Oral History: Alice, Patty, and Carole Lieber

Alice (Barro) Lieber on her 100th birthday

Jenny Nathans interviewed Alice (Barro) Lieber and her daughters, Carole and Patty Lieber, on January 3rd and 13th, 2026 at Alice and Patty’s homes on Pond Street. The following is an oral history about Alice, who will turn 101 years old in June 2026, and her family, including their experiences living in France during WWII and their memories of living in Jamaica Plain since 1957.

What is your full name?

Alice: Alice Lucie Lieber. Well, it’s actually Barro, but it’s Lieber because I married. I divorced [my children’s] father (Edward John Lieber).

When and where were you born?

Alice: [I was born] in Belgium, the 10th of June 1925 - in Ghent, Belgium.

Patty: My grandmother happened to be in Belgium when my mother was born. My mother was not supposed to be born in Belgium. My grandmother was a professional ballerina. She planned to dance her last performance in Belgium and then return to Paris to give birth, but mom had other ideas. According to my grandmother, she had danced, and my mother was born the next day.

Do you have siblings?

Alice: No, [I was an only child]

Alice as a child

What were your parents’ names?

Patty: Her dad was Prosper Barro. He was born in Mechelen (also known as Malines), Belgium. And her mom was Renee Alice Scott. She was born in Calais, France.

Alice: My mother was a ballerina. She was very pretty, very cute. She danced [Russian-style] ballet.

Patty: [My grandmother] danced initially for the Belgian Opera and then for a French company. But she spent most of her time dancing in Northern Africa. She danced in classical ballets like Coppélia, The Sleeping Beauty, and Swan Lake. She was a kid when she started [dancing], in the States. Her family had come to the United States around 1910 as Mom’s grandfather, Albert, was recruited to be the director of several lace mills in Rhode Island and New Jersey. During WWI, the factories were taken over and became munitions factories, so the family eventually returned to France in the early 1920’s.

Alice: My father was living in the Belgian Congo, but he came back to Belgium. I don't know much about him, because he disappeared.

Patty: He abandoned the family. My grandmother was only 19 when she had my mother, which [was] scandalous [for the era], because at the time she wasn't married. Now it'd be like, “Yeah, so?” My mother said she never, ever felt ostracized or different because her parents were not married before she was born. Didn't matter; no one cared. Her father was living in the Belgian Congo when she was born, but returned to Belgium when she was seven. Her parents then got married and then he promptly abandoned them after a week and returned to the Belgian Congo.

Alice: I was seven years old when they married. My parents didn't get along. And really, mother didn't want to go with anybody. She didn’t want to go to Congo [with her child]. I had nothing to do with it. It was very bad for me. No father. When I was 20 years old, I met him again. I decided to meet him. I went to Belgium. He had returned to Belgium by that time and was working at the stock market. So, I asked for him, and he came. “Oh!,” he said, “You're my daughter?” I didn't look too much like him. He told me he wanted to repair what he did. He wanted to buy me an apartment, and he wanted me to go to art school. It didn't work. No, no, and he was living with a woman, anyway, and they had a daughter. The daughter died. Well, he died himself shortly after I met him. Promises, promises.

Where did you live in France?

Patty: Mom lived in Lille and Nancy as a child. She lived in Nointel, which is in Oisi, during the war. Then she lived in Provence in her early 20's then returned to Paris. She also lived in Asnieres from her late 20's until we came to U.S. in 1957.

Alice: We did travel a lot, and then I went back to France. My grandparents took care of me all the time. They had a big property with a lot of animals. I'm crazy about animals, I love them, I love that life. In Nointel, a nice town in northern France.

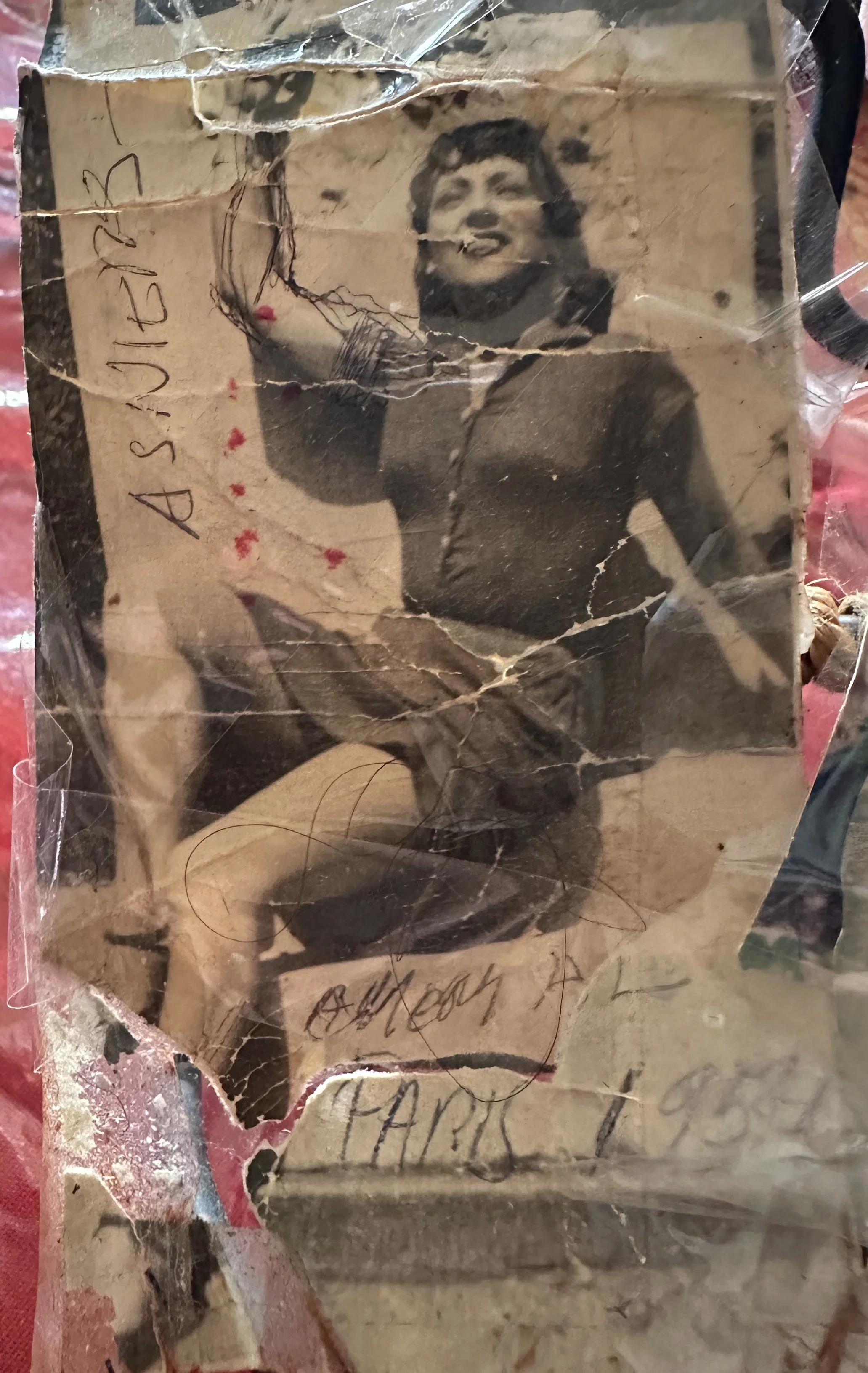

Alice in Paris, 1953

What are some of your memories of WWII in France?

Patty: Because of the war in Paris, [Mom] never finished high school. She couldn't - they blew up her school during the battle of France (She was 14 years old at the time).

Alice: I had two scholarships, one in arts and one in writing. I was 14. I had to wait until I was 16 to go to [arts] school.

Patty: And then the war came.

Alice: I was 15 when [the war] started. I was arrested by the Germans, because they did mistreat an old man. He was so tiny - an old old [Jewish] man. I got in a rage, and I went after the German, and I slapped him. They took me to the [General], and when I see the officer is putting his arm like this, and he had two big tears. I looked at the picture [the General was looking at] - It was me, his daughter, [we were] twins. She had just been killed. “Oh my God,” he said. “You look so much like my daughter.” I knew he was German, but then he released me.

Patty: Mom had heard later that [the General] had been killed because they felt that he was too sympathetic.

I heard Alice’s mother was in the French Resistance.

Patty: She sure was. When she had stopped dancing, she was living in both Paris and Brussels. She worked at the Chamber of Commerce, which put on fairs or exhibitions around Europe. She was like a general secretary. So, she was going back and forth between Brussels and Paris, while my mom had stayed in Paris with her grandparents. Shortly after the start of the war, she had a friend named Simone Pheter who worked at the Belgium Chamber of Commerce in Paris, where they were both working. [Simone] had said to my grandmother, “Since you go back and forth from Paris to Brussels, could you bring some papers back and forth for me, just some letters?” And my grandmother said, “Okay, I mean, we work together. You're a colleague. Yeah, I'm going to Brussels, anyways.” My grandmother had no idea initially that she was actually bringing forged documents.

My grandmother did this for a while, and then finally, my grandmother said [to Simone], “I really want to know, why do you have so many letters going back and forth to Belgium? And why can't you put the letters in the mail?” Simone finally told her what they were doing; they were falsifying passports for Jews. My grandmother said, “Well, I'm not doing this for you anymore as just a courier. I want to be involved and do the same thing.” So, my grandmother, who was in her early 30s, got very involved, going back and forth, back and forth. She was also forging documents at the Chamber of Commerce in Paris.

When my grandmother was finally turned in, she was living in Brussels. Thank God, she was back in Brussels in her apartment and there was not one document, not one shred that linked her to anybody in France. So, when the Nazis picked her up finally (because she was turned in by somebody in her building who was suspicious of her “activities”), they were beating her and asking her about her family. She said, “I'm an orphan. I have no family. I don't know my family. I've never had children. I know nobody.” She didn't have one lick of documentation to connect her to anybody; I really think that's why my mom and her family were safe, or they would have gone with my grandmother.

Alice's mother, Renee Alice Scott

My grandmother was initially in jail for six months. Then she went to Mauthausen concentration camp in Germany, and then she went to Ravensbrück [concentration camp], where she stayed for three and a half years. She was sentenced to death three times. How she escaped it, I don't know, but her initial friend, Simone Pheter (of the Red Orchestra), who got her involved, was beheaded by the Nazis (in Plötzensee prison in 1943).

The family left Paris to go to Nointel after they learned my grandmother had been taken by the Nazis. Although my grandmother always said the Nazis had no information about mom and her family, her family did not know this, so they left to be safer. They had no idea what happened to my grandmother but knew she had been arrested by the Nazis.

Because [my grandmother] had been a ballerina, [she had] tiny and nimble fingers; she was really tiny. The concentration camp prisoners were working in the Siemens factory. They were supposed to be making munitions, but my grandmother said they sabotaged more things than they made. They were breaking them and throwing them on the ground. You could get your fingers in and sort of twist things around, so they made it so that things wouldn't work. My grandmother said that that was her pleasure of knowing that they were doing something to sabotage. My grandmother never got reparations from the Siemens Company who were complicit in the war.

She was in Ravensbrük for three and a half years; her family had no idea where she was. They thought she was dead. [They] had no idea, no way to communicate. Part of the reason I think my grandmother survived is because she was a political prisoner, because we're not Jewish. My grandmother, until the day she died, when we asked her - she lived to be 99 years old – “Had you known what was going to happen, would you have done anything different?” She looked at us, and she said, “Are you kidding? You always have to do the right thing.” My grandmother was very, very religious, very Christian. She said, “This is what Jesus told me to do, and it's what I did. You have to, have to.”

Alice: I was very lucky not to be [sent to a] camp.

Patty: Mom, tell her about the parachutes, what you and your grandmother did with the parachutists in the woods.

Alice: The Germans used to shoot the French, British, and the Americans [parachuting out of planes]. Some fell and we feared they were dead. So, my grandmother and me, we went at night with a flashlight to see if we could find the bodies.

Patty: [Oisi] is where she and her grandmother went into the woods to try to find downed parachutists to render aid, as my great-grandmother was a nurse.

Carole: My mom used to always tell us about how they would go into the field at night and find the Allied pilots who had landed there. And I know she used to talk all the time about one person; his name was Bill Morris; they hid him in the barn. He pretended to be a deaf-mute, so that nobody was asking him questions, until he could get out to where he needed to rendezvous with the troops. My grandmother would talk about things that she had done for the resistance, hiding people in barrels and forging passports, and hiding lists behind portraits.

Alice: I did risk my life too. I was a kid. I had a friend whose uncle was a baker. She was living with her uncle. He made little cakes with messages inside. And then we, the two girls, Madou and me, my best friend, we met at night and gave the messages to somebody else. You heard about General LeClerc? So General LeClerc was the [other] uncle of my best friend, a young man. He took the messages, and the British came at night in a field, by plane, and took the messages. [The Germans] didn't get suspicious because what he baked was so good. The Germans came there to buy [pastries] every day. We fooled them, all right! But it was very risky.

My grandmother during the war, wouldn't let me touch an egg. Ration for everything. The Germans took everything. You went to the store, you couldn't buy a dozen of eggs, three at a time. “You don't touch that!” I didn't.

Patty: In 2005, I was visiting my grandmother, a few days before she died. She was a few days shy of 99 [years old]. She suddenly put up her middle finger and said [something to the effect of], "That is for Hitler. He tried to kill me, but I showed him." My grandmother was an incredibly polite person and other than saying "merde," I never heard her swear, so this was shocking. My grandmother made it clear that it was not the German people who committed the atrocities against her, but the Nazis. She always made sure that we understood the difference.

Alice, were you living with your grandparents after your mother was taken away? When did you reunite with your mother?

Alice: Yes [I was living with my grandparents]. [We reunited] at the end of the war, after she was liberated.

Patty: In 1945, my mom would have been 20 then. For five years they had no idea [where she was].

Alice: My grandmother became my mother. I called her my “Mama” all the time. And my grandfather, “Papa.”

Alice

Alice, Patty tells me you worked as an actress and a model?

Alice: Oh, yeah, I hated it. I was about 22. It was after the war.

Patty: She was an extra in movies [in Paris].

Alice: I forgot the name [of the movies]. [I was in a movie with] Errol Flynn. He was very nice. And [I was in a movie with] Vincent Price too. And they chose me! No, I didn't like, I didn't know the way they did things, and I would have had to go to bed with many of them.

Patty: To get better [roles]. Not Vincent Price or Errol Flynn, but for other people. My mom always said that to advance her career, the casting couch was alive and well, like it still is today.

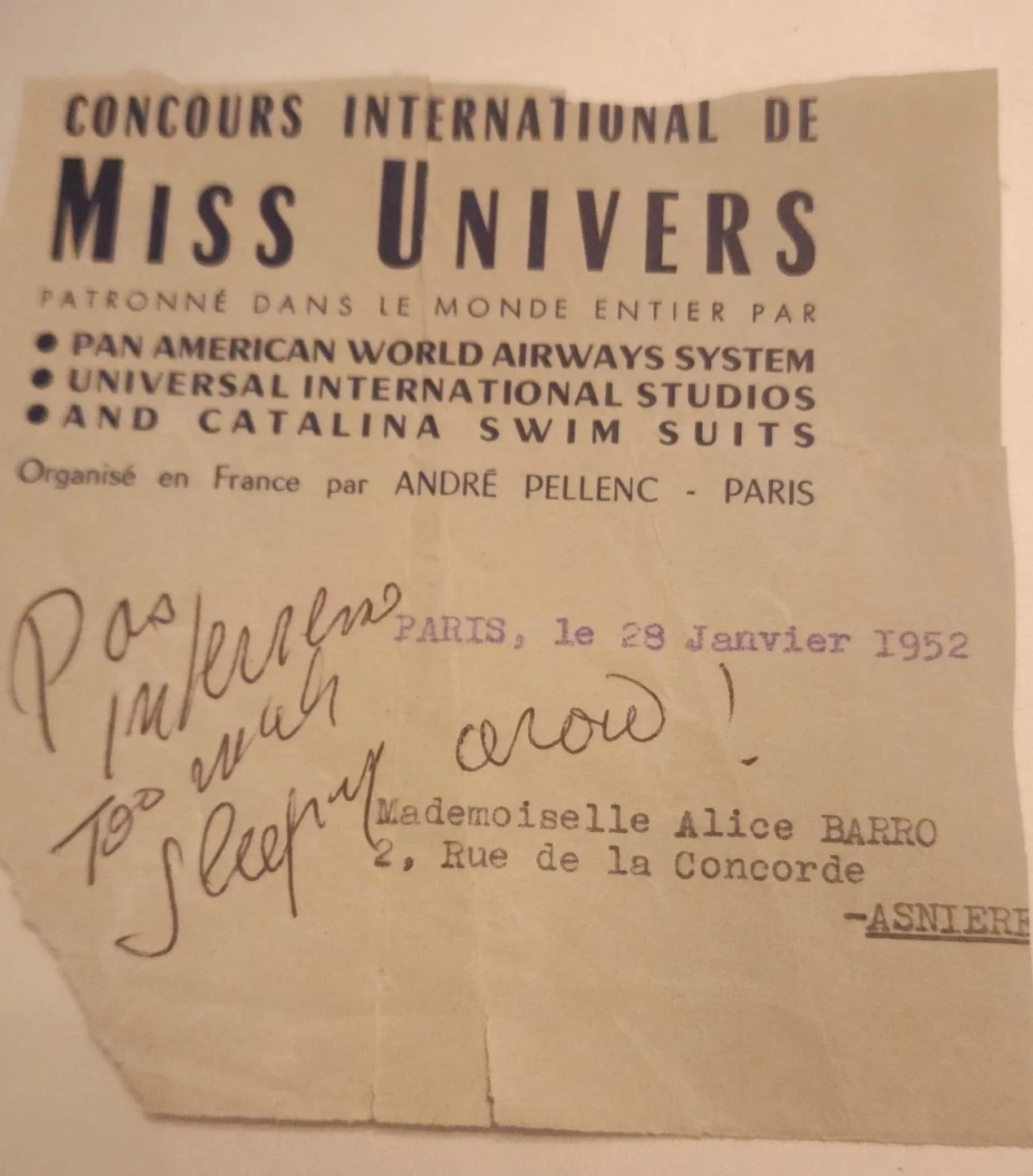

Carole: Mom was also asked to compete in the Miss Universe contest. She got an invitation in 1952 (the first event was in 1952). Mom declined as she did not like the idea of beauty pageants.

Alice's invitation to compete in Miss Universe, 1952

Alice, can you tell me about your ex-husband? How did you meet?

Alice: I fell in love with their father and we got married. I knew the relationship was bad, but I didn't realize it was that bad. What a life. I told him that I [would] come to the States with [him]. And then it got worse.

Patty: Mom married our dad in 1953 when she was 28. [My dad] was born in 1928 in Jamaica Plain and grew up on Chilcott Place, which was close to the brewery where his dad worked. [My parents met] at the SHAPE military headquarters. SHAPE stands for Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe. Mom worked for General Eisenhower.

Alice: I was working there. I was one of the phone operators for General Eisenhower. And I loved my job. [I worked there] maybe four years. My husband worked there in another area. He was a Sergeant. We met there and he was very pleasant. I didn't know he was a monster.

How many children do you have?

Alice: Three. Two daughters and a son.

Patty: My sister [Carole] and I were born in France. [We] were both born in the same place, in Neuilly Sur Seine, at the American Hospital, because our dad was in the US army when we were born. [Our] brother, Marc, was born [in Jamaica Plain] two months after we got to the United States.

When did you move to the United States?

Carole: We came to America in October 1957. I know from friends of my mother, who told me that when they first met me, I spoke French. I don't really have any recollection of really speaking English until preschool.

Alice: Because I was still married at the time, and I told Eddie, Ed, “This is your last chance. If you don't change, I want to go back to France.” He didn't change. I wanted to go back to France. The court didn't permit me to go. My son was born here, so I couldn't go. I could take the two girls, but not my son.

Patty: The court told mom during her divorce in 1960 that she could not take our brother out of the US as he was born in the United States. My sister and I, although born in Paris, came to the US on a US passport as our dad was in the US Army when we were born. I still have dual citizenship.

My brother was born two months [after we came to the States], and mom lived with her in-laws, my grandma and grandpa, on Chilcott place in Jamaica Plain. If you go down Chilcott Place, the biggest house on that street was their house when I was a little girl. It just was not a good situation for my mom, for many reasons. They split up when we were really little. And then my grandmother (the one who had been in the concentration camp) sold everything, left Belgium, and came to the United States to help my mother and help raise us when we were children.

Alice with her ex-husband, Edward Lieber

Where have you lived in Jamaica Plain?

Patty: Chilcott place when we came from France. Bromley Heath. Elliot Place. Lakeville Road. Spring Park Avenue, and then here, Pond Street. Mom's been here [on Pond Street] maybe 35 years, maybe longer.

Tell me about some of your experiences living at Bromley-Heath.

Patty: After my parents split up, we ended up in the Bromley-Heath projects. We lived there from 1959 to 1966. There weren't that many white families when we were there. It was, to me, a great childhood. None of us knew how poor we were till we got a lot older. But I never felt deprived because [there were] numerous single parent families, and everyone there helped each other. You could put that into perspective in the 60s; a lot of those women were single because their husband had been killed in World War II or Korea, or maybe they were divorced. There were lot of widows. The people there were wonderful. We grew up with Sidney Borum - my 4th grade boyfriend, and he has a health center named after him. And my sister's dear friend, Andrea Kelton, is an HR director at Harvard and the Hattie Kelton apartments are named after her mom.

Carole: And then we moved because my grandmother moved in with us. We moved to Eliot Place. My mom has only lived in Jamaica Plain in the States; she has never lived anywhere else. One thing that I think is important that gets overlooked is when we were living at [Bromley Heath] - it was before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 - and people got along, and people had friends of different races, different nationalities, different religions. We were all neighbors, and people were very neighborly. Nobody cared where you came from.

[When I was maybe six years old], there were these two elderly gentlemen who sat on a bench in front of our building every day; one was Black, one was white. One would talk about his father's experiences in the Civil War. And the Black man's family had come from slavery. I would go and spend time with them outside, every day. My mom would just look out the window and glance at me. She knew I was in safe hands. They would teach me little games like “eeny meeny miny moe,” and little songs.

Alice and her children at Bromley Heath

I remember on the weekends, as a little kid, all the teenagers would go down on the back steps of 265 Centre Street, and they'd be wearing pedal pushers and saddle shoes, and they'd have their roller skates. They put on their transistor radio, and everybody would be dancing. They were teenagers, and I just remember being a little kid thinking, “That's so cool. I can't wait to be a teenager.”

Carole: [After school] we would go down Centre Street, on the side where Stop and Shop is, and where the projects begin; the moms were all looking out the window, making sure all the kids, whoever's kids, got home safe. And that's where you could really get in a lot of trouble if kids started fights, because then by the time you get home, everybody knew.

Patty: We didn't have a phone for years. No one had a phone. You didn’t need a phone. All the moms were looking out for everybody. It was like a telegraph system. Anything you heard about was word of mouth. Living in that community, if you did something really naughty, and school was three blocks away, by the time you got home, you know damn well your mother knew about it, even if she wasn't there, somebody told her.

Carole: [When you did have a telephone], you could take your phone [number] with you. Our phone number was j-a-two, so Jamaica, two, which was 617-522.

Patty: My mom has had the same phone number since we lived in the projects.

Alice: Remember when I painted the wall [at Bromley-Heath]? The manager comes one day, “I want to see some things.” I said, “What did I do?” He said “That!” He loved it. I painted a sun, and different seasons. Nobody did that. I wasn’t allowed.

Patty: She painted a mural in our bedroom in the projects. You weren’t supposed to do that. She's like, “Well, I'm very artistic. I'd like to make a painting for my children.” Another memory of our time in Bromley Heath was that the Salvation Army sponsored some of the families to have a vacation at their facility, Camp Wonderland, which is still located in Sharon, Massachusetts. They sponsored entire families; we had cabins, all meals, activities, and transportation. For many of the kids, this was our first time really out of the city.

We were also recipients of Globe Santa. Our minister, Rev. Baker, from the Baptist church (now United Baptist, which is by the playground) wrote to them about us, and we all got gifts. We were also in Girl Scouts in the Neighborhood House. The Neighborhood House had lots of programs for kids and excursions, as well. We were poor financially, but our community provided us with what we needed.

Did you work when you moved to Jamaica Plain?

Alice: I had to work; I had no money. I worked at two nursing homes; one was awful, but at the Rogerson [House], it was wonderful. Those men were retired. They had a lot of money. They had their own bedroom, their car and everything. So, it was pleasant there. I was an assistant nurse. My director, she said, “Why don't you go and study to be a nurse? You would be wonderful.” One time, it was my schedule to work from 7 to 11, and then nobody came, so I had to stay there, and a man died on us. And we were only two girls there for that big place; give them meds, take care of them, do everything, and we were not supposed to do that - give the medicine, you know.

Patty: It was a retirement home at the time. Now it's a dementia facility, but at the time, it was a very upscale environment for retired men. There were retired judges. Most of them were bachelors or widowers.

Alice: I would have loved to work in a museum. I would have loved to reconstruct animals, like taxidermy. But I couldn't do it. I didn't have the time to do that. I went to work. And, you know, with three kids, I had other things to do. I [also] wanted to work for a vet. I didn't. [Instead], I gave my time for free. I did a lot of work with animals.

Patty: She did that at the veterinary clinic on Green Street (Jamaica Plain Animal Clinic). She used to volunteer there. She loved the animals. Amy Johnson ran the clinic [at the time]. My mom volunteered for years.

Alice, how did you get involved at the Jamaica Plain Animal Clinic?

Alice: I took my animals there. And then [Amy Johnson] said she was short on help. I said, “I can't do that, I don't have the knowledge.” She said, “I would teach you.” It started like this, a volunteer. I did assist her, even during surgery. She didn't pay me for that, but my [vet] bill was low. My grandmother, she took farmers’ animals. She didn't know anything about animals, but she was a war nurse. She did a lot at night. I studied from her. We love animals. How many did we pick up in a street, Patty? Our landlord didn’t say anything. Cats, dogs, whatever.

Patty: Back in the day, when we were kids growing up in JP, nobody took care of their pets. Animals would just run in the streets. People were not getting them spayed, neutered. They weren’t on leashes. So, we're forever bringing to my mother abandoned pets. I climbed up a tree once in a thunderstorm to get a cat; I was like 10.

Patty and Carole, did you have jobs or volunteer when you were young?

Patty: I was babysitting when I was 11. Then, when I got older, I used to work at [Southgate Pharmacy], which was on the corner of where CVS is, on Moraine Street. I worked there from 1970-1972. I used to work on the concession stand, and I also used to be a clerk. I remember having an argument with my boss one night because I found out that the boys made more money than I did because they washed the floor. They got $1 more an hour than I did. I told Mr. Mark, “I know how to wash the floor. I do it at my house all the time. I'd be happy to wash the floor to get an extra dollar.” So, I ended up washing the floor for the extra dollar. And I worked at Sparkle cleaners, which is now where the old Boomerangs was. There was also a cleaners here on the corner of Lakeville, where the Forbes building is. I worked there too.

Carole: I worked at the A&P (next door to Southgate Pharmacy), which is where CVS is now [at Moraine Street]. And I was a volunteer at Head Start. The Head Start program moved to the Children's Museum, and I volunteered there. And then I was a candy striper. My mom worked at a nursing home that was on Burroughs Street. I used to go there and volunteer with her. And my brother, he started working very young. He worked at the golf course in Brookline. He'd ride his bike over there. Our brother also delivered groceries for many years for McDonald’s Market, which was where the laundromat is across from the Forbes building.

Patty: I used to volunteer at the old Children's Museum on Burroughs Street. They had a program in the summer called July Jaunters, which was like a day camp for kids. But if you were a really good Jaunter, you could do volunteer work at the museum. We were in junior high, and you would take people around the museum and tell them about the different exhibits. That wouldn't happen today. I mean, we were kids 12, 13 [years old], and they were trusting us to do this with other visitors that were obviously paying to come to the museum. But we were so trained that some people said, “Wow, that 12-year old's really smart.”

Carole: I used to volunteer there also, but there were also great clubs there. There was a photography club [with] Mr. Tisdale. He would teach us how to use cameras, and then we would develop our photos in the dark room. And then my sister mentioned July Jaunters, and that was Miss Dickey. We'd go to the pond. We'd study amoebas under microscopes. We would pick up frogs. She'd have us wear feather headdresses, and we'd learn about the local Native Americans. I [also] remember taking sewing classes at the Eliot School when I was a kid.

I got involved in Kevin White's campaign when I was 14 years old. His office was right across the street. I was like, “I don't want this racist Louise Day Hicks becoming mayor of Boston. She doesn't want black children in the schools in South Boston.” I remember being over there, 14 years old, calling people, asking if they needed rides to the polls. It was just important to me, and a lot of that just came from how we were raised in a community, in a village, and the inspiration from my grandmother and my mother too.

What did you do in your free time?

Alice: We went to places, activities that I liked, [like] the library. We liked the zoo and the pond. I missed a lot of things in my life, that I could have done. It was very hard when they were little. But I wasn't bored. I loved my children, and I loved to pass my time with them; we went everywhere - walk, walk, walk, walk.

Patty: Oh my god, we walked a lot. We did art at home and visited Jamaica Pond and walked through the arboretum, ad infinitum, which is a beautiful blessing for those of us who live here. It's just such a beautiful outdoor space.

Alice: And the library and the museums. We didn’t buy many toys, but books, books, books. Lots of books. We always had books. I wanted [the kids] inside, not outside. So, they studied a lot. She's very artistic, that one (Patty). You made a lot of stuff.

Patty: Books were always a big, big thing in my house, because, when you don't have a whole lot of money, you got to think of things to do. I still read three to four books a week. Mom is over 100 and she reads a couple of books a week. She loves books. Tell her the kind of books you like best, Mom.

Alice: Murders and stuff like that.

Patty: Murder mysteries, that's what she loves.

Carole: I remember as a child going to Nantasket beach. And I remember my dad, when he would have visitations, taking us to Stoughton and saying, “We're going out to the country,” and complaining about the Sunday drivers - the people who only drive on Sundays, which is hysterical now. Everybody is so happy to get in their car to do anything [today]. Our dad used to take us pony riding. They used to have ponies up on Forest Hill Street. It was like a corral. But I think they had horses for older people. I remember seeing people on horses in Franklin Park. We'd go to the zoo. We'd go to [the beach at] City Point [in South Boston], because you could take the bus.

Patty: They used to have free swim at Curtis Hall. You had to wear the bathing suit they gave you. God knows how many people wore that bathing suit before you put it on your body. But we were kids, like nine or ten [years old]. All the kids had to line up on the sidewalk. And you went in the order of when you came. You went to swim for an hour; it cost a nickel. But if it was really super hot out, and you were really fast, you could get out of that ugly bathing suit, put on your clothes, and get back in the line to go for the next swim. I always made it at least twice.

One of my fondest memories as a real little kid, was [during Christmas time at] the Enchanted Village that is now at Jordan's Furniture store; it used to be in downtown Boston at the Macy's, Jordan Marsh. I remember that my mom and my grandmother would bring Carole, Marc, and I. We'd plan a trip for Christmas. We got our pictures with Santa. There used to be a store called Kresge’s, which was on the corner, I think of Bromfield Street, and they had a huge lunch counter. We'd eat lunch first, then go to Jordan Marsh and Santa. My mom and my grandmother must have been saving for months to be able to do that, to make a memory for the kids.

Carole: When we were older, we were all in the CYO (Catholic Youth Organizations) band. St. Thomas [Aquanis Church] had a CYO band, a very good band, award-winning. We used to practice marching in a huge parking lot across from St. Thomas Aquanis Church, where Farnsworth House is now. There were a lot of kids from the South Street projects who were in the band. [As] more of these people got older, and they weren't competing anymore for whatever reason, it morphed into a swing band. And then we became the official New England Patriots band. We used to go to the New England Patriots game Sunday and play. I played my little flute. You couldn't hear and nobody used to go because the Patriots were awful then. But those were fun memories. Al Tobias, he led the band, and he did a great job of it.

Renee Scott and her daughter, Alice Lieber, at the Hailer Pharmacy lunch counter, 1990

Were there any stores in Jamaica Plain that you liked to visit?

Alice: We didn't have much money. I made things with what I found. I made a lot of stuff. And I'm not ashamed to say that we found things on this sidewalk. Beautiful vases.

Patty: We used to go to Woolworths, which is where Morgan Memorial [Goodwill] is. [We would] at least have a lunch at the lunch counter. Woolworth’s had a lay away counter, and you could open an account with just 25 cents, so my brother, sister and I saved all our quarters and put thing on layaway year-round so we could have things for Christmas gifts. We always got mom Evening in Paris perfume, and our grandmother loved Jean Nate perfume. And next to Woolworth’s was the Store 24 building. Before it was Store 24, it was a grocery store, Publix market.

Mom, I know where you used to love to go with Meme – Hailer’s Drug Store, on the corner of Seaverns Ave, where Purple Cactus is. The guy who ran the store, Steve, must have had everything on earth you could imagine. No matter what random thing you wanted - his name was Steve Grossman - wonderful guy. You'd go in and say, “You know, Steve, I need knitting needles. I need a hacksaw. I need some socks. I need diapers, and I need some aspirin.” [And he would say], “Let me get it for you.” And they had the most amazing lunch counter. My mom and my grandmother would go there for years.

Carole: We also spent a lot of time at the thrift shop which was where ACE hardware is located. We got so many of our books there. We also liked to visit the fire station which was where JP Licks is, as we could watch the fire fighters going down the pole. We got by with what we had, but none of us had money. A lot of the kids we were in school with were in the same situation. They were new immigrants like us, or first-generation Americans, very diverse. But we all got along, and what we had in common was we were struggling, but nobody saw it as struggling. Nobody was feeling sorry for themselves.

(Left) Carole, Patty, and Alice Lieber, and Patty’s daughter, Jennifer O’Halloran. (Middle) Patty’s son, Daniel O’Halloran, and Alice. (Right) Carole, Patty, and Alice Lieber, City Councilor Benjamin Weber, and Marc Lieber

Patty and Carole, you mentioned that you had a family member that worked at the Haffenreffer Brewery?

Patty: [Our paternal] grandfather, Ernst Lieber, was born in the Alsace - Lorraine region of France, near Strasbourg. [He] was a brewer in Europe. He was invited to come to the United States in the early 1900s. He worked at the Haffenreffer plant as a brewer. He worked there for a long time, but my understanding is he had a very, very bad accident. He fell into one of the vats that was boiling, boiling hot. So, I remember as a little kid going to their house on Chilcott Place after he retired - he had burnt legs [and] my grandmother, his wife (Wanda), had to put [his legs] in a big empty plastic garbage can full of water to his knees to soak them. His accident happened maybe in the early 50s, late 40s.

Alice, how did you get to be 100 years old? What is your secret?

Alice: I walked a lot. I bicycled before that. We never had a washing machine. We never had anything like that.

Patty: We washed all the clothes in the tub. My mom never smoked, never did drugs, no way. Why don't you tell about your wine that keeps you young?

Alice: Yeah, that I like. I am French. I love wine.