A History of St. Thomas Aquinas Church

St. Thomas Aquinas – the Mother Church of Jamaica Plain and West Roxbury – turns 150 years old in 2019. The seat of the Catholic faith in Jamaica Plain; out of it grew the churches of Our Lady of Lourdes and St. Andrew the Apostle.[i] St. Thomas was established in 1869 and the church dedicated on August 17, 1873, the year before Jamaica Plain (as part of the Town of West Roxbury) was annexed to Boston.

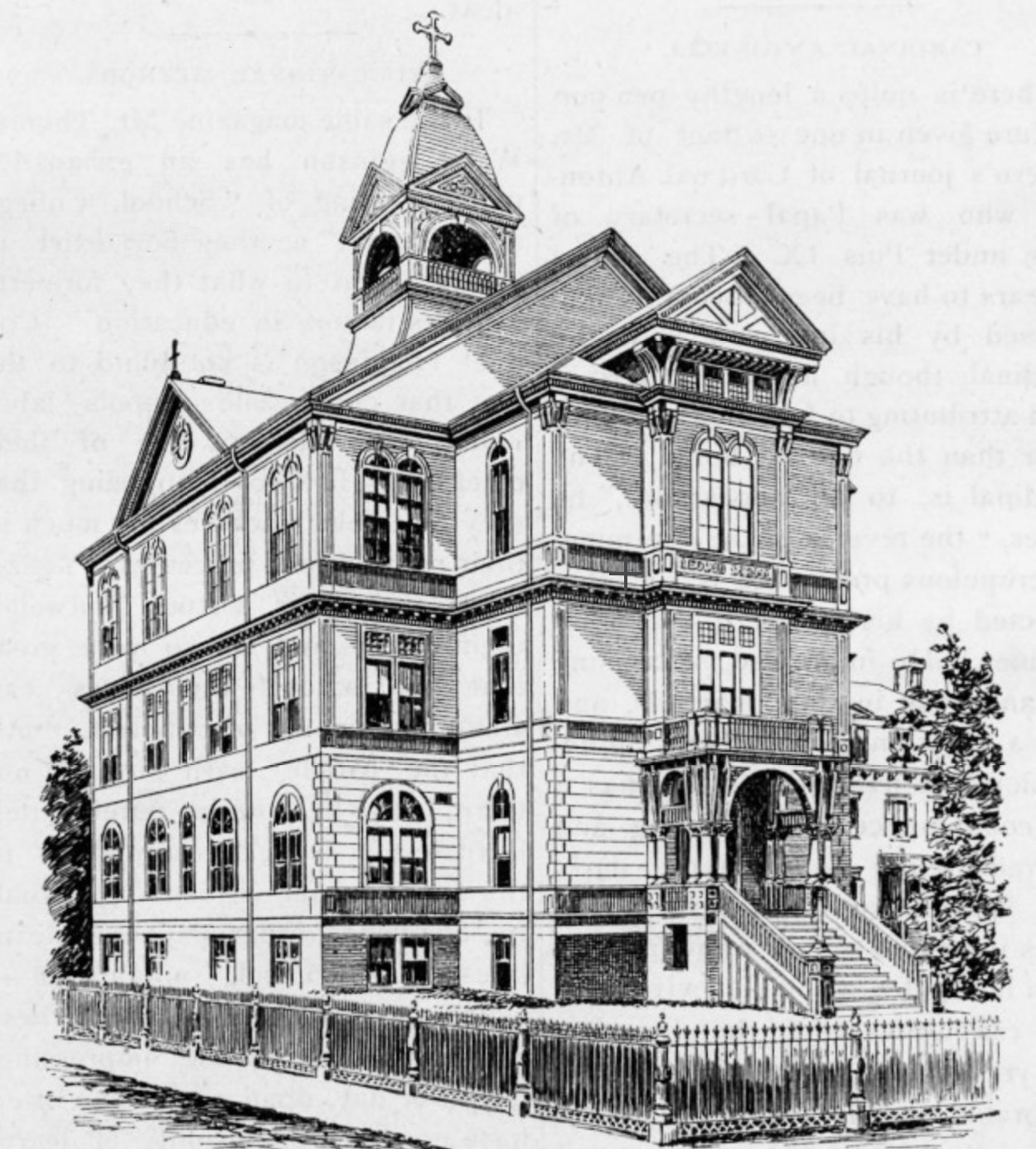

The original St. Thomas Aquinas Church designed by P.C. Keely. From a postcard, about 1915. Courtesy of the Archives of the Archdiocese of Boston.

The first Catholic Church in Roxbury (of which Jamaica Plain was a part until 1851) was St. Joseph’s Church. It was built in 1846 and was located just outside Dudley Square; tucked off of the Norfolk and Bristol Turnpike (Washington Street). St. Joseph was established by Father Patrick O'Bierne, and its parish included all of Roxbury, Dorchester, Brookline, Hyde Park, Dedham and Norwood. [ii]

After the Civil War, Irish Catholics found employment in Jamaica Plain as domestic servants, gardeners, horse trainers, coachmen, laborers, and mechanics at the factories along the railroad. They were numerous enough for Archbishop John J. Williams to consider establishing a church in Jamaica Plain. Thus, in 1867, he asked Father O'Bierne to select a site and start a church.[iii] It was not uncommon in Boston for Protestant property owners to discourage Catholics from buying property. But Father O'Bierne found a goodly man in Abner Child of Jamaica Plain. Child agreed to sell – likely at a discount – 1.5 acres of his estate on South Street, adjacent to his own house at 65 South Street. O'Bierne bought the parcel on June 18, 1867. The site was ideal: 200 feet long on a main street, not far from the Town Hall, and not in an obscure corner like the location of St. Joseph Church. Here O'Bierne could build right in the town.

Father O'Bierne selected his assistant priest from St. Joseph, Father Thomas Magennis, to oversee the new church. Fr. Magennis was 26 years old and was ordained only two years earlier on December 28, 1866. Fr, Magennis was an energetic young man and he quickly set to work not only raising funds for the new church but making friends for his new parish. He arrived on January 4, 1869 and moved into 793 Centre Street next door to the First Congregational Church (First Church in Jamaica Plain, Unitarian Universalist). He rented the house from Dr. Francis Minot Weld.

Magennis was born in Lowell on March 7, 1843 on the Feast of St Thomas his patron saint. He was raised in Worcester and graduated from Holy Cross College. Archbishop Williams gave permission to name the new church on South Street after Father Magennis's patron saint. It is the only Catholic church in Boston named after the founding priest. Magennis celebrated his first mass at his new home in January 1869. But the spirit of ecumenism and good will prevailed and and the Reverend C. H. Doyle of the First Congregational Church offered his building for saying mass.[iv] The Board of Selectmen of the Town then voted to allow services to be said at the Town Hall, and Father Magennis celebrated mass there for the next eighteen months.[v]

Father O'Bierne began planning the new church and probably had retained the architect before Magennis arrived. The town was generous to the building fund; many of the best names of the town, familiar even today, gave money:

Nelson Curtis

Andrew J. Peters

Dr. George Faulkner

Robert Keddie

George Bowditch

Moses Williams

Robert Seaver (the grocer)

George Harris

Charles Rogers

Thomas Evans

Abner Child also gave a large sum to support the poor families of the parish.[vi]

The redesign of the facade of St. Thomas Aquinas Church (view from Child Street), about 1940. Courtesy of Richard Heath (personal collection)

As will be seen, education became a central feature of St. Thomas Aquinas. Appropriately the site was opposite the Child Street Primary School, a school built in 1856 and renamed the Bowditch School in 1862.[vii] The site was also next door to the Metropolitan Horse Railroad waiting room, barn and stable built in 1858 on Jamaica Street.[viii] The land was owned by Stephen Minot Weld, who also owned land around what is now "the Monument" at Centre and South streets. Weld was a major stockholder in the horse railroad. He petitioned the selectmen to lay tracks down Centre and South streets. His widow Elizabeth sold off another parcel to the horse railroad. By 1879 the horse railroad owned 1.5 acres with a four-track car barn, a machine shop, and large brick stable facing Jamaica Street. There was a changeover to electric streetcars in 1891-1892. The South Street and Centre Street tracks were rebuilt to take heavier cars and a new eight-track barn was built.

For the design of the new church, O'Bierne turned to Patrick Charles Keely of Brooklyn. Keely had designed four Boston Catholic churches, and, at the time, was supervising the construction of his magnum opus, the Cathedral of the Holy Cross on Washington Street in the South End. Keely designed the Cathedral for Archbishop Williams (who is buried behind the altar screen), so there was no question that Keely would design a modest suburban church for Jamaica Plain, which was also the flagship church for the growth of the Catholic faith west of Roxbury. At the time, Keely was the greatest architect of Catholic churches in the United States, and in 1870, was at the height of his career. Very little remains today of Keely's building for St. Thomas Aquinas, and there is scant documentation about its design and subsequent alteration. But what he did design was truly unique, not only in his own career but in contemporary Catholic Church architecture in Boston.

Patrick C. Keely was born in Kilkenny, Ireland on August 9, 1816. He was apprenticed to his father, an experienced and respected architect and builder. Keely emigrated to the United States in 1842 and settled in the Fort Greene neighborhood of Brooklyn.[ix] He began his career as an artisan carving altars. In the 1840s in the United States, the profession of architect was barely known; that of an Irish architect was unknown. Nevertheless, Keely was given the opportunity to design Sts. Peter and Paul Church in Williamsburg (New York), built in 1847-1848.[x] With this project, "Keely became successful overnight, for the Irish priests did not forget their fellow countryman who was generally the only celebrated Irish architect within their knowledge" (Purcell, Records of the American Catholic Society).

Most Holy Redeemer Church in East Boston (built 1857). The campanile on the right side is similar to the design Keely did for St. Thomas Aquinas. Photograph by Richard Heath, 2019

Keely's first church in New England was St. Mary's Church in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1848.[xi] His first church in Boston was St James Church on Albany Street in 1855; it was later replaced by a newer church on Harrison Avenue in 1875. His second church in Boston was Most Holy Redeemer in East Boston, built of Rockport granite in 1857. Keely designed churches from Detroit to Burlington, Vermont, Cleveland to New Jersey and New York City to Boston, where he did most of his work. The number of his projects is uncertain, but the best estimate is 150 buildings. This does not include remodeling of existing churches or the design of Catholic institutional buildings such as Notre Dame Academy or the House of the Angel Guardian in Roxbury (both since demolished). Keely designed twelve churches in Boston, including two in Charlestown, two in East Boston, three in the South End, and one downtown church, St. James the Great, on Harrison Avenue. He also remodeled two older churches in South Boston.

Keely suffered a stroke in 1890 and shortly after formed a partnership with his son-in-law and chief draftsman, Thomas Houghton (1843-1913), to form the firm Keely and Houghton.[xii] Keely died of heatstroke at the age of 80 on August 11, 1896.[xiii]

Keely submitted his plans for the church structure to Father O'Bierne, and likely also to Father Magennis, sometime in 1869. Work began quickly afterwards. Local legend has it that loyal parishioners (and no doubt all the local kids) came out to help Father Magennis dig the first shovels of dirt for the foundation.[xiv] Foundation stones of Roxbury Conglomerate were donated by a local quarryman named Scott. The stones were likely obtained from the vast Parker Hill quarries. These hand-cut blocks were carried along South Street by teams and set in place. The cornerstone was laid on August 15, 1869, "with all the solemnity of the Roman ritual by his Grace Archbishop Williams… . A vast gathering of people witnessed the rites."[xv]

Keely designed a long, narrow brick nave church with flanking aisles, 165 feet long and 68 feet wide. It had a steep Gothic roof all covered in slate. Brick buttresses supported the roof, and between each were set tall narrow stained-glass windows along the inside aisles. The most remarkable feature was the 194-foot tall narrow brick campanile on the east corner. Twice as tall as the church, the tower was crowned with a conical roof supported by four Gothic posts which held up the church bell. On the tall, conical, copper cap was set a simple cross. No doubt, this was never built due to the economic depression of 1873, one of the worst of the 19th century. Instead, the bell was first set in a Gothic style bellcote, which was about as tall as the arched doorway.

Plan of St. Thomas Aquinas Church, rectory and convent, 1874. From George W. Bromley, Atlas of the City of Boston: West Roxbury

The lower church was complete enough by the end of 1870, or early in 1871, to allow for masses and prayer services. This area is the Father Thomas Hall we know today.[xvi] St. Thomas Aquinas Church was dedicated by Archbishop Williams on August 17, 1873. According to the Globe, "The dedication attracted thousands, many of whom were Protestants, and all of whom contributed generously to the work." [xvii] The newspaper piece went on to describe the structure:

The tower and spire of the church have not yet been built. The place destined for them is at the north corner of the church and when completed, will be in height 194 feet. On the south corner is a neat little bellcote, which relieves the facade of the building. On entering the church the visitor is agreeably surprised by the beauty of the fresco paintings… . The high altar is built of French Caen stone, is massive but relieved by beautiful carvings… [including one of] St. Thomas… The reredos is of very ecclesiastical design, towering, by three carved pinnacles, towards the roof and set off in the background by a realistic painting of the ascension of Our Lord.[xviii]

Two statues, one of St. Thomas and the other of St. Patrick, were on the right and left of the sanctuary, both donated by a member of the congregation. The statues were set off by a bright background. Finally, there was a forest of thick, wooden cross-beams supporting the steep, arched roof.

The edition of The Pilot for August 23, 1873, described the interior in detail:

The church is built of face brick with brown stone trimmings. The most attractive feature is the frescoing by which the interior is beautifully set off, unsurpassed by any work by W. S. Brazer, the well-known frescoer of Boston. The general design is a most ornate and lavish one…pleasing and brilliant colors characterized by a florid style reflecting the highest credit of the artist. The mason work was furnished by Mr. McGilcuddy and the carpentry by Mr. Wigglesworth.[xix]

Fr. Thomas Magennis, Centennial of St. Thomas Aquinas Church, 1969. Courtesy of the Archives of the Archdiocese of Boston

Brazer also painted a mural for Our Lady of the Assumption Church in East Boston. That is another building designed by Partick Keely and it was dedicated just three months after St Thomas Aquinas (in November 1873). The mural that Brazer created there is of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary and is in the huge circular arch behind the altar. It remains in place (as of 2020).

The entire cost of construction was $80,090; about $1.7 million in 2019 dollars. Soon after the church was completed, an additional parcel of land was purchased extending the church property to Woodman Street.

The church building could seat 1200. A "very sweet-toned organ accompanied the solemnities of the church."[xx] A Globe article explained that in 1888, "now four masses are celebrated. A well-trained choir furnishes the music at high mass each Sunday, while the little children sing at each of the earlier masses."[xxi] The organ was replaced about 1895 with an E. and G.G. Hook organ that came from St. Paul's Church (now Cathedral) on Tremont Street. It was built by the famous organ makers at their Tremont Street (Roxbury) shop in 1854, and is one of the oldest pre-Civil War Hook organs in the United States.[xxii]

In the foyer of the church was set a plaque honoring Abner Child for his generosity to St. Thomas Aquinas church: "In memory of Abner Child. An honest, faithful and useful man."[xxiii]

There were sixteen elegant stained-glass windows set between each buttress. These were probably designed and manufactured by Franz Mayer Company of Munich, Germany. The company designed the magnificent stained-glass windows for Holy Cross Cathedral, which, by 1873, was well underway. Founded in 1847 as a manufacturer of decorative arts, in 1860 the Franz Mayer Company began to design stained-glass windows popular in Europe and the United States. It had an exclusive contract with the Vatican. The statues for the Stations of the Cross were cast in high relief, carefully painted plaster, set in Gothic frames with floral borders, also likely designed by Franz Mayer.

Rectory and Church about 1910 with Pope Leo XIII School in the background. Postcard from the Archives of the Archdiocese of Boston.

In 1869, Father Magennis was elected to the West Roxbury School Board, but he shared the view of Archbishop Williams that Catholic children deserved an education steeped in Catholic traditions. There was also the sense that Irish children, especially girls, were marginalized in the public schools.

On October 2, 1873, Father Magennis invited the teaching order of the Sisters of St. Joseph from Brooklyn to form a school at St. Thomas Aquinas. He had visited the Sisters in Brooklyn and had been impressed. Sisters Regis Casserly, Claire Corcoran, Mary Delores Brown, and Mary Felix Cannon arrived at the parish on October 6. They set up a school in rooms partitioned off from the basement of the church, and developed a curriculum and schedule for 200 girls. Boys were admitted in 1877. Father Magennis believed in co-education and there were no separate classrooms for boys and girls.[xxiv]

A five-room house on Harris Avenue owned by Dr. Joseph Winkler was bought and moved to the church grounds as a convent for the Sisters. The 1865 map for West Roxbury shows a large house on the Jamaica Street side of the grounds owned by Mr. Lincoln. This house and the land around it were bought by the Archdiocese in 1867. The Boston Directory for 1873 lists Father Magennis as living at that address. The 1873 Bromley Atlas shows the Winkler house added to the existing house.

St. Thomas Aquinas Church entered a building spree between 1886 and 1891 when a new school, convent, and parsonage were built. The bell tower having been built sometime before 1886. In 1886, the home was moved back 75 feet and a second story was added to the old Winkler house, as well as a projecting bay with conical roof facing Jamaica Street. A large four-story addition was added to accommodate sixty Sisters in 1898. This was a broad-faced, brownstone, Ruskinian-Gothic building. Also in 1886, a parsonage was built for Father Thomas and his assistant priests facing South Street at the corner of Jamaica Street. It was a 2½ story, wood-frame house with a mansard roof.

Bellcote, St Paul’s Church, Spalding, United Kingdom. Built in 1878-1880 in a brick Gothic style with stone trim. Very likely what the bellcote at St. Thomas Aquinas looked like. Image from https://sites.google.com/site/stpaulfulney/

Reporting on the foundation ceremony of the Pope Leo XIII School on December 15, 1888, the Boston Globe labeled it "the crowning event of the wonderful progress of St. Thomas parish. Father Magennis sees the fruition of his fondest hopes." The school was dedicated with great ceremony on August 31, 1890 by Archbishop Williams. "The children of the parish including 100 little girls attired in white with veils assembled in the church," reported the Globe on September 1, 1890.

Work began in 1889 on the three-story, wood-frame school capped with a graceful cupola and a central bell tower and cross. It had eight classrooms, community rooms for the parish, a gymnasium, music room and library. The bell was a gift of Pope Leo XIII who also gave permission to use his name on the school.[xxv] For decades the bell was known as the "Voice of Leo." On November 11, 1918, neighborhood children rang the bell announcing the end of World War I.

The school building had eight classrooms, community rooms for the parish, a gymnasium, music room and library. The main hall occupied the entire third floor. It was 29 feet high with an arched, pressed-metal ceiling. The ceiling was divided into panels painted with frescos by Charles J. Schumacher. The center panel of the gallery was decorated with a bronze medallion of Pope Leo XIII, cast by the Italian sculptor Appolloni, and was a gift of Thomas B. Noonan.[xxvi] The total cost for the building was $29,880, about $828,000 in 2019 dollars. The school's enrollment was fifty children ages five to fifteen. The boys entered from Jamaica Street and the girls from St. Joseph Street.

The earliest photograph of the 194-foot bell tower was published in the Sacred Heart Review of May 14, 1892. The bell tower was built before 1886 when the parsonage was constructed. The tower was built off the foundation and walls of the original bellcote. The horizontal sandstone band across the facade of the present building (just above the door) was the location of the tower. The tower was built in four sections, each marked by granite chevrons. The fourth supported an open arched belfry; a tall cylindrical cap topped the structure with a cross on top. This was a rare church design for Keely: a classic Gothic building with a tall, square campanile supporting bells, and topped with an elongated, pointed tower. It was almost like a minaret. The tower had wooden stairs in it to connect to the belfry. Boston – and Jamaica Plain – had seen tall steeples and towers before: the New Old South Church, the Boston and Providence Railroad Station at Park Square, and the Central Congregational Church (1872) in Jamaica Plain with its huge wedding cake steeple set to the side of the front. [xxvii] But St. Thomas Aquinas was the first church for Catholics in Jamaica Plain. The tower was very tall and built of brick, almost twice the height of the church itself. It was different. It was meant to be seen. It was also meant to show that the Irish Catholic had arrived in Jamaica Plain.

Pope Leo XIII School, from Sacred Heart Review, May 14, 1892

In 1898, Father Magennis became aware of deaf children in his parish and it bothered him a great deal. How could they hear the word of God? But more than that, they were ostracized from the rest of society. He sent several Sisters for training in the latest methods of teaching the deaf and set aside rooms in the old Winkler house as classrooms for deaf children. The Boston School for the Deaf was chartered by the State of Massachusetts in May 1899 and opened in October with four students. This grew to 31 students, and 28 students were provided with room and board. In 1905, the school moved to Randolph on a thirteen-acre farm that Father Magennis bought, where a new schoolhouse was built. He remained its superintendent until his death in 1912.[xxviii] The School for the Deaf closed in 1994.

The Convent, showing the 1886 wood-frame enlargement on left and the 1898 stone addition on right. From Centennial History of St. Thomas Aquinas Church, 1969. Archives of the Archdiocese of Boston.

The Catholic population was growing in Jamaica Plain and nowhere faster than in the dense factory-tenement district between Green Street and Egleston Square. In 1895, Father Magennis acquired two lots on Brookside Avenue near Montebello Road, possibly as a gift, or at a reduced price, from Thomas Minton, the contractor and parishioner who owned adjacent lots. On this parcel he built a narrow, wood-frame mission church of St. Thomas Aquinas. The population increased enough so that in July 1908 a separate parish was created there, called Our Lady of Lourdes, under Reverend George Lyons. Rev. Lyons enlarged the existing structure with a rear addition, a belfry, and extra land. The new church had two altars and an illuminated fresco of the Grotto of Lourdes. Father Magennis joined Archbishop William O'Connell in dedicating Our Lady of Lourdes on September 12, 1909.[xxix]

Father Thomas Magennis was elevated to Monsignor in 1896, and died on February 12, 1912, after serving his namesake parish for 44 years. "In the case of Monsignor Magennis, the opportunities to do good were perhaps more numerous than the lot of the average clergyman, and he made the most of those opportunities."[xxx] His funeral mass was said at St. Thomas Aquinas Church, and attended by Archbishop O'Connell and 200 priests; among them Rev. Lyons of Our Lady of Lourdes and the Right Rev. Edward J. Moriarty of St. Peters Church in Cambridge. Among the pallbearers was Thomas Minton. [xxxi] Father Magennis was buried on a hill of Mt. Calvary Cemetery. Either by choice or by chance, the monument of solid granite, supporting a granite cross, faces in the direction of St. Thomas Aquinas Church. He was joined by his "faithful sister" Mary on November 29, 1920.

Original Interior of St Thomas Aquinas Church. Undated photograph. Showing the original stone alter, rederos and chancel, the three big murals and wooden arches; a dark church with a bright white stone rederos and alter. A typical Keely design that focused all eyes towards the altar. Everything was removed in 1914. The mural behind the rederos was replaced by the present stained glass window of St Thomas. The rafters were seemingly plastered over. Saint Thomas Aquinas Church 150th Anniversary, 1869 -1969.

Among the many priests attending the service of Fr. Magennis was Right Rev. Edward J. Moriarty of St Peter’s Church in Cambridge. Born in East Boston in 1856, Rev. Moriarty may have attended one of the two churches Keely designed in that section of the City.

The St. Thomas Aquinas Church that we know today, became the church of Edward J. Moriarty after the death of Fr. Magennis. Rev. Moriarty became pastor of St. Thomas Aquinas in May 1912 and served until 1928. "The second pastor, Rt. Rev. Edward J. Moriarty transformed and beautified Monsignor Magennis' old church so as to give it both within and without quite a new appearance."[xxxii] This was an understatement. The key word was "old." Rev. Moriarty clearly wanted a new and modern look to his church, and with the permission and funds from Archbishop O'Connell, he went to great lengths to achieve it.[xxxiii] Like almost everything about the architecture and renovations of St. Thomas Aquinas, there is no documentation on when this major redesign and reconstruction took place, or who was the architect. There is only one hint about when the work was done. Henry Keaveny, in his 1985 oral history, "A Day in 1920," recalled "looking at the twin steeples of St. Thomas Aquinas Church. Two years ago (1918) it had one steeple much higher [that] contained the bell. It chimed the Angelum three times a day, just as they do today."

Beginning in 1913,the campanile and the entire façade was pulled down and rebuilt with an entirely different design and the interior completely changed by the eminent church architects Maginnis and Walsh. The single campanile was replaced by two octagonal tourelles topped with copper belfries of barrel and spire in Art Deco style. The front façade was pushed out and the four arched windows in a line over the door were replaced by one massive arched window framed in light stone. The glass is opaque; it admits no light because the Hook organ is behind it. [xxxv]

St Thomas Aquinas Church with the original tower. ca 1885 before the parsonage was built in 1886. The Winkler House has been moved to the rear of the lot to make room for the rectory. Saint Thomas Aquinas Church 150th Anniversary, 1869-2019

The interior was completely gutted. The altar, frescos, arched rafters, and reredos were removed and redesigned in a sleeker Art Deco style, with a restrained and spare box flanked by angels and saints in tall niches. The original stone rail was removed sometime after 1969. The frescos were painted over (or possibly removed) when the back wall was redesigned and rebuilt with a new stained glass window. The new window showed Saint Thomas preaching as was created by Thomas Sullivan. The original hand-carved wooden rafters (a typical Keely feature) were replaced, plastered over and painted like the walls in a cream color.[xxxvi]

The Boston Globe of November 1, 1914 described the changes in great detail:

In the reconstruction of the church Mgr Moriarty has spared no effort to make it one of the most beautiful churches of the diocese. The facade…has been almost completely reconstructed and given a marked individual character by means of two octagonal tourelles which frame a great traceried [ early Irish Gothic] window. Entering the auditorium one is astonished to see no trace of the original architecture… the complicated and dingy character of the former entrance has been changed to a brightly lighted and roomy foyer. The windows of the aisles have been raised and given a pointed Gothic character.

It should be noted that Charles Maginnis, the chief architect of the firm, who himself designed many Catholic churches, was not fond of Keely’s work. The statues of St. Patrick and St. Thomas were removed. A new stained glass window of St. Thomas was set above the reredos showing the Saint teaching. This window replaced the original large fresco. The plaque to Abner Child was also removed. Keely's church was gone. All that remains are the supporting arches, the stained glass, and the Stations of the Cross.

The new church was rededicated with great ceremony by Cardinal O’Connell on November 1, 1914. As reported by the Boston Globe on November 2, 1914 the Cardinal explained the reasons for the redesign. “It is not enough to erect a structure - it must be cared for and from time to time if necessary renovated [and be] properly and beautifully preserved according to the growing needs of the people and the time. Rev. Michael Scanlon went further in his sermon: The old church was literally worn out in God’s service. It had been used by day and by night for years. Rebuilt, renewed, readorned, this church stands as proof that the faith in your midst is still strong.”

The interior redesign was continued under Rev. William J. Casey, the fourth pastor who came to St. Thomas in 1935.[xxxvii] About 1937 two wooden statues of The Virgin and Joseph the Carpenter were set on the flanking pillars nearest the altar. These were done by skilled but unknown artisans.

In June 1926, architect Matthew Sullivan (who had been a partner with Maginnis and Walsh until 1905) completed his design for a new high school at 19 St. Joseph Street. This high school building replaced eight wood-frame, three- and six-family homes. these had been built by the church between 1890 and 1905, for investment income. The St. Thomas School Society bought the land in two parcels. The houses were either moved or razed. A three- story addition to the school was completed about 1937, likely designed by Sullivan.

While the church of Patrick Charles Keely and Father Thomas Magennis was gone, the parish flourished in the new church. And the neighborhood changed. The public works yard moved to Forest Hills Street in 1954 and the Church used the city lot for parking. Farnsworth House was built there in 1982. In August 1953, the 3.5-acre streetcar barn and tracks, dating as far back as 1858, were replaced by twelve buildings of the South Street Apartments developed as state-funded public housing. The MBTA (or MTA as it was known at the time) owned the streetcar yard and moved it to the Arborway yard in 1949. The streetcar barns were razed in the 1930s, but trolley buses and motor buses used the lot for the Dudley Square line until 1949.

St. Thomas Aquinas Church celebrated its centennial with great enthusiasm in 1969, but times were changing. In December 1972, the Sisters of St. Joseph announced they would cease teaching due to the decline of membership in the Order. This threatened the closure of 24 schools across the Archdiocese. Parents paid $6 a week for each child to attend the grammar school, which closed in June 1973. In 1973, parents unsuccessfully sued the Archdiocese to keep the St. Thomas High School open, and the last class graduated on May 30, 1975.[xxxviii]

Father John C. Thomas – also born in Lowell, and also with same name as the church – was appointed pastor during the middle of this tension in 1974. In his obituary, The Pilot wrote that "times were changing and Father Thomas met those changes."[xxxix] Father Thomas closed the High School and the convent. The Pope Leo XIII School was razed by 1977 and made over into a parking lot. The high school building today serves as the Nazareth Family Center, an early childhood care facility owned by Catholic Charities. It relocated to this location in November 1987 (coming from 420 Pond Street). What happened to the Pope Leo XIII bell and medallion is unknown; the Archdiocese has no record of them.[xl]

On March 1, 2011, St. Thomas Aquinas became the headquarters church of the combined parishes of Our Lady of Lourdes and St. Mary of the Angels. Rev. Alonso Machias was the first pastor of the combined parish.[xli]

On a rainy Sunday (November 24, 2019) Sean Cardinal O’Malley and Rev. Carlos Flor, successor to Fr Thomas Magennis celebrated the 150th anniversary mass. The sanctuary was filled with parishioners old and new.

A photo gallery of contemporary images related to this article may be found here.

By Richard Heath

June 2019 | revised and corrected in January 2020 and October 2021

Editorial assistance provided by Jenny Nathans and Kathy Griffin. Formatting assistance from Charlie Rosenberg and Gretchen Grozier.

[i] Robert H. Lord et al., History of the Archdiocese of Boston in the Various Stages of its Development, 1604 to 1943 (New York, 1944), vol. III, p. 627.

[ii] Dorchester and Hyde Park were also separate towns.

[iii] St. Thomas Aquinas Centennial, 1970. No author.

[iv] Centennial, 1970.

[v] Lord suggests that this was done begrudgingly; but given the welcome to Fr. Magennis, this was probably less out of Catholic bigotry than because of the argument about the separation of church and state.

[vi] Centennial.

[vii] Named after the famed mathematician Nathaniel Bowditch, whose kinsmen lived in Jamaica Plain. It was replaced by the new Bowditch School on Green Street in 1892. The site then became the City of Boston public works yard. The plows, trucks, wagons, drays, barns and garages remained until 1954. The streets and sidewalks around St. Thomas were undoubtedly well cleared in winter.

[viii] Jamaica Street was laid out in 1850.

[ix] Richard J. Purcell, "P.C. Keely: Builder of Churches in the United States," in Records of the American Catholic Society of Philadelphia, Dec. 1943; and Francis W. Kervick, Patrick Charles Keely, Architect; a Record of his Life and Work (South Bend, Indiana, 1953).

[x] Demolished in 1957, but by then it was unrecognizable – ironically, a fate shared by St. Thomas Aquinas Church.

[xi] Still standing and on the National Register. John F. Kennedy was married there in 1953.

[xii] This firm designed St. Margaret's Church on Columbia Road, St. Angela's, St. John's, and St. Hugh's churches on Blue Hill Avenue. St. John's Church was demolished.

[xiii] He was buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Brooklyn. No headstone remains today.

[xiv] Centennial.

[xv] Boston Globe, July 22, 1888.

[xvi] Named not for Fr. Thomas Magennis, who seems to be forgotten, but for Fr. John Thomas, the pastor from 1974-2000.

[xvii] Boston Globe, July 22, 1888.

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] This person is apparently lost to history; no reference has been found for him.

[xx] Sacred Heart Review, May 16, 1892.

[xxi] Boston Globe, July 22, 1888.

[xxii] The other pre-Civil War Hook organ is at the First Church in Jamaica Plain, Unitarian Universalist. Organ Historical Society, OHS Pipe Organ database, and Roger Lovejoy, St. Paul's Cathedral, letter to author, May 20, 2019.

[xxiii] Centennial. The plaque is gone.

[xxiv] Sisters of St. Joseph web site: https://www.csjboston.org/who-we-are/celebrating-144-years-and-beyond/, and Mary Glynn, "Parochial Education in Jamaica Plain," JPHS archives, 1989. Sr. Mary Regis was 30 years old when she arrived; she died in 1917 at age 74.

[xxv] In a letter to Fr. Magennis, February 4, 1889. The letter has not survived.

[xxvi] "Sacred Heart Review," May14, 1892; Boston Globe, July 22, 1888 and September 1, 1890.

[xxvii] This church burned in 1934 and was replaced with the more conventional Colonial Revival church with a white, center steeple. The well-known ecclesiastic architect Edward T. P. Graham used the campanile design more successfully in his plan for the Church of St. Paul on Mt. Auburn and Arrow streets just outside Harvard Square, built in 1916-1924.

[xxviii] Boston Globe, January 14, 1906, with thanks to Mark Bulger.

[xxix] Boston Globe, September 13, 1909, with thanks to Mark Bulger. The present-day Our Lady of Lourdes Church on Montebello Road was dedicated on Thanksgiving Day 1931. Designed by Edward T. P. Graham in full-blown Art Deco style, it is one of Graham's best churches.

[xxx] The Sacred Heart Review, March 2, 1912.

[xxxi] Thomas Minton (1847-1916) was largely responsible for the development of Forest Hills. He emigrated from Ireland at age 17 in 1861 and began work as a contractor building roads before turning to real estate.

[xxxii] Lord et al., History of the Archdiocese of Boston, Vol. III, p. 617.

[xxxiii] William Cardinal O'Connell was also born in Lowell (1859) and was known as an imperious and autocratic church noble. Nothing happened in the Archdiocese without his permission until he died in 1944.

[xxxiv] Charles Maginnis (1867-1955) was born in Ireland and also worked for Wheelwright. His partner Timothy Walsh (1868-1934) worked for Peabody and Stearns. If there was a successor to Keely of Catholic church architecture in the United States it was Maginnis and Walsh.

[xxxv] Keely's first church design in Williamsburg (New York) dedicated in 1848 had the same fate. Its 150-foot tower and steeple were pulled down and a new Baroque facade of spindles, pitched roof, and wide doorways was built of light stone in 1902. The architect was George H. Stratton. Keely's church was gone. The whole building was torn down in 1957.

[xxxvi] The frescos likely could be seen if the overpainting were removed. The altar, reredos and statuary were likely donated to another church. At some point after 1969 the original stone rail was removed.

[xxxvii] Rev. Casey served until his death in 1949. The new Arborway bridge (since demolished) was named in his honor in 1951.

[xxxviii] Boston Globe, Dec. 13, 1972; Dec 16,1972; Jan. 11, 1973.

[xxxix] The Pilot, April 13, 2007.

[xl] Ashlyn Rickford, archivist of the Archdiocese of Boston, in a message to the author on June 6, 2019: "It doesn't appear that we have a record of the bells in storage. I'm not sure if these were destroyed or moved to another building. Typically, plaques and stained glass are destroyed. Statues and other decorations are given to other parishes."

[xli] Jamaica Plain Gazette, March 4, 2011; May 8, 2012.

Patrick O’Connor has also graciously provided his written history for the 150th anniversary of St Thomas Aquinas as well as a List of the Pastors and Priests from 1869-2019