Woodbourne and the Boston 1915 Movement

A STUDY OF THE PERIOD OF POLITICAL AND SOCIAL HISTORY OF BOSTON IN WHICH WOODBOURNE WAS CONCEIVED AND BUILT AND WHY THE SUBDIVISION CHANGED SO DIFFERENTLY IN ARCHITECTURAL STYLE AFTER 1922.

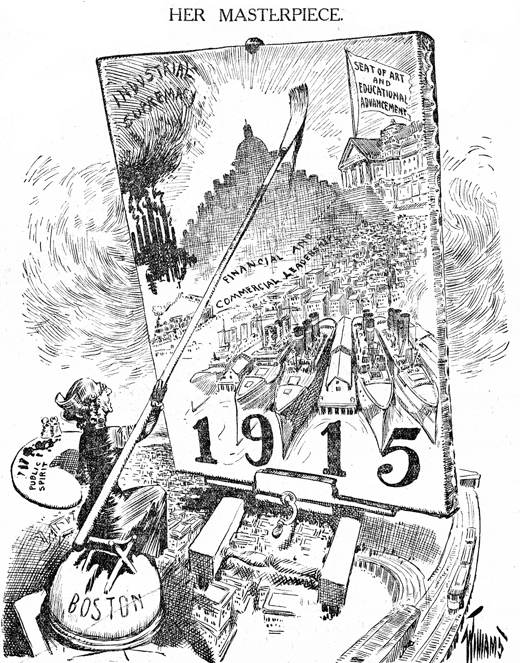

High Mass Progressivism: The business-led Boston 1915 Movement perfectly promoted in this front-page editorial cartoon. Woodbourne was conceived out of Boston 1915 and was one of its most lasting achievements. Boston Sunday Herald, April 4, 1909.

The planning and construction of the first phase of Woodbourne took place during a period of time when Boston changed from a bustling, chaotic, industrial 19th century city and entered the 20th century. It was a period when the strong mayor form of government and professional city planners came into being which would do so much to shape Boston after the Second World War. Seeds were sown between 1909 and 1913 by a pioneering - if paternalistic - effort of a large group of Boston business leaders to transform the way the modern City of Boston was governed, planned and developed.

Called the “Boston 1915 Movement,” it was largely the vision of Edward Filene, the moving force behind the Boston Dwelling House Company. Filene and four others formed an Executive Committee early in 1909 to address the needs of Boston in the new automobile age. These men were James Jackson Storrow, Louis D. Brandeis, Bernard Rothwell and George S. Smith. Filene, one of Boston’s most important retail merchants, was concerned with housing for the working classes. Storrow was an attorney who specialized in corporate law and managed investment trusts. He later went on to restructure and save the General Motors Corporation. Brandeis was an attorney whom President Woodrow Wilson would nominate as the first Jew on the Supreme Court. Rothwell was President of the Boston Chamber of Commerce. Smith was a wholesale clothing merchant and President of the Boston Merchants Association.

Filene and his colleagues held a dinner for 230 of Boston’s business, industrial, financial , educational. religious and political leaders on March 30, 1909 at the Boston City Club on Ashburton Place. The dinner was the unveiling of the Boston Plan; “a far reaching plan” wrote the Boston Herald the next day. “for making the Boston of 1915 the finest in the world.

Fifty years later, in 1960, Mayor John Collins and his recently appointed Director of the new Boston Redevelopment Authority would present another “New Boston Plan”. That Plan was created in a Boston in despair and near bankruptcy; its tax base eroded by industry migrating to regions with lower wage scales and a vanishing middle class taking Eisenhower’s expressways to the suburbs. The first “New Boston Plan” - on the other hand - was announced in a time and spirit of great optimism at the dawn of a new century. Indeed, it was a celebration of the end of the 19th century. The unplanned industrial and transportation growth and overcrowded, unregulated and unsanitary housing conditions were choking the little old Boston of the post-Civil War period. Unchecked and uncoordinated capitalism was threatening to weaken industrial and business growth. The business community intended, through the Boston 1915 Movement, to put its own house in order and create an efficient and planned 20th century Boston in its own image within five years.

“In the headquarters which will be opened tomorrow morning at 20 Beacon Street we will call to our aid experts and all the other help needed. [We will] bring to Boston, in addition to what we already have here, a knowledge of all the best things that have been done by any other city in the world and combine all these best things in a Boston Plan.”

Some of the points included; as reported in both the Boston Globe and Boston Herald the next day, were:

by 1910: to have an expert accounting of the financial condition and resources of the city present and prospective, to understand clearly the waste in public resources and services, to have made a careful accounting of the human resources of the city to include the skill level of the workers and the executive abilities of industrial leaders, to create better working conditions, to extend existing industries and introduce new enterprises and to provide a comprehensive system of wage earner insurance and old age pensions.

by 1912: to have more music in the parks.

by 1915: to have a system of public education that actually prepares the boys and girls of Boston for their life work, to have well advanced the execution of an intelligent system of transportation for the whole state including electric, express, freight and passenger services, to increase the number of branches of the public library, and to have the best possible public health department.

Other speakers made additional recommendations for the new Boston of 1915. “We ought to move all our public schools to the borders of our city parks. There is no better way in which we can get our children the benefits of the country … good pure air and proper outdoor play.”

Another floor comment raised one of the most important issues of the Boston 1915 Movement, and one that led directly to the creation of Woodbourne; that of stricter building codes. “We need to compel builders to allow a decent amount of light and air in tenements.”

But it was the statement of Mr. George W. Codman that admitted the real meaning behind the Boston 1915 Movement. “Have we not misconceived the true nature of our corporate city life? We have tried to run the city as a political institution and have made a dismal failure at it. We think now that we want a business administration of our cities with businessmen in command.”

And that was exactly what was attempted in the 1909 mayoral election when James J. Storrow, executive committee member of Boston 1915, ran against John F. Fitzgerald, who was seeking his second term in office.

Before (and after) Boston 1915 there was the Good Government Association, and both were made up of the same people: The Associated Board of Trade, the Chamber of Commerce, the Merchants Association and the Boston Bar Association. The Good Government Association (GGA) was created in 1903 by Louis D. Brandeis and other business leaders. Its first president was Lawrence Minot, son of William Minot Jr. who lived at Woodbourne. (Lawrence Minot, as chief executor of his father’s estate, would sell the property to the Boston Dwelling House Company.) The GGA was formed mainly in response to the conviction of State Representative James Michael Curley for fraud in Federal court because he took a civil service exam impersonating a constituent in 1902. This was the final blow for business leaders who had watched in horror at the political rise of the Irish Democratic ward leaders and their art of patronage. Curley was anathema to the business leaders of the GGA; he represented all that was going wrong in elected city government. City affairs, in the eyes of these men, were being directed from Irish Democratic clubhouses in the North End and from Curley’s base in Ward 17 in Roxbury. City agencies were being filled with often incompetent political appointments. What was worse was the increased taxes levied on business property due to the soaring costs of municipal contracts - particularly in construction - because of graft and kickbacks. All this caused the GGA to form and seek ways to correct these problems before commerce and industry moved out of the city. In this context it is easy to understand why a municipal financial audit and a study of waste and mismanagement in City affairs were the first two points of the Boston 1915 agenda.

The election in 1905 of John F. Fitzgerald (grandfather of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy), political boss of the heavily Irish Catholic Democratic North End, created panic within the GGA. In 1906, they lobbied through the press for an investigation into corruption in the awards of city construction contracts, for which they held the Mayor personally responsible. Mayor Fitzgerald - hoping to avoid an investigation damaging to his reputation and political ambitions - called for an independent Finance Commission to review city expenditures. This was authorized by the Republican controlled State Legislature in July of 1907. Yet, although the Mayor appointed the seven member Finance Commission (including the progressive former Mayor Nathan Matthews, who had always worked well with Irish political leaders), the negative press caused by the investigation into illegal contracts cost him reelection that year.

The Finance Commission (or FinCom) realized that reforms had failed in the past because the structure of government remained in the hands of ward leaders whose power rested with patronage and often graft. The FinCom also felt that the present form of ward-based city government was pushing property taxes too high because it depended upon increased city spending on municipal jobs and job generating capital projects in the wards. The FinCom felt that this was weakening the industrial and commercial base of the city. During the first six months of Boston 1915, the FinCom devised a new City Charter that would be brought before the voters in November 1909. With the strong backing of Boston 1915 Executive Committee member, Bernard Rothwell, acting in his capacity as President of the Boston Chamber of Commerce, the FinCom introduced a strong Mayor charter in order to dilute the locally based (and Irish controlled) city government. The Board of Aldermen and Common Council would be abolished and replaced by a nine-member City Council elected at large, citywide. The powers of mayor would be strengthened and the term of office extended to four years. (The new Charter, wrote James M. Curley in his 1957 memoirs, “was apparently designed to get rid of me.” Just the opposite was true, however, as Curley took full advantage of the increased powers of the mayor during his four terms in that office.)

Voters approved the new charter in November of 1909 by 52%. Ironically, although the businessmen reformers won control of a weakened City Council, they lost control of the Mayor’s office. In a hotly contested race, which can only be described as a class and ethnic contest, the wealthy Storrow lost to ward boss Fitzgerald in January 1910. More people voted than in any other election for mayor. Fitzgerald would be the first Mayor of Boston to serve for four years.

John F. Fitzgerald saw his victory over James Storrow as a vindication of his good name. (Decades later, his daughter Rose would equate the 1910 campaign with the one that her son John waged against Richard Nixon for the Presidency.) In the words of Doris Kearns Goodwin, “the Mayor was more secure in his knowledge that he was indeed equal to the task of governing his city … a task, ironically, made easier in his second term as a consequence of the reform legislation he so vigorously opposed. By providing limits to the frenzied patronage seeking which undermined his first term, the new city Charter protected Fitzgerald from his own vulnerabilities …”

The second Fitzgerald administration worked in harmony with many of the goals of Boston 1915. His campaign slogan of 1905, “a Bigger, Better, Busier Boston ” fit in perfectly with the optimistic times of the second term. Business leaders would profit from a bigger and busier Boston, especially now that the ward boss system had been weakened by the 1909 charter reform law.

“Fitzgerald made it clear,” wrote Goodwin, “that he intended to be judged his second term by one standard alone, his ability to advocate and enact legislation that would make the life of the average citizen more worth living; measures that would improve the moral and physical welfare of the people of Boston …” Words like ‘moral’ and ‘physical welfare’ were taken right out of the language so often heard from the Boston 1915 Movement. The By-laws of Boston 1915 stated, for example, that it was organized “for the progress of Greater Boston; to promote by all lawful means the social, material, moral and intellectual welfare of Greater Boston.”

Within the first six months of his second term, Fitzgerald took an action that encouraged the Boston 1915 reformers: he called for a monthly conference of all City Departments so as to coordinate city services as well as to clarify the responsibilities of each department. In the fall of 1910, the Mayor appointed Louis Rourke, who had previously served as Chief Engineer on a section of the Panama Canal project, to the new and consolidated office of Board of Public Works. The new Board combined the Street, Water and Engineering Departments into one agency under one Commissioner. This was a “decided first step in municipal efficiency and economy,” cheered the magazine “New Boston.” It observed that: “harmony of action is absolutely essential if the public work of a city is to be properly prosecuted.”

The Mayor, however, vetoed a City Council ordinance passed in late 1910 that would consolidate the Departments of Parks, Public Baths and Music into one Parks and Recreation Department. This didn’t go far enough for the Mayor; he wanted to reorganize the entire system of recreation services for city residents. The Boston 1915 Movement had an apostle in John F. Fitzgerald. Like his predecessor, Hugh O’Brien, the first Irish Mayor of Boston, Fitzgerald could work with the business leaders of Boston.

Soon after the founding dinner, the Directorate of Boston 1915 was expanded to include two members who would become trustees of the Boston Dwelling House Company (BDHCo), the banker Frank Day and the housing social worker Robert A. Woods. Three other trustees of BDHCo were among those invited to the founding dinner of Boston 1915, John Wells Farley, Charles H. Jones and James L. Richards. Richards, Director of Boston Consolidated Gas Company, was one of the Filene Seven who initially organized the movement. In the spring of 1910, William A. Leahy was added to the Executive Committee as a representative of the Mayor.

The Board of Directors numbered eighty men and women and included Robert Treat Paine, the dean of philanthropists in Boston who developed the housing for working men in Jamaica Plain’s factory district, (Paine died on August 11, 1910, so his participation in Woodbourne can only be speculated,) architect Ralph Adams Cram, and the daughter of the Irish patriot and editor of The Pilot, John Boyle O’Reilly. Mary Boyle O’Reilly was involved with prison reform and served on the City Board of Children’s Institutions. Other Boston 1915 Board members were Phillip Cabot of The Improved Housing Association, Ellen Coolidge, of the Boston Social Union, Meyer Bloomfield also of the Boston Social Union as well as the Civic Service House, James H. Fahey, publisher of the Republican Boston Herald and a Director of the Boston Chamber of Commerce, and the Reverend John Hopkins Dennison of the Central Congregational Church on Newbury Street. The Catholic Charities was represented by its Director, the Right Reverend Joseph G. Anderson, the Auxiliary Bishop of Boston and Reverend Maurice J.O’ Connor.

The “single aim of the Boston 1915 Plan,” as stated in New Boston magazine, the official organ of the movement, was “to apply the principles of business organization to a federation of agencies, to focus this combined effort by setting definite goals for early achievement.”

It was the intention of the Directorate from the start to promote the aims of Boston 1915 through a widely advertised public program that would show what civic cooperation meant. It was called the “1915 Boston Exposition: a graphic display of the living and working city … a display of Boston as a going concern.” The term ‘Exposition’ was deliberately chosen because it was inspired by the World’s Columbian Exposition (Chicago World’s Fair) held in Chicago from May through October 1893. Indeed, the entire agenda of Boston 1915 was under the enormous influence of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. It is difficult to imagine now, the magic that the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair cast over American cities for the first quarter of the 20th century.

The Chicago World’s Fair was built over 686 acres of lakeshore parkland to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the discovery of the New World for Spain by Christopher Columbus. The fairgrounds were landscaped by Frederick Law Olmsted and the exposition halls - some of which were huge - were designed by the greatest living architects and artists of the day. The fair achieved almost universal acclaim because in the midst of the disorganized industrial city which sprawled over miles of congested if not squalid housing, serpentine transportation networks, and inept if not corrupt political machines in city halls, was a planned metropolis of wide boulevards, parks and waterfronts; spacious and handsome buildings of uniform massing and proportion, and an efficient transportation system. It was called “the City Beautiful” and Boston’s Woodbourne section was a result of the concepts first introduced in Chicago to create a beautiful orderly city. The Chicago World’s Fair was the triumph of the city planner; indeed the fair would make that new term a recognized force in the development of the 20th century city. The fair was also the triumph of private investors and business leaders who largely financed and managed the Exposition. (The fair was directed from an elegant, domed Administration Building in the center of the complex). This fact was not lost on the reformers who saw the Chicago World’s Fair as a model for the future of American cities: a planned, rational, coordinated city, uniform in scale and design and directed from a central office; not by political machines but by business leaders. (The fact that the fair barely made $400,000 in profit from an investment of $28 million was not lost on planners. As the Woodbourne Directors would learn, philanthropy does not make money.)

All the buildings at the Exposition were spray painted white which increased the sense of a unified whole over the vast campus of huge buildings, while giving it a celestial, futuristic glow which did not fail to impress fairgoers with a vision of the city of the future. The beauty and efficiency of the fair’s White City was in marked contrast to the dull brick and polychrome stone gothic buildings of contemporary cities and the barking disorder of urban life. (When the four Woodbourne community apartment buildings on Hyde Park Avenue were completed, their light color stucco walls caused the area to be called “White City” because they were the only buildings southwest of the Boston Elevated Terminal at Forest Hills. The name still lingers today, but it had far more meaning in 1914.)

The Boston 1915 Exposition opened to the public on November 2, 1909 at the old Museum of Fine Arts in Copley Square. This building was just the sort of fussy polychrome stone and brick pile of applied ornament to which the White City was in contrast. (It would be razed about a year later for the present Copley Plaza Hotel, completed in 1912). The new Museum of Fine Arts opened that same month. This elegant temple of art built on clean, classic ‘City Beautiful’ lines was just the sort of future that the World’s Colombian Exposition promised. Built of light grey granite, it overlooked the tamed, landscaped swamp rechristened by F.L. Olmsted as the Back Bay Fens.

The Boston Herald called the Boston Exposition, “not as much a show as an awakening … hung on the wall where the Valasquez painting once hung is the ‘gist of it’,” - a banner outlining the platform of Boston 1915. “It is possible for the willing worker, on an average wage, to bring up his family amid healthful and comfortable surroundings. That they may become useful citizens … Boston 1915 is a ‘City Movement.’ It requires cooperation of all people and organizations for the improvement of Boston. It is a City Plan, which will put all plans into one general program. It is a City Exposition, showing year by year, the city’s progress in its factories, stores, public departments, homes and health.”

Over two hundred exhibits were broken down into three main themes: The Visible City, Educational, and Social and Economic. City planning, parks, streets and boulevards, and housing were among the exhibits in the Visible City area of the exposition. “One of the most interesting exhibits,” wrote the Boston Herald on November 2, 1909, “is the contrast, actual size, between a model tenement and an actual 3 bedroom tenement in Boston’s North End.” Also included were extensive models and plans for houses of workingmen in England and the United States. This exhibit would have a direct and immediate influence on the design and construction of the first phase of Woodbourne.

Other models were the City of Boston “with every building and street correct” and a $75,000 exhibit of that holy land of the City Beautiful, Chicago.

There was also, as the Herald noted, “much in the exposition that was spectacle; the Curtiss aeroplane, models of the Wright Brothers aeroplane and wonderful scientific moving pictures, not to mention Italian marionettes. The 1893 World’s Fair had 14 acres of sideshows and spectacles too.”

A key exhibit for Edward Filene was “The Catholic Church and Institutions” in a portion of the hall devoted to organized religion in Boston. Filene recognized that the Catholic Church was on the verge of being a major political as well as social force in Boston because of the population growth of the Irish and, most recently, the Italian communities. The Irish Catholic was no longer a subordinate minority and if Boston 1915 was to succeed it needed the support and the participation of the new Archbishop of Boston, William Henry O’Connell.

On September 30, 1909, Filene wrote to Archbishop O’Connell regarding the enlargement of the Board of Directors of Boston 1915. He requested a meeting to discuss “the inception, development and purposes of the Boston 1915 Movement.” O’Connell agreed to meet with Filene on Sunday evening October 3, 1909. At that meeting, the Archbishop delegated Reverends O’Connor and Anderson to help organize the exposition exhibit on the Catholic Church and its schools. But O’Connell himself was conspicuously absent (as the press noted) from the special opening night attended by 4000 people on Saturday evening, October 30,1909.

William Henry O’Connell became Archbishop on August 30, 1907 at the death of Boston’s first Archbishop, John J. Williams. It was an auspicious time for Boston Catholics, which O’Connell recognized and exploited completely. He was not the accomodationist like the gentleman Reverend Williams; he didn’t have to be. The Irish Catholic was in the majority now. O’Connell’s governing ideology was made perfectly clear on October 28,1908 at the celebration of the centennial of the founding of the Catholic Diocese of Boston. Standing at the pulpit in the Cathedral of the Holy Cross, a building far bigger than City Hall and taller than the State House, O’Connell declared the new order in carefully chosen words. “The Puritan has passed; the Catholic remains. The child of the immigrant is called to fill the place that the Puritan has left.” To the sons of the Puritans of Boston 1915 the message should have been crystal clear, “The Catholic is here. You must deal with him on his terms.” Clearly inferred was the deeper message, “The Irish are here.” After a century of discrimination against Irish Catholics at the hands of Protestants, O’Connell would have very little to do in cooperating with them unless it was on his terms; on terms suitable to Catholics. He demonstrated this time and again as he ran the Archdiocese with a strong hand until his death in 1944.

The Jewish merchant, Edward Filene, himself no stranger to ethnic and religious discrimination, believed in the cooperative spirit of Boston 1915 and he was determined to reach out and include the Catholic Church. He was also pragmatic; Irish Catholics were now a majority political bloc and they listened to the Archbishop. The success of Boston 1915 depended on a broad base of public support.

On December 3, 1909, Filene wrote to Archbishop O’Connell that the Exposition highlighted the serious need for better housing. In this letter, Filene set the groundwork for Woodbourne. “Among such problems [facing the City].” he wrote, “that of housing seems to be the most serious and pressing. Promiscuous crowding under depressing conditions of those least well armed to resist evil creates a moral issue difficult to deal with. Getting together the religious institutions for us [that is the Boston 1915 Movement] would be desirable for dealing with the housing problem. I think it practically and reasonably possible that as much as $200,000 can be raised as a beginning for better housing. With that sum, new cooperative housing plans can be drawn up.”

The Archbishop replied promptly on December 5, 1909 that he would participate on his terms. “The plan you propose for the betterment of housing of the poorer people of Boston appeals to me very strongly. If I am to go into this movement personally it must be that I shall be at the head of it, for reasons you must understand.”

The record does not explain those reasons but it was clearly a test to see how far the business investors - willing to put up $200,000 - were willing to go for the Archbishop’s prestige and participation. Apparently, they would not go that far; even to prove that the venture was in the spirit of reform and the public good. But Filene kept trying. “The glory of the church,” he wrote Archbishop O’Connell on January 20,1910 “has always been in her curative and redemptive work . . bad morals are caused by overcrowding in tenement districts. I am more than ever convinced that it lies in your power to inaugurate a work to remedy those conditions. It is here that the churches undertake, as a part of their religious work, the forming and carrying out of some plan by which the people of Boston will have better housing.”

When on November 1, 1911 the Boston Dwelling House Co. Directors signed the deed of trust to create moderate-income housing, Archbishop O’Connell’s name was among them. But in a letter to the BDHCo Trustees from his private secretary, dated January 5, 1912, he made it clear on what terms he would participate: “the Archbishop has lent his name to the Boston Dwelling House project … but will not be able to attend any business outside his regular routine duties.”

On November 15, 1913, the Archbishop resigned from the Board of Trustees stating to Board President Henry Howard “I have not been able to attend the meetings nor give the matter the consideration and time it deserves.” By then, as will be seen; the Boston 1915 Movement had ended.

With or without Archbishop O’Connell (who was elevated to Cardinal in 1911), Boston 1915 steamed ahead. In May 1910, the magazine “New Boston” first appeared. It was the self-described “official organ of Boston 1915. A monthly record of progress in developing a greater and finer city.”

“New Boston” ran until the end of 1911. Each issue had articles on a wide variety of social issues, some of which are still relevant today. These topics written by experts in the field ranged from housing and transportation to a spirited campaign to “Save the Fourth” designed to ban dangerous fireworks. Articles such as the improvements to the Charles River basin, wholesome milk, the evils of billboards, the character of moving pictures, Boston’s garbage problem, public spirit and the tramp, schoolhouses as neighborhood centers, making wife desertion unpopular, Americanizing our immigrant children and “five essential ways the automobile has added to the wealth of the city ” show the very broad range of concerns the Boston 1915 Movement enveloped.

The Boston 1915 Directorate was divided into committees. One of the most important was the Housing Committee which first met on February 28, 1910. It was made up of Philip Cabot, E.T.Hartman, Meyer Bloomfield, Matthew Hale (City Councilor from 1910 to 1912), Charles Logue, J. Randolph Coolidge Jr., Richards Bradley, Warren Manning (a partner in the Olmsted firm), Henry G. Dunderdale, the architect William D. Austin (who designed the Jamaica Pond boathouse and bandstand in 1910) and the playground advocate and educator, Joseph Lee.

Their report, “The Boston House Problem,” was printed in the first issue of “New Boston” and focused on the conditions of dwellings in the North End, West End, Charlestown and South Boston.

The goal of the Housing Committee was to improve the overcrowding and sanitary conditions of the existing housing in these districts. No new Woodbourne-type subdivision was proposed for the North End. “Boston 1915,” the report recommended, “will organize a bureau whose duty it shall be to investigate housing complaints registered from any portion of the city.” In 1911, Boston 1915 supported a bill introduced by Mayor Fitzgerald that proposed to revise the current housing codes to apply to wooden 3 family houses. Boston 1915 proposed regulating what was understood by both business and government to be a private sector role. It was still the business of businessmen to provide housing.

Slum clearance would come 25 years later when the Federal government made housing a public priority in the face of the fact that the private sector could not provide it. The Boston Housing Authority was created in 1935 to provide, with Federal funds, housing for the wage earner.

The January 1911 issue of “New Boston” ran a story written by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. that illustrated the design goals of housing beyond the central city districts that would be the model for Woodbourne. This was Forest Hills Gardens in the borough of Queens, New York, financed by the Russell Sage Foundation and planned and landscaped by the junior Olmsted. The story was appropriately titled “a suburban town built on business principles.” The tenement districts could only be ameliorated with improved and enforced building and sanitary codes together with better public health services. The objective of the Boston 1915 Housing Committee was that these overcrowded and unplanned residential districts should not spread out along the newly opened rapid transit lines linking the downtown core with the suburbs of Roxbury, Dorchester and Jamaica Plain. The planned suburban development would be built in those suburbs and Olmsted Junior’s article on Forest Hills Gardens was held up as the ideal for those projects.

The second Boston 1915 Exposition had housing as its main theme. It was held November 10 to 22, 1910 at Tremont Temple and the Boston Arena. More of a conference than an exposition, the event was called “The Civic Advance Campaign”. The highlight was a dramatic pageant at the recently opened Boston Arena on St Botolph Street titled “From Cave Life to City Life.” The intention of the program was to draw public attention to the problem of city building and it was designed to show the development of homemaking. It was held on Thursday through Saturday, November 10 through 12, and had sections reenacting cave dwellers, the Indian village, the Colonial town and the bustling 19th century city. The Civic Advance Campaign opened with “Mayor’s Night” at Tremont Temple with Mayor Fitzgerald as the keynote speaker. The November 1910 issue of “New Boston” exclaimed that the fundamental meaning behind Boston 1915 and its second Exposition “is to help create [a] state of mind. There is no reason why a municipality cannot be planned and made beautiful except through indifference and bad habits. [The city’s] affairs should be conducted economically and in strict business principles, properly planned, decently ordered and economically administered.” To achieve this, “its citizens have to get into a [receptive] state of mind.”

The Tremont Temple conference outlined what would occupy the Boston 1915 Directorate in the coming year: it would write, influence and advocate a legislative agenda that would push forward, by force of law, the state of mind desired by the reformers.

Fifteen bills relative to police, education, housing codes, public health and city planning which the Directorate had approved for action were reviewed in the March 1911 issue of “New Boston.”

These comprised the 1911 Program for the Boston 1915 Directorate; some of which are still relevant 88 years later:

1. Establish a proper public authority to plan and provide for comprehensive development of the city.

2. Federate cities and towns into one Metropolitan District.

3. Organize larger uses of schoolhouses.

4. Create a civic center.

5. Establish more convenience stations and drinking fountains.

6. Provide better sidewalks (build 10 miles of paved sidewalk every year for 10 years.)

The most important Project of the 1911 Program for Boston 1915 was the first bill, House Number 1109, “To improve the conditions of the Metropolitan District.” The bill was “designed to provide Boston and the Metropolitan District with a city plan developed on sound moral, industrial and social lines.” It would create a 3-member Commission which “would study and make planning recommendations for better homes, structural and sanitary safety of buildings, prevention of congestion and fire hazards and provide for reservations of land for public use.”

Boston 1915 put all of its great prestige and energy behind passage of the bill, which was largely the work of the Boston Chamber of Commerce. The Chamber’s 1911 Report, “Real Boston: The Get Together Spirit Among Cities and Towns,” stated the case to the legislature, the public and the press of the Metropolitan District. It said that Boston was actually part of a city made up of 40 cities and towns stretching from Salem to Cohasset and westerly to Framingham. The Chamber and the Directorate of Boston 1915 introduced the “Real Boston” bill that would create the “Federation of Metropolitan Boston.” In the April 1911 “New Boston,” March G. Bennett, Chair of the Real Boston Committee wrote what a Federation could do for metropolitan Boston; he argued that a federation already existed in sewer, water supply and parks. In language predicting the rise, decades later, of the Mass. Turnpike Authority, MassPort and the MBTA, he stated that cooperative action would be valuable for transportation facilities, industrial education, factory development, dock facilities, industrial railways, direct highways and uniform building laws.

The Chamber staffed the 10 person Real Boston Committee made up of men from Boston (the chair,) Brookline, Newton, Cambridge, Malden, Lexington and Somerville. This committee included Boston Dwelling House trustee Robert Woods and the influential journalist Sylvester Baxter. Baxter was a major champion of the Metropolitan Park Commission (today the MDC,) one of the first metropolitan governing agencies established in the Commonwealth. He was an ardent advocate of metropolitan planning and government.

The Directorate of Boston 1915 staked all their considerable influence and collective reputations on the passage of this legislation. The bill failed to pass out of committee in April 1911 and a different bill was refiled in May. It was strongly supported by Governor Eugene Foss who sent a message to the Legislature in April 1912 urging passage of the legislation. But it was defeated in the Metropolitan Affairs Committee later in the month. It was a mortal wound for the reformers. The heart and soul of Boston 1915 was that only through rational city planning could the 20th century city be realized. The Chamber and its allies in Boston 1915 stated that a plan for the City of Boston Plan could not be made and implemented without full cooperation of the surrounding cities and towns. City planning on a large and comprehensive scale would harmonize the physical city and reduce conflicts of purposes and waste of resources. When this goal disintegrated with the defeat of the “Real Boston” bill, the reformers lost energy and Boston 1915 collapsed within a year. The business reformers failed to understand the dread of annexation in the hearts of the cities and towns on the borders of Boston. Try as they might, the Real Boston Committee and their legislative allies could not overcome the fear that if cooperation began today, annexation would follow tomorrow.

(Writing at the end of his term, Mayor Fitzgerald stated that the Boston 1915 Movement was “a more altruistic and ambitious scheme than ever was undertaken in any American city. Although it has ceased as a tangible movement, its stimulus should be included in a list of causes for Boston’s progress during this period of four years.”)

Mayor Fitzgerald was a strong believer in the legislation. His speech before the 1910 Civic Advance conference was about the need for municipal planning. When the bill failed to pass, he blamed the towns of Newton and Brookline for their shortsightedness. But then he knew only too well that the ethnic immigrant power that he represented was the primary reason the suburbs rejected the Federation of Metropolitan Boston in the first place: they wanted no part of Boston’s tribal politics. (In that same legislative session also came, in the words of the Boston Herald, “the annual attack on the Boston Charter by the Democratic machine.” Senator Martin Lomasney, ward boss of the West End, had proposed a bill providing for a City Council of 28 members.)

But Boston 1915 was victorious because it brought city planning to Boston. In 1911, the Commonwealth created the Homestead Commission to develop a long range, comprehensive housing program that included site planning and housing design, of which Woodbourne was an early example. The 1913 Report of the Commission contained language very similar to that of the Boston Dwelling House Company proposal two years earlier: all families deserved a wholesome home and only by conscious design, direction and supervision within a planned development could the working man have the housing he needed for his family. The Commission recommended that each city and town over 10,00 people be required to have planning boards. After the defeat of the “Real Boston” bill, Mayor Fitzgerald petitioned the General Court to authorize the City to establish the Boston Planning Board, which was approved on January 27,1914.

Discouraged by their legislative defeat and tired of all the parochial politics, the tattered remains of the Boston 1915 Directorate could take no pleasure in the establishment of the Boston Planning Board because in January of 1914 James M. Curley began his first term as Mayor of Boston.

Although a very popular Mayor at the end of 1913, with strong support from reformers, the business community and the ward leaders, Fitzgerald at first declined to run for reelection. He planned instead to campaign for the United States Senate against Henry Cabot Lodge in 1916.

After Curley announced his candidacy for Mayor, both the ward leaders (for whom Curley never had any regard) and the reformers prevailed on Fitzgerald to run for a second term to keep Curley from winning. But Fitzgerald’s campaign was crushed and he resigned from the race in December 1914 amid allegations (gleefully exploited by Curley) of an affair with a cigarette girl and cabaret singer, Toodles Ryan.

Mayor John F. Fitzgerald built an administration of cooperation between the public and private sectors. Reformers could work in that municipal atmosphere. Curley, on the other hand, thrived on conflict and the war he waged over the next thirty years between Yankee and Irish, business and politics was not a place in which business leaders or reformers could flourish. Moreover the parks and beaches, schools and hospitals that Curley built during four terms as mayor and for which he is fondly remembered even to this day, were built on the ever increasing property taxes which had to be paid by business and property owners. (“The Republicans of our glorious Commonwealth,” wrote Curley in his 1957 memoirs, “should admit that improvements which advance the health, happiness and welfare of all people cost money. Is a low city debt and low tax rate the price we must pay for human suffering?”) But the happiness and welfare of James Michael Curley and his associates came first. These improvements were vastly over budgeted because of political corruption. Contractors who wanted lucrative city public works projects had to pay the Mayor first. Nothing symbolized this better than the construction of Mayor Curley’s grand mansion on the Jamaicaway during his first year in office. So scandalous was the open graft, that in 1915 business leaders forced a recall election ( as authorized by the 1909 charter ) that Curley barely survived. But survive he did.

Amidst all this turmoil, the business community simply retreated for forty years. They would not reemerge until the middle 1950’s during the more benign administration of Mayor John B. Hynes. But the optimism had vanished then; Boston was in dire fiscal straights and Hynes needed all the help he could get. (Running against Curley in 1949, Hynes’ campaign slogan was “The New Boston.”)

Politics and planning have always been linked but never mix well. This was especially true during the thirty years of Curley’s rule over Boston government. He was Mayor from 1914 to 1917; 1922 to 1925; 1930 to 1933; Governor from 1934 to 1936; and Mayor again from 1946 to 1949. These years of conflict within Boston’s political life dashed the spirit of optimistic reform that created and motivated the Boston 1915 Movement and gave birth to the Boston Dwelling House Company.

The reform spirit that originally guided the efforts of BDHCo was gone when construction resumed on the second phase of Woodbourne coincidentally with the start of Curley’s second term as Mayor. (He replaced the choice of the business community, Andrew J. Peters, son of the owner of the Hosford and William’s subdivision adjacent to the Minot estate).

The second phase was dramatically different from the first two years of construction; not only in architectural styles, but also in ideology. In the first phase the architecture fit the ideology. The architectural style of the second phase changed because the reform spirit was replaced by profit and nostalgia.

The great optimism of the years before World War One, in which reformers, such as Boston 1915, sought to reshape American society along the lines of their own material and social values, was replaced by pessimism fed by the disillusion of the messy peace that concluded the War to End all Wars. Moreover, the change from war to peace was sudden and violent. The years 1919 through early 1921 were marked by labor troubles (the great steel and coal strikes and the walkout of Boston Policemen in 1919); the severe recession that struck in October of 1919 which left 5 million men jobless in 1920; and the emergence for the first time in American culture and politics of anti - communism in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution of October, 1917. (The American Communist Party was formed in 1919.)

With the return of Republican control of the White House in 1920 with Presidents Warren Harding; and after his death in office, Calvin Coolidge, federal policies were introduced which greatly increased prosperity. The revolt of the 1920’s was that against the reform ethos of President Woodrow Wilson which was crushed beneath the wave of the new profit culture and the dawning of the consumer era ushered in by Harding and Coolidge. The will for collective action against society’s ills lessened with the prosperous Roaring Twenties. American business life looked very good indeed. There was nothing to reform. Moreover a new cult of individualism was growing too. The right of the individual to profit and enjoy himself replaced moral and ethical improvement, the ideology of the Boston Dwelling House Company. Consequently, the tribal property of the 1912 Pope plan for Woodbourne was hopelessly out of date by 1920 and thus not duplicated in the second phase of its development. In the words of H. L. Mencken, “Doing good [was] in bad taste.”

Massachusetts was also swept up in 1920 with the historical nostalgia of the 300th anniversary of the landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth. The building styles of the 17th century were rediscovered by architects and the Colonial Revival style - the gambrel roof and especially the 17th century saltbox house - was in high vogue in the second phase of Woodbourne. Nostalgia replaced reform after 1922. It also fit the nationalism of the day; America was big and strong after the War. Colonial Revival was a pure American style. Forget the fact that British colonists brought it over to New England in the first place; it did not look as ‘imported’ as the Kilham and Hopkins Arts and Crafts designs imported from England for the first phase of Woodbourne.

But more than anything else, it was a different world for the investors of the Boston Dwelling House Company in 1920. Reform and business did not mix. The business of Boston real estate was business; not housing reform.

Richard Heath

February 23, 1998

Appendix