JP High School and the Stay Out for Freedom School Boycotts

The 1960s saw dramatic struggles for civil rights in the southern United States. Efforts to desegregate lunch counters, intercity buses, and schools drew the attention of the nation. African Americans participating in non-violent protests had rocks thrown at them, food dumped on them, dogs and hoses turned on them, suffered beatings and worse. Campaigns to help register Black voters resulted in the deaths of both Black and White volunteers.

In Boston, African Americans were struggling for civil rights as they were in other parts of the country. In some neighborhoods, racist threats toward African Americans were common. Parents and other community members were inspired to push for better access to education in the Boston Public Schools by using some of the tactics that were being used in the southern states such as boycotts and sit- ins. [1]

Parents and community members hold sit-in at the June 11, 1963, Boston School Committee meeting Boston Globe Library collection at Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections

NAACP pickets Boston School Committee August 1963, Northeastern University

Boston Public Schools in the 1960s

Black parents and other Boston community members spent years documenting conditions and presenting evidence of the need for change in the Boston schools throughout the 50’s and 60s. They reported inequality in curriculum, spending, and facilities. The quality of schools was uneven. Predominantly Black schools were overcrowded, the buildings were old and dilapidated. Many had a higher percentage of substitute teachers and very few African American teachers. [1, 3] Boston Public Schools (BPS) administrators claimed that there was no deliberate segregation, but at the same time gave fewer resources to schools that were mostly African American. Several of those advocating for reform in the BPS ran for school committee—Ruth Batson in the 1950s and Mel King and Nathaniel Young in 1961—but were defeated. [2] Mel King ran for the Boston School Committee a total of three times.

1963-64 Freedom Schools in Boston

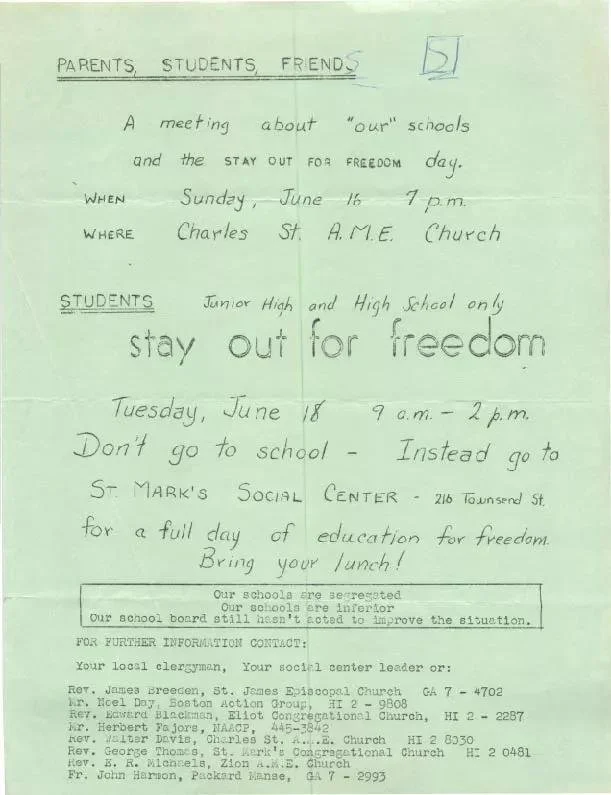

Finally, some leaders decided to take decisive action. Other northern cities had been planning school boycotts for a while—New York, Milwaukee, Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland. Boston was part of this group and had worked with the other cities to implement “stay outs” and “freedom schools.” After months of organizing meetings and with the help of area churches, 3,000 African American junior and senior high school students stayed out of Boston schools on June 18, 1963. Instead of attending their public schools in Boston 1,500 of them participated in freedom schools located in churches or community centers. Students learned lessons in Black history and civil rights struggles and sang freedom songs using a curriculum similar to that used in the freedom schools of the South. Star Celtics player Bill Russell attended as did students from local colleges. Russell told students at the St. Mark’s Freedom School, “We’re ready; we’re into the fight now and I think we’ll win.” The Boston School Department and some African American leaders opposed the boycott, but it was widely regarded as successful. [1] All of the freedom schools were located in Roxbury, the South End, and Dorchester.

Freedom Stay-Out button (photo by Charlie Rosenberg)

Flyer for organizing meeting, Stay Out for Freedom June 1963 (Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections)

Leaders of the boycott decided to hold another one the following year but on a much larger scale. There was some discussion of making it part of a larger movement that would include economic and housing issues. [3] On February 26, 1964, 20,000 African American students stayed away from their regular schools and 10,000 of those attended Freedom Schools that day. It was known as the “Freedom Stay-Out.” Boston students were joined by many others from around the region as well as adults. Most of the visitors were White and came from towns such as Lynn, Lincoln and Newton [1] The goal for the stay-out that year was to show Black and White students learning together in harmony.[3]

Jamaica Plain High in the 60s

How did the boycott impact BPS schools in Jamaica Plain?

In the early 1960s, most of the population of Jamaica Plain was White. Jamaica Plain High School, located at that time at 41-73 Elm Street, was also majority White, but the proportion of Black students was growing each year. [4]

Students from both JP High and the Curley Junior High (which later became Curley K-8 School) attended the freedom schools in 1963 and 1964. In January 1963, the new chairman of the Boston School Committee said “We do not have a problem with inferior schools. But we have been getting an inferior type of student.” [1, 3] Here is what one JP High student, Ramona Baker, said in response:

“And to the Chairman of the School Committee, I say that the only reason there are inferior children is because we have to go to inferior schools, and there we get an inferior education.” Baker also said she thought it was a good idea to have students of different races learn together so they could get to know each other.[3]

Participating in the 1963 Freedom Schools and 1964 Freedom Stay-Out were several African American students who had started attending JP High when their local high school, Roxbury Memorial, was closed. These students, who would have gone to the now-closed Roxbury school, had to choose another one to attend, and some chose Jamaica Plain High School. They traveled from their homes in Roxbury to the school on Elm Street. For the most part they remember positive experiences at the school—they were active in sports and other activities, and received a good education. [4,5]

But there were incidents of racism, mostly outside of school. One of these led to the creation of the Grievance Committee at JP High. Gregory Dunham, who graduated in 1964, tells the story. “Boys who participated in sports had to sometimes walk down Elm Street and then Green on their way to White Stadium. One time, a young man who had previously been a student at JP High and was known to the athletes walking down the street came out of the bar on the corner of Elm and Green. He made a point of knocking into the JP High students as they walked by and called Greg the N-word. A fight ensued, more bar patrons came out to participate and bottles were thrown.” [4]

Fortunately, no one was seriously hurt, but the principal of the school approached Greg to ask how the school could stop future conflicts before they began. They decided to create the Grievance Committee so that Black students could bring their complaints to the school administration directly. Many of the student efforts focused on advocating for Black faculty to be hired and increasing Black student representation on school committees. The students were successful in getting a coach they had known at the Timilty Junior High hired as basketball coach. Fred Gumbs became the first Black head basketball and football coach in the city at Jamaica Plain High School. [4]

Grievance Committee, JP High School yearbook 1964

Prom picture. JP High School yearbook 1965

Mass Racial Imbalance Plan for Boston

Truly equitable quality education for all students is a struggle that has continued for many years in Boston. Immediately before the 1963 boycott, Ruth Batson and others presented a list of 14 demands to the School Committee. Nine of the demands focused on improving the school system in general, asking for things such as intensive reading programs, more counselors, and smaller class sizes. Four demands were for educational equity such as providing more relevant curriculum for their children and looking into why there were no African American principals. The primary demand was for recognition from the School Committee that the school system was largely segregated. The School Committee refused to agree to that primary demand. [2,3, 6]

Following the 1964 boycott, the state formed a commission on racial imbalance which released a report confirming that racial imbalance was harmful to all children. Vernon Carter, a Lutheran minister, held a vigil outside the Boston School Department Headquarters for 114 days until finally the Massachusetts Racial Imbalance Law was adopted in 1965. [2] The law allowed the state department of education to withhold state aid if a school district did not desegregate its schools.

However, the Boston School Committee refused to abide by the state Racial Imbalance Law. Finally, in 1974, the Morgan v. Hennigan case led to the decision to require busing students to other neighborhoods to achieve racial balance within schools. [2] Other efforts by the African American community to improve schooling for their children eventually included the Exodus and METCO programs in 1964 and 1966, which allowed Black children from Boston to attend schools outside their neighborhoods or in the suburbs. [3]

Operation Exodus was a program created by the African American community which sent students from public schools in Roxbury to other schools within Boston and outside the city which were considered better than the schools the children were currently attending. It operated from 1964 until 1969. The Metropolitan Council for Equal Opportunity (METCO) program started in the late 1960s and bused students of color from Boston to schools in many surrounding towns. The suburban towns pay the costs of educating the Boston students with help from the state. METCO continues as of 2025 and includes students from Asian and Latin American backgrounds.

Reverend Vernon Carter leading protest against school segregation outside Boston School Committee headquarters, May 1966 Boston Public Library (courtesy of Digital Commonwealth)

Efforts Toward Equality in BPS Continue

In 1974 federal judge Arthur Garrity ruled in favor of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in its suit against the Boston School Committee, saying that the school committee had “knowingly carried out a systematic program of segregation and …maintaining a dual school system.” This article is being written 50 years after the decision to implement busing to achieve racial balance. In retrospect, the resources put into school desegregation could have gone a long way toward improving all schools. Today’s Boston student body is made up predominantly of students of color, and there is still wide agreement that conditions in many Boston schools are not equitable. Public school advocates must wage a constant battle to push for equity in decision making by administrators to ensure equal facilities and opportunities.

In preparing this article, Fran Perkins of Hidden Jamaica Plain interviewed four people who graduated from JP High in 1964 and 1965: Dr. Gregory Dunham, Dr. Albert Holland, Dennis Lloyd, and Barbara Fields. They have all gone on to distinguished careers in education, business, industry, and other fields. In addition, she conducted two in-depth interviews with Dr. Gregory Dunham and Dr. Albert Holland. Dr. Gregory Dunham became an engineer and worked training others in industry. He also became a teacher and eventually a school principal. He said that it was a “bold move” to leave school during the boycotts and attend the Freedom School. He noted that he did not think as a young man that he would ever be an educator and credits the school walkouts and later civil rights efforts with inspiring him to do so. Dr. Albert Holland was a highly regarded BPS administrator and educator for many years. Boston’s Burke High School was renamed in his honor in 2024. He described his experience at JP High: “It was a model of integrated education. They could have used what happened at JP High in the 1960s to create the conditions that would have worked to integrate all the schools.”

Source: 1964 and 1965 Jamaica Plain High School yearbooks

End Notes

[1] Audrea Jones Dunham, Boston’s 1960s Civil Rights Movement: A Look Back Stay out for Freedom 1963 WGBH Essay Open Vault (WGBH Educational Foundation, 2020)

2] Jim Vrabel, Boston School Desegregation timeline compiled from When and Where in Boston: A Boston History Database.

3] Alyssa Napier, Boston Freedom Schools as places of possibility for reciprocal integrated education History of Education Quarterly Volume 63 Number 1, Cambridge University Press 2023

[4] Interview with Gregory Dunham, January 16, 2025

[5] Interview with Al Holland, March 4, 2025

[6] Black Education Movement in the 20th Century National Park Service Boston African American National Historic Site

Note on the Authors: Hidden Jamaica Plain

https://www.jphs.org/hiddenjamaicaplain

Note on Terminology

https://www.jphs.org/noteonterminology