Boston's Lost Breweries

The Burton Brewery, Parker and Health Street. Courtesy Boston Public Library.

Beer making in Boston was in its heyday in the early 1900’s. Try to imagine the clatter of horse-drawn, iron-wheeled, wagons bringing raw materials in and finished product out of the 24 breweries in Roxbury and Jamaica Plain which were located on or near Columbus Avenue, Heath Street and Amory Street. Add the pungent odors of hops, yeast, slowly cooking grains and the coal and wood smoke billowing from each of the 24 smokestacks and you begin to sense the impact these breweries had on their neighborhoods.

And why were they located here? There are two simple reasons: abundant and crystal clear water from the aquifer along the Stony Brook along with artesian wells bubbling to the surface around Mission Hill; and the relatively cheap land after the City of Roxbury merged with Boston in 1868. These conditions, combined with the demand for the new German type Lager beers, drove the expansion of the industry locally.

The Stony Brook originates in the Stony Brook Reservation in Hyde Park near the highest part of Boston and it flows from there to the Muddy River, terminating behind the Museum of Fine Arts in the Fens. In the early 1900’s Stony Brook was enclosed within a large culvert that straightened-out the old meandering route as it passed through Jamaica Plain and Roxbury. The top of the culvert lies very near the surface of the land; thus one can trace the route of the culvert by the absence of construction over it along a straight line from Cleary Square, in Hyde Park, to its terminus in the Fens. Another marker for its location is the rail corridor for the Orange Line and Amtrak trains which parallels the culvert’s path.

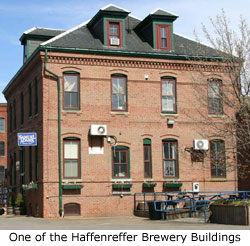

Today many of the old main brewing buildings are gone but some of the ancillary buildings are still in place. Most of the remaining buildings are in rough shape having been idle for long periods since the beginning of Prohibition in 1919. after the repeal of Prohibition in 1933 there followed a short period of growth by the five that reopened, but they were overpowered by the giant national breweries. Only one of the 24 breweries; Haffenreffer’s, remains active at this time, as we shall see.

Boston, with a total of 31 breweries, was distinguished as the city with the highest number of breweries, per capita, in the United States. The 24 located in our area were very close together, within a circle of about a mile and a half. Sometimes they were located right across the street from each other, and sometimes there were three in a single block! Traveling down Columbus Avenue one passes seven former brewery sites in just a few minutes. This density of breweries was also a very unique circumstance at the time.

Let’s visit some of the remaining brewery sites and review their places in Boston’s lost brewing history.

A.J. Houghton & Co. “Vienna” Brewery

Located at Station and Halleck Streets, it was active from 1870 to 1918. It occupies the site of the old Christian Jutz brewery built in 1857.

The Vienna Brewery had originally been located across the street where it was owned by Messrs. Houghton and Cole of Maine and Vermont. They bought the Christian Jutz property and moved their main operations across the street, converting their original property to a stable to house their several transport horses. Here they produced Vienna Lager from a German recipe. The lighter German and Austrian Lager beers came into favor in the 1850’s and 60’s displacing the heavier English/Irish Ales. Besides Vienna Lager, they made Pavonia Lager Beer, Vienna Old Time Lager and Rockland Ale.

This is the only landmark brewery in Boston, having been protected by the Boston Landmarks Commission, despite its poor condition. It had a five story main brewing building with a large cupola, an office building, three storage buildings, a coopering or barrel-making building, and a power plant. It was a beautiful building with brick used for architectural features instead of stonework or terra cotta. The sweeping arches are built of brick while the sills and parts of the arches are granite. The floor joists are supported by architectural ironwork. The exterior “X” shaped elements on the sides of the buildings are iron brick-ties that support the brick bearing-walls and were common design features at that time. They were often connected by long interior iron rods, spanning between the walls, to help hold the structure together under the floor loads of several stories.

The main brewing buildings had robust hoists and pumps to lift the grains and water up to the top floor to begin the brewing process. Gravity would then take the brew down to the various levels and processes below. This, then, was a “vertical” brewery. When pumping technology improved, the vertical process was discontinued in favor of the “horizontal” brewery with lower buildings and other efficiencies. This brewery closed when Prohibition arrived in 1919 and it never reopened on a full-scale basis.

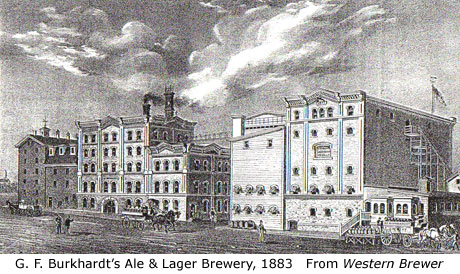

Burkhardt Brewery

Moving now to Station and Parker Streets we come to a large parking lot which is the former site of one of the largest and best known Boston breweries, the Burkhardt Brewery, active from 1850 to 1918. Mr. Haffenreffer, whom we’ll hear more about later, began his career here and became Burkhardt’s brewmaster.

Burkhardt built two large six-story Roxbury Puddingstone buildings and a large stable forming an L shaped enclosure around the adjacent Houghton and Company Vienna Brewery. Gottlieb, or George Burkhardt and his son, Gottlieb Jr., ran the brewery until Gottlieb Senior died in 1884. It continued brewing until Prohibition closed it in 1919. It stayed open, however, until 1929 producing cereal and other grain products during the dry period. Burkhardt made both beer and ale. Their labels were Tivoli Beer, Extra Lager Beer, and; starting in 1912, Red Sox Beer, to honor that year’s World Series Champions. They also made Augsburger Lager & Augsburger Dark, Salvator Lager, Brown Stock Lager and Bock style Lager. They produced over 100,000 barrels a year of beer alone, plus Golden Sheaf Ale, Cream Ale, Brown Stock Ale, Old Stock Porter, India Pale Ale and; also starting in 1912, Pennant Ale.

Postcard image of Burkhardt Brewery wagon, 1912

Most of the skilled brewery workers were Germans and Austrians. Other skilled crafts included mechanics, boilermakers, steamfitters, coopers, stablemen, teamsters, ice handlers, etc. Gottlieb Burkhardt Senior lived directly across the street from his brewery. Wentworth Institute, who planned to put a hockey rink here until it was made a Boston Landmark, presently owns the building.

McCormick Brewery, Hanley and Casey, and Continental Brewing

There were three breweries located where the present Mission Housing Development now stands; McCormick Brewery that brewed Fenway Ale, the Hanley and Casey Brewery and Continental Brewing, also known as Frey & King.

Now moving through the Mission Hill neighborhood on Parker Street the first house on the right was Mr. Hanley’s. The adjacent three-deckers housed German and Irish brewery workers employed in the area’s dominant industry. The nearby Holy Trinity Church served a German-speaking congregation that continues to this day in Jamaica Plain. The original church is the small aluminum clad building on the site. It was originally called the Elliot Mission, named for John Elliot of Roxbury. The new church was built by a German-American architect named Jacob Luippold.

H. & J. Pfaff, Roessle, and Habich “Norfolk” Breweries

Active from 1857 to 1918, the Pfaff Brewery was located at 1276 Columbus Avenue, the present site of Roxbury Community College. Mr. Pfaff lived next door to Mr. Hanley on Parker Street and could easily walk to work.

Looking across Stony Brook Valley the white house with the cupola is 47 Center Street, the former home of brewmaster John Roessle, who owned the Roessle Brewery at 1250 Columbus Avenue that was active from 1846 to 1918 and from 1933 to 1951. It too was on the Community College site. A third brewery, Habich “Norfolk” Brewery, active from 1874 to 1902, was located at 171 Cedar Street and occupied the same College site. Habich was the first Boston Brewery to make Lager beer in the 1850’s.

The Stony Brook culvert sits very close to the surface of Terrace Street, the home of two very productive breweries. The Union Brewery, active from 1893 to 1911, was located at 103 Terrace Street. It produced only German Lager beer. It had a large six story, arched, main building and two smaller buildings housing a stable and a powerhouse. The two smaller buildings and the mural-decorated smokestack, which now also does duty as a cell phone tower remain. The former stable is now Mississippi’s Restaurant.

Nearby, at 94 Terrace Street, the Park Brewery, active from 1881 to 1918, produced only Irish Ales. One building, now Frank’s Auto Body Shop, remains on the site. The wood siding on the building covers the original brick. In the rear, the remains of a granite block embankment still exist. Most of it was removed for the Orange Line construction project. James W. Kenney owned both breweries. It’s thought that the different yeasts used in beer and ale production is the reason Kenney separated the two processes.

Now we come to the Rueter & Alley “Highland Spring” Brewery, active from 1867 to 1885, located at Heath and Parker Streets. This was a five or six-story magnificent building with a beautiful little arched refrigeration building built in 1895, and a bottling building. Before artificial ammonia refrigeration was developed in 1884, natural ice from the ponds around greater Boston was used to cool the beer after brewing and during the aging process. The artificial refrigeration plants that nearly all breweries installed made ice for the purposes stated and thus displaced the ponds as the source of ice.

Driving down Columbus Avenue one can still see “Highland Springs Ale” painted on the outside of the building. Rueter produced Irish style ales and it was the largest ale and porter brewery in the United States in the 1870’s. In 1876 their ale won a coveted gold medal at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, despite Philadelphia’s claimed leadership in brewing ale.

When Alley left to start his own brewery on Heath Street, the name was changed to Rueter & Company and continued under that name from 1885 to 1918. Rueter was President of the United States Brewers Association for many years. His estate was on the Jamaicaway where Jamaica Towers is presently located.

This plant closed in 1919 and was thereafter used as a warehouse by Oliver Ditson Company, the Boston music-publishing firm. Croft Company, making Croft Ale, remaining active from 1934 to 1953, reopened it as a brewery after Prohibition. Mr. Croft had been a brewmaster for Rueter and Alley. One of the buildings stayed active until recently as Rosoff Pickle factory until it was bought by Hebrew National Co. and moved to New York.

Highland Springs, John R. Alley, American Brewing Company, Burton and Roxbury Breweries

Leaving Stony Brook and traveling along Heath Street we come to the Highland Spring Brewery. Highland and the other Heath Street breweries drew their water from artesian wells beneath Mission Hill, instead of the Stony Brook aquifer. The wells have been capped to allow conversion of some of the old brewery buildings to housing and studios.

Next comes the John R. Alley brewery that Mr. Alley started when he left Rueter and Alley. Located at 123 Heath Street, it was active from 1886 to 1918. It was designed by Otto Wolf, a Philadelphia Architect, in 1886. It is a seven bay building with 3 arched bays either side of the main carriage entry bay. The brewing was done in the left set of bays. This displays a beautiful use of brick and granite with half the granite polished and half left rough in a handsome checkerboard pattern. You will still see the owner’s initials, JRA, carved over the employees’ entrance. Note also the metal carriage blocks in the carriage entry that would prevent a broken wheel should a carriage negotiate too tight a turn coming in or leaving. The smaller brick refrigeration building was built in 1899.

The Alley brewery was also known as the “Eblana” brewery because it produced “Eblana” Irish Ale; Eblana being the Greek word for Dublin. Frederick and George Alley took it over in 1898 when John R. died. It continued operating until Prohibition. During and after Prohibition it was a Canada Dry Ginger Ale bottling plant.

We come now to the American Brewing Company at 235 - 249 Heath Street. It was active from 1891 to 1918 and from 1933 to 1934. James W. Kenney whom we met earlier at the Park and Union breweries owned it. The brewmasters were Gottlieb, Gustav and Gottlieb F. Rothfuss, all of Jamaica Plain.

This is undoubtedly the most handsome of all the remaining breweries in Boston and once can see at a glance the pride the owners had in the place, the process and the product. The architect was Frederick Footman of Cambridge. It was built in three phases, with the oldest part on the left, the second one with the American Brewing Company name came next and then the third wing with the beautiful granite arches and terra cotta heads which was the office complex emblazoned with the initials ABC. The granite was probably either Chelmsford or the slightly grayer Quincy.

American Brewing Company, 251 Heath Street, Jamaica Plain, 1930. Photograph courtesy of Nick Shields.

Still visible in the main, or brewing, building is the large overhead access shaft where the malted barley and water were lifted to the top floor with hoists and pumps. The barley was stored in cedar-lined rooms in the top two stories of the main building to prevent insect infestation. The brewing process was started there as the grain was cooked. The cooked mash then flowed to the floor below where the grain was removed as waste and hops and other ingredients were added to the residual brew, along with the yeast that triggered the fermentation that produced the alcohol. The final product was then stored in temperature-controlled areas at the lowest level. Also still visible in the lower level is the capped wellhead that had delivered countless thousands of gallons of pure Mission Hill spring water to the process.

A wonderful touch of the spirit of the times is the “customer” room in the basement. Customers were entertained here in a room with walls, ceiling and floor painted with German drinking slogans, flowers and other reminders of the source of the Lager recipes. The offices had beautiful arched, semi-circular windows with stained glass. The tower is rounded and has a clock fixed at seven and five, the workers’ starting and quitting times. It also has granite carriage blocks to protect carriage wheels from breaking if too tight a turn were attempted when entering or exiting.

During Prohibition it was used as a laundry. After 1934, Mr. Haffenreffer used it for a time as a second brewery. Most recently it was used by a fine arts crating and shipping company, the Fine Arts Express Co. It is presently being converted to housing units.

At the opposite end of Heath Street, near General Heath Square, we would have seen the small Burton Brewery on the site now occupied by the Bromley-Heath Housing complex. It was owned by J. K. Souther who produced Burton Ale, Bull’s Head and Special Porter. During Prohibition it bottled a soft drink called Moxie, — which was definitely an acquired taste; but more importantly, the genesis of a new word in the American lexicon. Moxie is the oldest continuously manufactured soft drink in America starting in 1884 in Lowell, Massachusetts and it is still available from on-line vendors.

Nearby, the small Roxbury Brewing Company at 31 Heath Street was also built by Frederick Footman. It was active from 1895 to 1899 and was owned by William G. Titcomb of Providence. Its short life was due to under-capitalization. Rueter & Company bought it and produced 125,000 barrels a year there.

Robinson, Franklin, Haffenreffer and Sam Adams Breweries

The ubiquitous James W Kenney appears now in Jamaica Plain where he buys the Robinson “Rockland” Brewery at 55 - 71 Amory Street. It was active from 1884 to 1902. The building and smokestack still stand. Mr. Robinson, the former owner, ran the brewery for Kenney producing Elmo Ale, named for Robinson’s son. The building later became Trimount Tool Company. It is now a Futon factory with residential artist’s lofts.

Traveling along Amory Street one passes the former sites of many diverse industries including electrical, japanning and lacquering, electro-plating, silver-plating, leather tanning, rubber, and junk yards; none compatible with brewing beer. Reflecting this diversity, the former names of nearby Cornwall and Brookside Streets were Cooper Street and Chemical Avenue. There were many brewery employees’ homes located here along with several German social and cultural clubs. They served the nearly 14% German-American population in the area with places to gather socially and preserve their strong ties to the old country.

At 3175 Washington Street we find the handsome Franklin Brewery; named for nearby Franklin Park, and rivaling ABC Brewery in architectural beauty. It was active from 1894 to 1918. Its beautiful façade was hidden from view by the elevated railway from 1912 until 1988. The initials FPC can now be seen at the 4th floor. It was a vertical brewery with six stories above Washington Street and nine stories above Haverford Street in the rear. Carriages couldn’t turn around in the yard and had to pass through and exit via a ramp in the rear. It was built by Chicago architect Charles Kaestner who cleverly fools the eye with arches designed to make the building look symmetrical, when in fact it is unbalanced. They produced 40,000 barrels of ale per year, including the XXX (Triple X) Ale and Stock labels. After 1918 it became home to various moving and storage companies. D.W. Dunn Co was located here as well as Larkin and Sons Storage Warehouse.

Now we come to the Haffenreffer Brewery at Bismark and Germania Streets. It was active from 1870 to 1964 and reigned as queen of the Jamaica Plain fleet of breweries. Rudolph Haffenreffer had been brewmaster at Burkhardt’s brewery and had married Burkhardt’s niece. He then left Burkhardt’s and started his own brewery which was to become the last operating brewery in Boston.

It was a 14-building complex with a tower building, main brewery, storage building, paymaster’s office, stables, and an extensive bottling plant, etc. A widely believed local rumor places a spout in the main brewery wall delivering free beer to any and all visitors. The buildings had slate roofs, one of which was an odd, trough-shaped, affair designed to catch and funnel rainwater to the power plant. Underground steam pipes connected many of the buildings, including Haffenreffers’s house next door at 21 Germania Street. This is a good example of the vertical and later horizontal brewery with the lower buildings and other efficiencies gained in that process. After closing in 1964 it was a storage warehouse including garages and artists’ accommodations as well. Now owned by the Jamaica Plain Neighborhood Development Corporation it counts among its tenants several food operations and the famous Sam Adams Micro-Brewery that was started in 1988. Regular tours are conducted at Sam Adams and one can once again see beer brewing in Jamaica Plain in a building that just won’t quit.

Conclusion

In this survey of Boston’s lost breweries we’ve seen how a thriving local industry prospered, expanded and then abruptly died under a well intentioned, but impractical law. Fortunately, however, the lost breweries have left us with several beautiful buildings and diverse Jamaica Plain neighborhoods still enriched by the ethnic and cultural roots of the people who came here to work in them.

Additional Resources

A collection of Boston brewery posters has been placed on line by the Boston Public Library via their Flickr site at http://www.flickr.com/photos/boston_public_library/

We have provided links to a selection of those images:

American Brewing Company

This article is based on a tour given by Michael Reiskind on March 25, 2006. Peter O’Brien transcribed and edited the material from tape. Modern photographs by Charlie Rosenberg. Copyright © 2006, Jamaica Plain Historical Society.