, double row-houses with mansard roofs and high stoops, all built by 1873. These houses were sold individually; building permits do not now exist, but in 1900 each building had four apartments. A seemingly uniform block of high-shouldered buildings, a closer look reveals each building is slightly different, suggesting they were built by different architect/builders. Number 3003 is a panel-brick design; others have different entrances and slightly different curves of the roofline. A curious detail is that the end wall of 3003 is a blank wall without any finishing details (making it perfect for billboards which may have been the intention).

Allen’s development was the first housing development outside Egleston Square towards Dudley Square and the first and last large-scale development in the South End style row-house in Egleston Square. Beyond the Allen block development would all be wood-frame, 2½-story, pitch-roof, streetcar-suburb housing as far as Guild Street.

For years after annexation, the City of Boston proposed a street that would connect Amory Street with West Walnut Park called Brunswick Street. In 1895 the City public works department went even further; it extended Columbus Avenue from its terminus near the railyards at Northampton Street in a straight line through the 1866 Egleston Square to Seaver Street. This changed Egleston Square to a crossroads. Columbus Avenue opened up a huge area for growth with large lots on a main street. The new avenue also took Grundel’s house and cut his nursery grounds in half, also cutting diagonally through the land owned by Christopher Spenceley since at least 1873. Spenceley lost no time capitalizing on this public improvement. In July 1898 he hired the architect/builder Patrick J. Tracy to design a distinctive yellow-brick, flatiron-type building with heavy overhanging cornice, six metal bays and arched doorways with inset steps. Numbered 1899 and 1913 Columbus Avenue, it was planned as six, three-family buildings with a corner store. Below the cornice at the West Walnut Park nose of the building above the store is a limestone plaque reading “CJ Spenceley Block. 1898.” The end wall of number 1899 is solid brick, indicating that a future apartment building would be built on the corner with Bray Street.

About the same time, four wood-frame buildings with bow fronts and bay windows were built at the corner of Atherton Street. These were clearly low-rent tenements. The ground floor had three stores, one of which (after World War II) was the Egleston Tavern. In dilapidated condition, and taken by the City, two of the buildings were razed about 1980; only the building numbered 1955-1957 Columbus Avenue remains of this block next to the used car lot. Egleston Plaza was built on the site about 1990. The fourth building built next to the firehouse also had a ground-floor store. It was razed about 1988 and is today a small shady park with a bike rental rack.

In 1902, William H. Smith completed a group of sixteen, three-family apartment buildings at 2031-2041 Columbus Avenue, and 6-16 Cleaves Street (renamed Cleaves Court about 1971). Designed by James Booth, the two Columbus Avenue rows were built of yellow brick with broad metal cornices and round arch entrances with inset stairs. The parallel rows on Cleaves Court were built of red brick. This marks the earliest subdivision of an entire estate, that of Thomas Robison, who built his home about 1869. When Columbus Avenue was extended to Walnut Avenue, this provided direct transit access to the downtown.

The Cleaves Court buildings form a tidy, shady courtyard of 66 flats. It was built almost exactly on the site of the Robinson house. The building permits were lost during a major renovation in 1969-1971 by the emerging black architect Don Stull. At that time it was renamed Cleaves Court, with a new balcony and stairs. The cornices were removed during that renovation. In 1971 the first and (to date) last piece of public art in Egleston Square was commissioned by the Cleaves Court developers for the redesigned courtyard: a metal abstract sculpture done by George Greenamayer, who taught at Mass College of Art, erected in 1973.

The Roxbury ward boss Timothy Connolly and his son built many brick row houses for Irish immigrants in the late 1880s through the 1890s, in lower Roxbury and the South End, near the Albany Street lumber and coal wharfs. In 1899 he developed and built at 2985-2987 Washington Street a long, broad-faced, yellow-brick apartment building with twin bay windows, for four families and two stores

VIII. THE ELEVATED

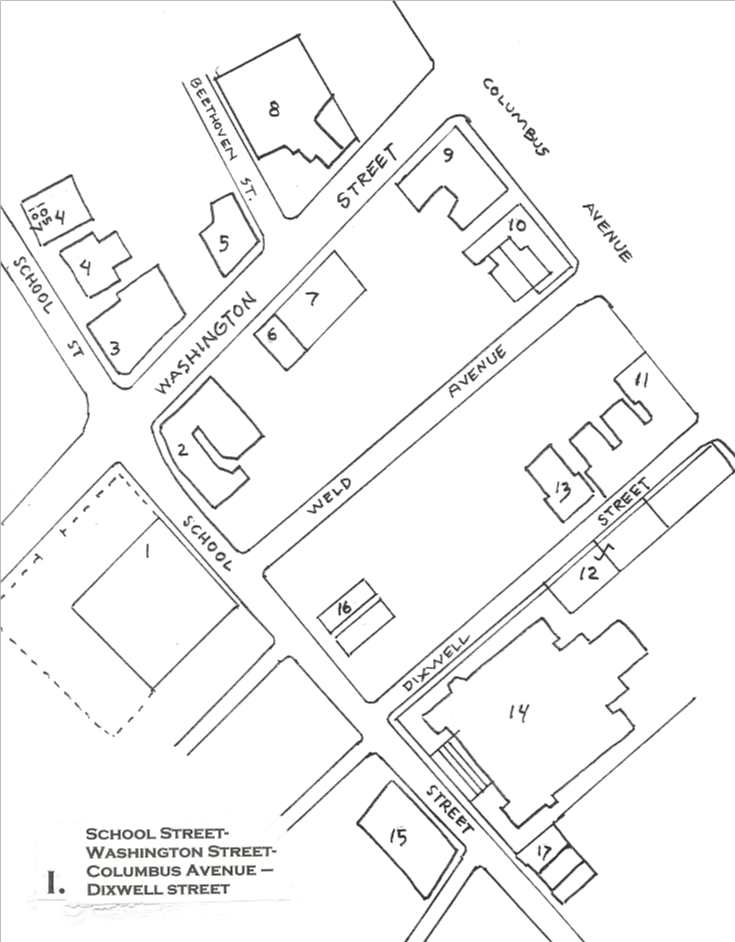

Egleston Square became a transit hub on November 22, 1909, when elevated rapid-transit service began from Dudley Terminal to Forest Hills; it would remain a transportation center for 78 years. Egleston Square station was planned as a transfer place for streetcars coming from Dorchester and Mattapan. It was the first station in which platforms, galleries, and stair landings were designed of reinforced concrete. The 350-foot-long platform was built to accommodate eight car trains and a waiting room, suspended over the junction of Washington Street and Columbus Avenue on four steel beams over fifteen feet above that crossroads. These beams, or bents, were set in concrete boxes deep below the street and supported double tracks; from bottom to waiting room top the elevated station was about forty-eight feet high. George A. Kimbal was the chief engineer and Robert S. Peabody the architect.

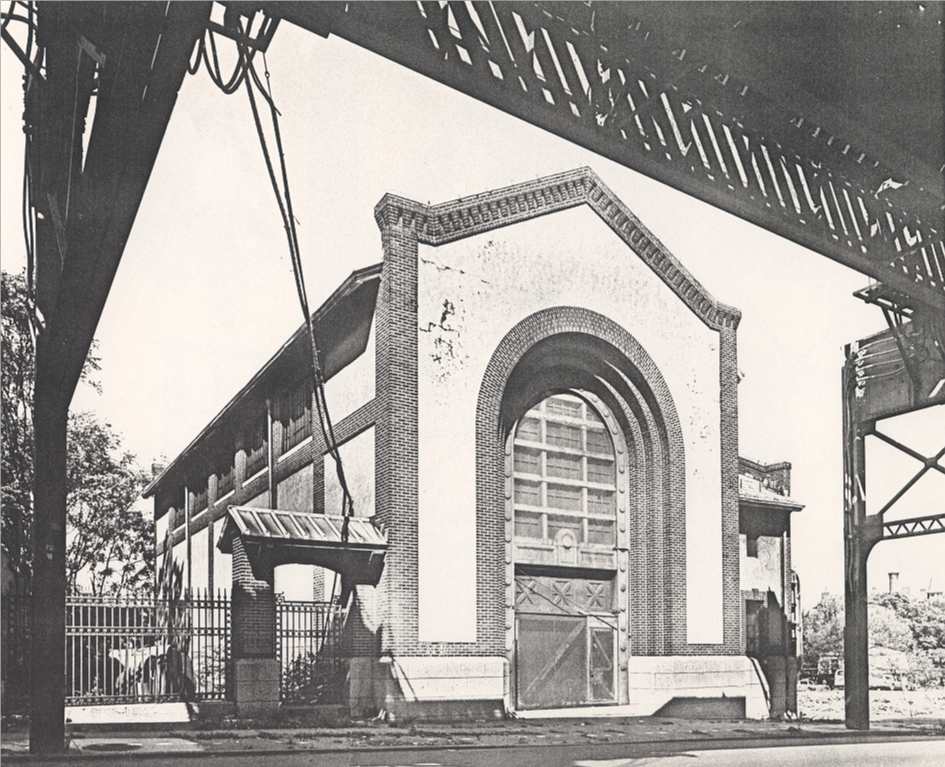

Peabody designed a power station on Washington Street to provide alternative current to the rapid transit line. The building was built on two parcels of Codman family land at the corner of Bray Street. Completed in 1909, it resembled a Roman basilica: a tall, brick-and-stucco building with an elegant recessed arch trimmed in brick. Vacant for eighteen years, it was acquired by Urban Edge from the MBTA on June 7, 2005 for $560,000. While it originally held four giant dynamos, it was completely gutted and rebuilt for the Neighborhood Network cable access station by Scott Payette, architect. The new cable television station opened on April 12, 2008. The adaptive reuse cost over $8 million.

The extension of Columbus Avenue was built with tracks and catenary poles, and the increase in transit routes necessitated more space than the School Street car barns provided, so land was leased at Columbus and Washington streets for a streetcar turnaround and layover yard with waiting platforms. This ¾ acre parcel was leased by the West End Street railway by about 1900. The corner had originally been the Frederick Howard estate of about two acres, with his house facing Walnut Park, suggesting it was built about 1864. The estate had been subdivided by 1889. When the West End Company leased it, the land was used as a nursery, probably for Grundels, which had been displaced by the Columbus Avenue extension. In 1916, the Boston Elevated Company bought the land and built a new surface car station on the site with connecting overhead passageway to the elevated platforms; it opened on January 20, 1917. This would be the transfer station for the heavily-used Egleston-to-Mattapan streetcar, the “back-and-forth line" between Forest Hills and Egleston and the main line down Columbus Avenue, connecting with the subway at Copley Square.

In the fall of 1916 a streetcar reservation was built down Seaver Street. Streetcars coming out of the station would travel in the center of old Egleston Square before shifting to the shoulder of Franklin Park, in a reservation that extended to Blue Hill Avenue. At Blue Hill Avenue, streetcars ran in a reservation in the middle of that boulevard. When buses replaced electric streetcars in 1955, Seaver Street was widened as a four-lane, divided road with a median strip.

IX. THE NEW BUSINESS DISTRICT

The elevated line changed the business district. The two-story, wood-frame houses with ground-floor stores on stepped-up galleries, were replaced by the strip storefront buildings. The first was built by the Highland Businessmen Association at 3104-3096 Washington Street. A duplex, wood-frame house from about 1871 was razed, and a one-story grocery and restaurant was built (permitted in May 1908). A. J. Carpenter was the architect. In May 1948 it was combined into one store.

Number 3096 Washington Street was built next to a three-story, wood-frame, flat-roof building built about 1900 (or before 1905). This is number 3106 Washington Street, and is unique in the business district: a two-story, residential building over two ground-floor, street-level stores. Number 3106 replaced an older house that had a large, hip-roofed stable in the rear. This suggests two things: it was built as a rental stable for the horses and carriages, or the merchant made deliveries with a box wagon and team.

Numbers 3092-3094 Washington Street were two Cox-built houses converted into two stores in 1915 (permit October 21, 1915). A twelve-foot brick addition was built out to the sidewalk. The houses were torn down in May 1929 by the owner, Charles Lerner, and he hired Gustave W. Priesing of Roxbury Crossing to design three stores of brick-and-cast-stone, completed in late 1929.

On Columbus Avenue and Weld Avenue, C. G. Maguire Realty built a long, brick commercial block around a two-story, wood-frame, hip-roof, Cox-built house on Weld Avenue. Samuel S. Levy designed this, completed on December 5, 1917. Today (2017) it contains four stores, including Skippy White's Records at 1971 Columbus Avenue.

At the Washington Street corner, two wood-frame houses were removed in July 1925 and a new storefront built, designed by John Halferstein, completed in late 1925. This building is number 3080 Washington Street and 1986-1987 Columbus Avenue. After World War II, the Columbus Avenue stores were occupied by Columbus Taxi and Egleston Delicatessen.

Tillie Markel, of 22 Westminster Avenue, owned 3112-3114 Washington Street, a two-story, wood-frame house and store with a slate roof. Merkel hired architect S. S. Eisenberg to remodel the building and add a third store in May 1924. Condemned by the City in 1941 and razed, a new cinder-block store 43 feet long was built in its place, designed by Herman L Freer.

The building at 3093-3095 Washington Street was built about 1910, after the Methodist Episcopal Church moved to quieter quarters. Daniel and Walter Littlefield bought and razed the church, and in its place built a one-story brick block of stores on the whole 14,700 square-foot lot from Beethoven Street to the firehouse. In 1925, the Littlefield brothers hired architects Densmore, LeClear and Robbins to design the Egleston Square Theater. The box office and lobby were built in the center of the storefronts; the theater rose up behind the stores. For many years Lodgens Market occupied one of the stores; today it is La Paraviana Market. The first film was shown in the theatre on May 1, 1926. It closed in April 1961. Vacant for over forty years, it was razed in the summer of 2003 for housing.

Two new churches came to Egleston Sqaure at the turn of the 20th century, reflecting not only the changing demographics but population growth. On January 4, 1900 the German Methodist Episcopal Church at 169 Amory Street was dedicated with two services, one in German and the other English. The church on Amory Street at the corner of Atherton was a straight line from Egleston Square. Designed by Jacob Luippold, the church was organized in 1853 and met for over forty years at Williams and Washington streets.

St. Mary of the Angels Church celebrated its first mass on May 26, 1906 in the old West End Street Railway car barn. The church was carved out of St. Joseph's Church parish on Washington and Circuit streets outside Dudley Square (razed in 2003). Father Henry Barry, the founder of St. Mary's of the Angels, wanted a new church. He bought the Schuman house (built about 1865) in the summer of 1906, on the corner lot of Seaver Street and Walnut Avenue. In 1907, he hired the noted architect Edward T. P. Graham to design a stone Gothic church with a central, crenellated parapet tower. A photograph of the planned church was published in the Boston Herald of October 6, 1907. The basement section of the church was completed on March 8, 1908 and the first mass celebrated soon after, a common practice for many churches until funds were raised to complete the building. But plans were abandoned in the 1930s as the Catholic population declined and the parish became more Jewish. St. Mary’s parishioners have worshipped in the lower church ever since. A low, gable-truss roof was built in 1987 to replace the original flat roof. The Schuman house has long served as rectory, living quarters, and community center for the parish and Egleston Square. In 2004, St. Mary of the Angels Church successfully fought off the attempt of the Archdiocese to close it, making the case that it was an essential part of the Egleston Square community. Archbishop Sean O’Malley celebrated the centennial of St. Mary of the Angels on September 10, 2006.

Two side streets off the business district connect Washington Street with Amory Street, West Walnut Park and Atherton Street. West Walnut Park was built to Bancroft Street in 1877, and extended to Amory Street in 1898. It was developed in two phases: numbers 20 to 44 West Walnut were built by 1890. The remainder of the street, Bancroft to Amory, was built in the rush of residential development between 1928 and 1930 by the developer Joseph Dupree, with Arthur Weinbaum and David Wexler as architects. Many had garages added at the same time.

Number 109 West Walnut is a twelve-family, brick-and-cast-stone apartment building completed on February 11, 1933, as the only apartment building on the street, and the last documented residential development in Egleston Square for thirty years. Hyman Schuman built it, and Weinbaum and Wexler were the architects. A corner store was added in 1937.

Atherton Street was also developed in two phases, the first half consisting of small, wood-frame houses with pitch or mansard roofs on small lots, largely built between 1875 and 1890. Skilled workers and foremen at the local factories and breweries might have owned these houses. The remainder of the street was built up from 1888 to 1897. Reflecting a higher-income, middle-class resident, these homes were bigger and built by skilled craftsmen architects in the popular colonial revival and Queen Anne styles. Seventeen homes were built about 1886-1888, after Atherton Street was extended to Amory Street. Building permits are scarce, but most homes were built between 1892-1893 and 1896-1900. Number 59, for which there is no information, is an early colonial revival house with double gambrel roof.

The earliest documented house was number 6 Atherton, built by the skilled architect-builder Peter Schneider, and completed on May 5, 1891. Schneider also designed and built the elegant stick-style house at 14 Egleston Street in 1897, today the finest house on that street.

48 Atherton Street, in May 2020

Number 48 Atherton Street was designed by Julius Schweinfurth (1858-1931), a significant Boston architect of private homes and schools (including the first major buildings at Wellesley College in 1904-1909). This house was permitted for Catherine Landers on November 1, 1892. A moonlighting job for Schweinfurth, who was employed as a draftsman for Peabody and Stearns at the time, it shows signs of the later use of the colonial revival and shingle styles of his domestic architecture. It is a large house with imposing, oversized, two-story bow fronts that support a wide gable resting on exposed rafters. The garage was added in 1905.

Number 42 Atherton is an exact replica built for Peter Busse, but there is no building permit. Number 44 – its building permit is lost too – is also very similar, except the two-story bay is polygonal in shape. Number 44 Atherton was owned by Rudolph Haffenreffer by 1919; he hired Jacob Liuppold to design a new piazza in August 1919. Both Landers and Busse had “auto houses" built at the back of their homes, indicating their wealth, since automobiles were expensive and uncommon in Boston neighborhoods at the turn of the 20th century. And most streets were still gravel. Busse had the first documented "auto house" in Egleston Square at the rear of his home. A wood-frame building built in 1902, it was replaced by a concrete garage with hip roof in 1909, built by the New England Cement Stone Company. Landers added her garage in July 1905.

X. THE SECOND APARTMENT HOUSES

The elevated rapid transit system transformed the residential landscape of Egleston Square like nothing else before, with apartment house living which gained increasing acceptance by the middle class after 1910. From 1910 until 1928, 38 multi-family buildings were built in the Square, bounded by Westminster, Walnut, and Columbus avenues and Bragdon Street.

On September 6, 1910, Simon Hurwitz bought a two-acre estate at the crest of Walnut Park, and built fourteen apartment houses on it between 1911 and 1912. The estate Hurwitz bought was that of Charles M. Clapp (1834-1897), who owned the Aetna Rubber Foundry on Brookside Avenue and Cornwall Street. In the rubber business all his professional life, Clapp had contracts with Goodyear Rubber for tires, and the Boston Fire Department in the manufacture and repair of water hoses. Clapp built his fine home facing Walnut Park about 1872. In 1925 the City of Boston built Cornwall playground on the factory site.

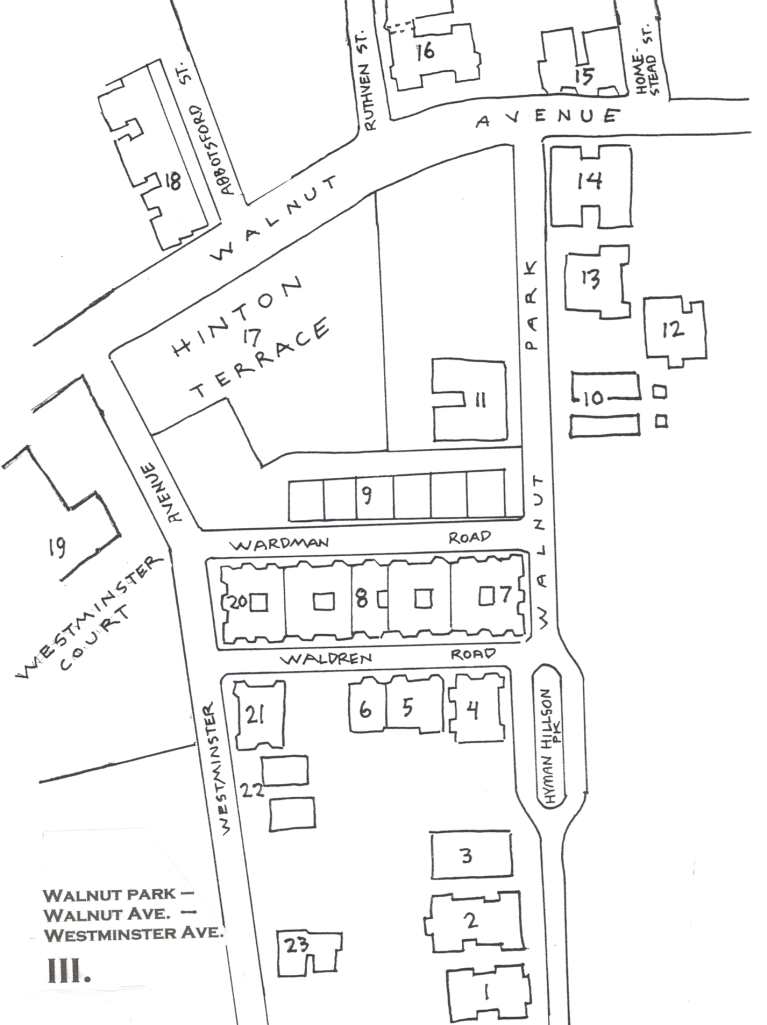

Hurwitz could justify the expense of what for that time was a very large and dense cluster of brick buildings because of greatly improved public transportation. The elevated trains that stopped at the new station down the hill could carry 500-800 passengers every eight-to-ten minutes into the downtown business district and connector subways. He built two new streets through the parcel named Waldren and Wardman roads; the City of Boston assumed ownership of them in 1927 and 1928.

Two architects were hired to design the large building blocks: Fred Norcross and Thomas M. James, who clearly worked as a team to create a harmonious group of buildings. James designed three detached apartment houses: numbers 50 Walnut Park, 65 Westminster Avenue and 15 Waldren Road. Norcross designed the entire row of five apartment buildings on Wardman Road between Walnut Park and Westminster Avenue, as well as 60 Walnut Park.

Fred Norcross (1871-1929) was arguably the most prolific and creative designer of apartment buildings in Boston. An informal list totals 110 Norcross-designed apartment houses between 1900 and 1929 in the North End, Beacon Hill, the Fenway, Back Bay, Roxbury and Brighton, mostly for Jewish developers. By far the most were in Roxbury. Norcross – a master in brick and limestone – was one of a select group of Boston architects who specialized in multi-family housing at the height of its popularity between 1910 through the 1920s: Saul Moffie, S. S. Eisenberg, S. N. Silverman, Samuel Levy, and Weinbaum and Wexler. These architects, almost all Jewish, were highly skilled in the arrangement of interior spaces. Norcross worked with Hurwitz, probably for the first time in 1906, to design a long, imposing, Romanesque apartment block at 367-395 Blue Hill Avenue.

Fifty Walnut Park, a six-family brick building with sandstone trim, was the first to be sold and leased out. It was permitted on November 23, 1910 and completed on December 11, 1911. Numbers 60 Walnut Park and 19 Wardman Road are two attached apartment houses completed on September 28, 1912. Number 60, and its twin at number 71 Westminster Avenue, originally had the distinctive high porch and cat's stone, twin knob posts.

Number 65 Westminster Avenue, designed by James, was a very high-end apartment building with six large apartments, two on each floor. In 1936 it was changed to fourteen apartments with two in the basement.

Wardman Road is five buildings of 27 apartments, also completed in September 1912. This block was built to resemble row houses as attached, three-family buildings with rhythmic window bays, individual classical-revival porches with round-arch doors below broken pediments, flanked by compound pilasters. On the opposite side of the street, Philip Glazer developed 8-20 Wardman Road in 1917, which consisted of six attached, three-family buildings designed by Samuel S. Levy. These were unusual because very little was built during World War I.

Six other apartment houses were built in the late 1920s on Walnut Park. Four were designed by Saul Moffie: numbers 24, 30, 38, and 72-76 Walnut Park, completed in 1926 and 1929. The most unusual of the Walnut Avenue apartment buildings by Moffie is number 72-76, built of yellow brick and set back from the lot line with high stoops. The two wide doors have elaborate casings of Art Deco decorations in cast stone.

On March 22, 1922 Henry Dinner bought the W. Dudley Cotton house, built in 1881, and on it built three apartment buildings designed by three different architects. The first completed was 361-383 Walnut Avenue in May 1923, designed by Arthur Rosenstein. Number 81 was designed by Samuel S. Levy and completed on May 23, 1925.

The yellow-brick building with the bold, red-tile cornice at 79 Walnut Park was completed in 1930. Designed by Silverman and Brown, it originally had a duplicate building at right angles to the street, but this was razed in the mid-1970s. That site today is occupied by a tidy community vegetable garden with a white picket fence.

Also in 1910 Norcross designed two wood-frame, three-family houses at numbers 71 and 73 Walnut Park for the owner and contractor Louis Greenblatt. They are the only documented wood-frame buildings by Norcross, who worked (almost) exclusively in brick, limestone and cast stone. Number 73 had curved wooden porches that were removed in the summer of 2011 by the contractor James Mahoney, who also smothered the wooden building in aluminum siding. Number 71 Walnut Park had a prefabricated, steel, portable garage built in the spring of 1918, set up by the Brooks Skinner Company of Quincy, a major manufacturer of prefab garages.

On August 10, 1910 Arthur Russell of the New England Cement Stone Company hired the architect Harold Eklund to design a block of four, three-family houses at 3-5 Westminster Terrace, a cul-de-sac carved out of the Elias Milliken estate. The Milliken family subdivided their lot into two equal, 12,000 square-foot lots, keeping their house on a smaller lot. Two buildings remain; the third at 7-9 Westminster Terrace has been taken down. The two remaining are rare, concrete-and-stucco buildings set at a right angle to Westminster Avenue. They have flamboyant Dutch gables facing the street and private way. The Milliken house, like many of the big mansions that dotted Westminster Avenue and Walnut Park, became a rooming house. It was damaged by a fire in 1991, and in 1997 acquired by Urban Edge, which restored the mansion and broke it up into five condominiums. Called The Residences at 19 Westminster, the restoration was done by the Narrow Gate Architects with Vertec Construction and completed in 2002.

Not all of the Clapp estate was built on: one 17,000 square-foot lot next to 65 Westminster remained vacant for ninety years. The west end wall of number 65 was built without windows in a cheaper grade of brick, suggesting Hurwitz may have planned a duplicate apartment house. In 2003 Urban Edge built two duplex houses of two units for first-time homebuyers, each on the lot. Designed by Stull & Lee, they were the first new homes in Egleston Square since Westminster Court was completed in 1967.

In 1900 Ellen Connel developed the first parcel on the newly-extended Bragdon Street, number 70-82, between Ernst and Miles streets. She hired George Edmund Parson to design seven attached, three-story apartment houses set back from the lot line with a fringe of green space. These were not completed until September 1906, suggesting Connel’s difficulty in getting the $100,000 construction financing.

Next to Hurwitz, the second major developer of apartment buildings in the square was Morris Weinstein. In July 1911, he hired S. N. Silverman Engineering to design a three-story, yellow-brick apartment building at the corner of Columbus Avenue and a new street named Dixwell, completed on January 12, 1912. (The present corner store may have been added later.) That same year, in December 1912, 12-20 Dixwell Street adjacent to the schoolyard was completed for Weinstein and designed by Norcross. Originally three, six-family brick buildings, a fourth, number 4-8 Dixwell, was razed in the late 1960s. A small, shady, sitting park occupies the site today.

On February 11, 1911 Weinstein bought two parcels totaling 35,000 square feet for $90,000 from the Roxbury Latin School. This land fronted Bragdon Street and two new streets, Bancroft and Ernst. In his second collaboration with Weinstein, David Silverman designed a complex set of seven buildings grouped around an interior court. Although designed at the same time, each has separate architectural features that give each some individuality. All were completed in December of 1912.

On July14, 1912 Max Wulf took out a $90,000 mortgage to build seven attached, three-story apartment houses along the block of 1841-1865 Columbus Avenue, from Bragdon to Dimock streets, designed by Fred Norcross. These are made up of rhythmic bays flanking round-arch doors with inset stairways and broad cornices. Like Silverman’s buildings, all are trimmed with light sandstone against walls of red brick. In September 1944 the New England Hospital for Women changed the occupancy to nurses' housing. After decades of neglect, the buildings at 1841-1865 Columbus Avenue were half-empty shells with many windows gone. Urban Edge bought the buildings and spent $1.5 million for a total rehabilitation of every apartment in all the buildings, with Stull & Lee as the architects. This project was completed in 1983.

XI. THE AUTOMOBILE GARAGE

The increased popularity of the automobile in the first decade of the 20th century brought with it a new type of architecture: the automobile garage, repair shops and filling stations. The earliest documented public garage was built soon after the Wardman-Westminster apartments. On August 7, 1912 the Egleston Square Garage Company obtained a building permit for a garage and filling station at 3033 Washington Street and Columbus Avenue. Designed by Harrison Atwood, it included a triangular lot fronting Columbus Avenue for a gasoline station (more than likely for Standard Oil). The first gas station in Egleston Square, and one of the first in Jamaica Plain, it is a Mobile station today (2017).

After World War I, four more garages were built. The Walnut Avenue garage was built in 1919 by George Kimball at 3050-3058 Washington Street, opposite the Egleston Square Garage. This was designed by A. J. Carpenter (the architect of the commercial block of 3096-3104 Washington Street) in 1908. He used the grade change of Walnut Avenue to place garage doors on Walnut Park, and storefronts with big show windows on Washington Street, for automobile showrooms like Kulvin Auto Sales, who specialized in Packards, Hudsons, Essexes and Studebakers.

Westminster Motors at 3012 Washington Street, at the corner of Westminster Avenue, opened in 1927. Designed by Saul Moffie for the Exchange Realty Trust, it began as public parking, service and auto sales. Over time it was a Moxie Company distribution center, a shipping warehouse for hosiery, and lastly the Signs By Design sign shop.

A purpose-built garage was erected in 1924 by the Reardon Building Trust at 1890 Columbus Avenue at Bragdon Street, a very large lot on which James McNaughton designed a building, first for a truck rental-and-storage company, and later a parking-and-service station for several cab companies, notably Yellow Cab and Columbus Cab. The cab dispatch office and waiting room was located at 1967 Columbus Avenue, directly opposite the bus station. In 1977, Walgreen's department store was built on the site, designed by Asfour Associates for the Mark Investment Company. It opened at Christmas 1997.

The only garage still in use today was built in 1919-1920 for Morris Waldman of Chelsea, at 3162 Washington Street, at the corner of Chilcott Place. Designed by Nathan Douglas, its entrance was on Chilcott Place, with stepped-up front and gable roof. Likely built for the apartments and houses on Chilcott Place, it was enlarged to Iffley Road in the mid-1930s, with a brick addition and open-air car lot for Sidney Freedman's repair garage and used car showroom. Today it is a used-car lot and the auto mall JP Auto Plaza.

The large open lots on Columbus Avenue were ideal for automobile-related businesses, which required space for repair garages, storage tanks, pump islands, parking, and sufficient room for oil and gasoline tank trucks to make deliveries. Unknown a decade earlier, the architecture for the automobile age was a part of the urban landscape by 1920.

A two-bay automobile repair garage and filling station was built in 1927-1928 by J. F. Delancey at 1891 Columbus Avenue at Bancroft Street. This was expanded in 1929 for the Roxbury Gas Tap Company for storage and sale of range oil for home heating. The garage and gas station building was replaced with a new building on November 9, 1940 for the Miller Oil Company, designed by Weinbaum & Wexler. It has been an auto repair shop since 1997.

XII.

By about 1905 most of the streetcars had been relocated to the corner lot at Columbus and Washington streets, from which cars arrived and departed. After 1909 they removed to the Bartlett Street Yard outside Dudley Square. In 1921, John Donnelly & Sons Outdoor Advertising acquired the old horsecar and streetcar barns at School and Washington streets. In 1922 it added a brick addition to replace the wooden car sheds.

Also in 1922 the City of Boston, facing the increased school population, added a big new building to the Putnam School at 61 School Street, designed by Joseph A. Driscoll. It was named after former president Theodore Roosevelt who had died in 1919. The school opened for classes in 1923. The Hernandez School removed to the building in 1987 from its original location at 370 Columbia Road. (The old Putnam School had been taken down after World War II for a school playground.) The school was renamed after the Puerto Rican poet Rafael Hernandez, which just as Beethoven Street did a century earlier, reflected the demographic changes of Egleston Square.

Radio and Television appliance stores opened up in the square during and after World War II. One of the first was at 1985 Columbus Avenue in a store John Beden built into number two Weld Avenue about 1913, one of the Cox-built homes. A duplex, Beden lived in, or rented out the other half. By 1945 the Electric Sound and Radio Company, which specialized in Philco radios, leased the store. Both the house and store were taken down in the early 1970s, a victim of fire. Robert Lawson started an open-air fruit-and-vegetable market on the lot, managed by Pablo Garcia, which operated for about thirty years. In 2008 he built a double storefront on the corner. Lawson opened a barbershop at 1979 Columbus Avenue in 1967, and was burned out in the same fire. He rebuilt and bought the entire block of 1971-1979 Columbus Avenue that his daughters own today (2017).

In 1948 Saul Moffie designed a building for Sarah Gerber at 1900 Columbus Avenue called Gerber Radio Supply, opposite the gas station. A second story was added in 1952. On June 10, 1968 Grace & Hope Mission completed the conversion of the corner building with a ground-floor church with back-room offices and an upstairs living quarters. Grace & Hope Mission was founded at Baltimore in 1914.

Two events changed Egleston Square in the 1950s. The bus – an abbreviation of omnibus – replaced the streetcar in 1955. The tracks were torn up, the electric poles taken down, and Columbus Avenue and Seaver Street were reconstructed as divided, four-lane roads. Instead of clanging streetcars, long orange buses chugged out of the station on the same routes to Mattapan, Copley Square, Dudley Square and Forest Hills. Egleston Square remained a transit hub.

On July 16, 1953 Mayor John B. Hynes opened the Egleston branch library. In 1951 the City acquired the half-acre Katharine Dahl estate, built about 1867: a three-story house with carriage house, greenhouse and gardens, a reminder of the first Egleston Square. Architect Isidor Richmond of Richmond & Carney Goldberg designed a sleek, modern, International-style library with wide glass windows, still the most modern building on Columbus Avenue. Olmsted Associates, the successor firm of F. L. Olmsted, landscaped the grounds.

Born in Chelsea in 1893, Richmond graduated in MIT's class of 1916, and served in World War I. After the war, he apprenticed with Ralph Adams Cram. In 1923-1925 he traveled Europe on a Rotch traveling scholarship, drawing old synagogues, and returned to open his own practice in 1925. After service in World War II he formed a partnership with another Chelsea-born architect, Carney Goldberg, in 1946. Richmond died at age 94 in 1988.

XIII. URBAN RENEWAL

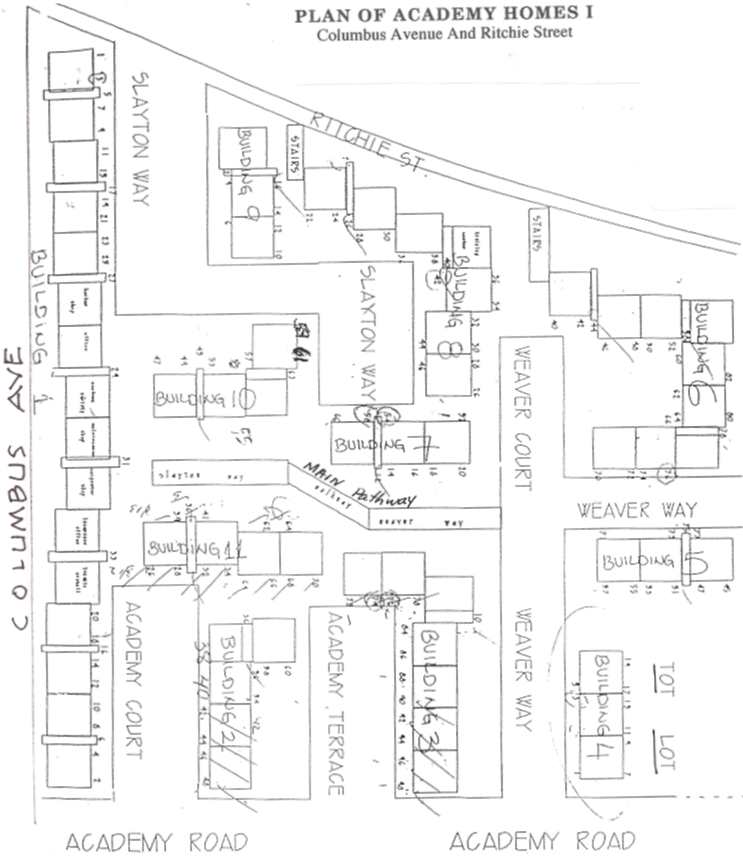

The second half of the 20th century at Egleston Square was one of tearing down and building up with new architectural forms. On May 16, 1963, the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA, today the Boston Planning & Development Agency) bought the fourteen-acre Notre Dame Academy as a site for Washington Park Urban Renewal replacement housing. On June 24, 1963 the BRA agreed to complete site preparation, including razing the Academy buildings and rough grading the interior roads. On 7.4 acres eleven, three-story buildings of cluster housing were built with 202 apartments designed by Carl Koch (1912-1998). The project was planned for those displaced from site clearance of the side streets near Dudley Station to build Warren Gardens homes and the Civic Center (library, courthouse, police station, and Boys & Girls Club).

This area was the poorest part of the 502-acre urban renewal district, and BRA director Edward Logue handpicked Koch, who had devised a low-cost construction method that would keep building costs and hence rents down. Koch had invented a system of prefabricated, interchangeable parts that fit together for a variety of sizes, called Spancrete. But contractors had limited experience with putting the notched pieces together for load-bearing walls and floors; non-load-bearing walls were made of factory-built, prefabricated stressed plywood. This inexperience caused structural damage that plagued the development for decades. Nevertheless, Academy Homes I was so important that Housing and Home Finance director Robert C. Weaver participated in the groundbreaking ceremony on May 10, 1963 at Columbus Avenue and Richie Street. (HHF was the predecessor to HUD. Weaver [1907-1997] was its first director. One of the interior roads of the development was named Weaver Way in his honor.)

The Development Corporation of America built out the site over the next four years. It was completed at the end of 1966 for a total cost of $3 million. Academy Homes was a self-contained little village, like all the WPUR housing, of identical boxes made of interchangeable parts facing private ways; the other private way was named for urban renewal program director William Slayton (1918-1989). Progressive Architecture gave Academy Homes I a citation for advanced residential design in its January 1965 issue.

Egleston Square was at the very tip of the Washington Park urban renewal boundary and so spared most of the wholesale clearance and resident relocation that affected large tracts of Roxbury. One tract was affected: a companion development to Academy Homes built between Townsend and Cobden streets, a 315-unit cluster development called Academy Homes II, designed by Carl Koch using the same prefabricated factory-built walls, panels, floor units and girder panels. The Land Disposition Agreement was signed on June 30, 1966 between the BRA and the developer Academy Cooperative Homes Inc. for $4.1 million. A very steep site of about five acres with 81 two- and three-family, largely wood-frame homes on two streets, Cobden Park was at the crest of the ridge and Codman Hill that came off Washington Street.

After site clearance, five huge, pre-cast monoliths of three-to-nine stories rose above, and sat far back from Washington Street. All entrances to the apartments came off Codman Park. One low-rise cluster faced Cobden Street with doorways on that street. The largest building was a nine-story, zig-zag monolith supported on wide, pre-cast concrete plinths, set deep into living rock. These plinths supported the prefabricated housing boxes and overhanging bays. One retail store was built into the ground floor of one the nine-story buildings facing Washington Street and the parking lot. Building permits were issued on June 29, 1966 and renters began moving in at the end of 1967, with the development completed in July 1968. The rushed construction cycle would have disastrous results for this development.

At Cobden and Washington streets, a 14,000 square-foot lot was cleared in 1965 as part of WPUR, when six wood-frame, three-family homes were razed. The BRA planned that corner for commercial use. A young husband-and-wife team of architects, Marvin Goody and Joan Clancy, designed a two-story masonry building in 1969 for La Parisiene Beauty Salon, which opened on March 21, 1971.

At the crest of Westminster Avenue (number 301), the Development Corporation of America, in a private partnership with Carl Koch, bought the three-acre Howard-Hersey estate on October 1, 1965. Called Westminster Court, Koch designed two buildings using the same prefabricated building technique he used at the Academy developments, but with much higher quality and carefully-supervised construction. Showing what can be done with competent contractors, the result was a handsome cluster of low-rise, attached homes arranged around a massive outcrop of Roxbury conglomerate. Two C-shaped buildings faced each other around the outcrop, creating a courtyard. Entrances were both from Walnut Avenue and Westminster Avenue, as well as the Cobden Street parking lot. This was not an isolated village like the Academy I. It was completed and fully occupied by March 14, 1967.

The land adjacent to the MBTA bus station had long been subdivided into house lots, with one or two houses. Using urban renewal financing, the BRA took those lots at Columbus Avenue and four others and joined with the Boston Housing Authority to construct an elderly housing development. Architects Isidor Richmond and Arnold Jacobson were hired in 1968, and they submitted plans in April 1968 for a twenty-story tower of 168 apartments. Richmond had experience with public housing authorities: in 1936 he was an associate architect in the design of Newtowne Court, the first public housing development in Cambridge. The only circular tower in Boston, the elderly housing tower can be seen as far away as the Arnold Arboretum. It opened and was fully occupied on June 23, 1970. Surrounded by a shady sitting park, the Roundhouse, as it is colloquially called, is a textbook example of the tower-in-the-park idea so beloved of Le Corbusier and other International Style architects as early as the 1920s.

The architects Stull & Lee used the same concept in their design of Council Towers at 2863 Washington Street for the Council of Elders. It was completed on January 14, 1986 and is surrounded by shady paths and sitting areas. Set on a five-acre site, the 180-foot tower is on the location of the Academy of Notre Dame building razed by the BRA over twenty years previously. The sixteen-story high-rise building is almost on the site of the P. C. Keely building. Council Towers is set far back from the street with a circular drive on immaculate grounds. The original stone wall of the Academy frames the front of the drive. It has 145 apartments for low- and moderate-income seniors. It cost $6 million to build.

The BRA took four more house lots on Columbus Avenue, including the old F. W. Kittredge house, built about 1870, opposite the Hernandez School playground, to build what BRA director Hale Champion – who succeeded Edward Logue in 1968 – called “instant housing.”

Building housing that was affordable for low- and moderate-income families was the goal of WPUR, and using prefabricated construction systems (as at Academy Homes) was the favored method, since 75% of land disposition was funded by the Federal Housing Administration. Construction financing came from more traditional bank sources.

Sepp Firinkas was the structural engineer with Koch on Academy I & II, and in 1968 became involved in a third housing venture. In 1968 Champion announced his plan to build on 300 scattered, city-owned sites, using a construction style devised by Firinkas and architect Don Stull, using prefabricated concrete, brick and wood slabs notched together to form housing boxes. They planned four, three-story block buildings on a 58,000 square-foot parcel surrounded by gardens and parking spaces. The plans were submitted on March 6, 1971 for 46 units. The project was abandoned by the end of 1972, when investors went bankrupt in the wake of the Nixon administration's decision to stop funding urban renewal projects. This “instant housing” was left as abandoned, empty shells all over the city for over a decade.

On July12, 1984, BRA director Robert Ryan designated Urban Edge to own and rehabilitate the four buildings at numbers 2000-2030 Columbus Avenue, using one of the first Mass Housing Partnership grants through the Mass Housing Finance Agency (today MassHousing). Tennant Gadd Architects partially rebuilt and completely renovated all 34 apartments, and added office space in one building for Urban Edge at 2010 Columbus Avenue. The buildings were completed and occupied in June 1987.

XIV. THE END OF THE ELEVATED

On May 2, 1987 the elevated trains ceased operation after 78 years, when the new Orange Line opened on the old railroad right-of-way that paralleled Amory Street. On that day too, Egleston Square ceased to be a transit hub. In three years the elevated station, platforms and train beds suspended on iron legs would be gone. The new Jackson Square station and its busway replaced Egleston Square as the terminus for the Ashmont and Mattapan surface transit routes, although still stopping at Egleston.

After 1990 a new Egleston Square would emerge around the crossroads of Columbus Avenue and Washington Street, which would replace the transit terminals which had defined it for a century. What began first was preservation of the original housing stock. In 1984 Urban Edge participated in the largest HUD program of foreclosed multi-family properties in the nation: the 1171 units owned by Gem Realty called Granite Properties. Facing criticism from Senator Edward Brooke that Urban Renewal was creating too much land clearance and displacement, Robert Weaver, who became the first secretary of the renamed and reorganized Housing and Urban Development (HUD) agency, revised redevelopment from renewal to rehabilitation with private-sector participation.

In December 1967 Weaver came to Freedom House to announce the allocation of $24.5 million for the rehabilitation of 2,074 units in Roxbury called Boston Reinvestment Program (“BURP”). This was Urban Renewal part II. Administered directly out of the Federal Housing Administration in Washington, not the BRA, teams of real-estate developers were hand-picked to participate. Maurice Simon and his partner Sidney Insoft, with offices in Brookline, took the largest number, 1030 run-down units, scattered from Grove Hall to Egleston Square. They agreed with the requirement that each apartment would be rehabilitated for $12,000.

Working out of his law office, Simon was inexperienced in large-scale housing rehabilitation and property management, but more tragically, in the relocation of families (during WPUR the BRA had professional relocation specialists in a separate office in Roxbury). During what was often the gut rehab of units, BURP was not successful.

In 1974 HUD expanded on the program with Section 8 of the Housing Act of 1937, which provided rental subsidies of 70% for each renter, based on income. The private market got mortgage insurance and a dedicated rental stream, and the government got out of the housing-ownership business, for a time. All this came crashing down on Egleston Square in 1981-1983, as hundreds of privately-owned units were left mismanaged, and Gem defaulted on its mortgages; by that time Simon had died.

In 1985 Urban Edge, under then acting-director Mossik Hacobian, was designated owner of seven properties: three on Walnut Avenue, one on Walnut Park, two on Waldren, and 3224-3234 Washington Street at Forest Hills Street; a total of 170 apartments, all with renewed, project-based Section 8 vouchers. Most of the renovation of the Granite Properties was completed in 1989. This ushered in the age of non-profit, community-based social housing agencies, owning and managing multi-family housing.

Urban Edge was founded by Ron Hafer as an outgrowth of the home ownership program of the Ecumenical Social Action Project in 1974. It feared that the Jamaica Plain-Roxbury edge along Columbus Avenue would gentrify after the removal of the elevated rail, attracting a more affluent professional to live in close proximity to the downtown. In response to this, Urban Edge shifted to housing preservation, beginning in 1981 at Dimock-Bragdon apartments on Columbus Avenue.

Number 361-383 Walnut Avenue, at the corner of Walnut Park, is a twelve-unit apartment building designed by Arthur Rosenstein and completed in1923. This was one of the properties Urban Edge acquired from Gem Realty through the Boston Housing partnership/HUD disposition of 1984. Thirty-eight Walnut Avenue was acquired by Urban Edge in November 1987, and it completely renovated the twelve-family apartment building with Tennant Gadd Associates architects, originally built in 1926 and designed by Saul Moffie. The Walnut Avenue and Walnut Park buildings each cost $500,000 to renovate.

The two Waldren Road apartment houses were part of the Hurwitz development completed in 1912. Many apartments owned by the Wardman Trust were also in trouble; these included the Wardman Road block, 71 & 65 Westminster Avenue, and 81 Walnut Park. A total of 100 apartments, these were under HUD receivership by 1975.

On September 28, 1979 HUD sold the portfolio with project-based subsidies to Lorenzo Pitts for $485,000. In 1999 Pitts declined to renew the subsidies, and Urban Edge – already invested in adjacent Walnut Park and Waldren Road housing – stepped in and bought all the buildings on September 7, 2000 for $1.95 million, and extended the project-based subsidies, thus insuring every resident who qualified could remain. Urban Edge hired Icon Architects and Macomber Construction to design and build out a major restoration of each building, with renovation of every apartment from kitchen cabinets, heating systems, roof and masonry repairs to all brick walls. The $10.7 million project was completed in December 2001.

On October 17, 2011, 71 Westminster Avenue, and the attached three-family buildings at 3-5-7 Wardman Road, were totally destroyed by a huge fire caused by an intentionally set gas explosion, displacing 24 families – one of the worst disasters in the history of Egleston Square. The buildings were razed in March 2012 by Urban Edge. It hired Icon Architects to design new buildings in architectural sympathy with the original apartment houses. A ribbon-cutting took place for the new buildings on November 16, 2013. Load-bearing brick walls of 1912 were now too costly, and were replaced by a wood-frame structure with brick veneer. The cast-stone porch was also not feasible to reproduce. The cost of the new buildings was $4 million.

In 1995 all 202 renters at Academy Homes I were confronted with a 14% rent increase by the Development Corporation of America, that developed it through the Washington Park Urban Renewal program. The thirty-year rental subsidies would not be renewed; DCA wanted to go market rate. In April 1998 Urban Edge and the Academy Homes Tenant Council bought all eleven buildings for $6.8 million. Beginning in April 1999, Mostue Associates architects did a complete renovation of the buildings and all apartments; the grounds were also re-landscaped. The total cost was over $12 million, financed through a myriad of city, state and tax credit sources. It was completed on May 8, 2000.

In the twenty years between 1981 and 2001 Urban Edge had spent nearly $50 million in housing preservation of Egleston Square. Academy Homes II was beyond saving. It had been so poorly and hastily built that within six months of completion a section of roof blew off in February 1968. For the next thirty years the residents were subjected to owners going in and out of foreclosure and a series of new out-of-town owners. In 1992 HUD sued the Pennsylvania-based owner David Altman for mismanaging rental subsidies. With the help of then-congressman Joseph Kennedy, HUD finally foreclosed and was forced to buy it back on June 28, 1995 for $4 million.

A study concluded in 1996 declared the development unfeasible to renovate – some engineers feared the buildings would collapse within five years. The entire hillside development was razed between February 2001 and January 2002. The plan was total redesign and rebuilding of the entire development. Chia Ming Sze and Elton Associates were selected as architects; Paula Collins of the Chia Ming Sze firm was the principle architect.

Recognizing a crisis, HUD hastened to add Academy Homes II to its Demonstration Disposition Program in 1996, and allocated funding the next year. It designated MassHousing to rebuild and manage the new Academy Homes II. (HUD still owned the property as opposed to Academy I, which after considerable negotiation was transferred to Urban Edge and the AHTC.) Groundbreaking for the $46 million rebuilding of Academy Homes II took place on September 28, 2001, with Mayor Thomas Menino, Congressman Michael Capuano (who succeeded Kennedy in 1998) the United Residents in Academy Homes (URIAH) president Gloria Bowers, and the architect Nick Elton.

Collins designed a series of twelve, six-and-ten-unit, wood-frame clusters of three-story attached houses on Codman Park and Washington Street. In part because of the difficult steep slope prone to erosion, and in part because URIAH loathed the monolithic blocks (they wanted to live in homes), the number of units was reduced from the original 315 to 216. The plan also included a wide, spacious community center in the valley of the hillside facing Washington Street, with a drive to the Washington Street homes parking lot.